About the Hocus Paintings

HOCUS is an acronym of the surnames of Saul Hofileña Jr., the intellectual author of the thought-provoking collection, and Guy Custodio who collaborated by painting Hofileña’s visions of Philippine colonial history. In the preface to the HOCUS III (Juicio Final) book Custodio wrote, “… I took instructions from Saul on how a painting should be done, the subject of each painting, the color schemes and all other matters that needed to be done, in order to transform paint and canvas or wood into a HOCUS painting.”

Each HOCUS painting is signed with an icon, Hofileña’s brainchild which he calls Anghel de Cuyacuy. The Filipino angel is seated on a bench, jiggling a leg nonchalantly (a typical Pinoy mannerism) while reading a book. He is an angel ready to battle ignorance and superstition, as well as Satan’s evil minions, according to Hofileña.

HOCUS enjoyed two hugely successful six-month exhibitions on April 18, 2017 to October 29, 2017 and September 15, 2019 to March 15, 2020. Six large paintings from HOCUS I are on permanent display at the East Wing Hallway Gallery at the 4th floor of the National Museum of Fine Arts which includes the thought provoking “La pesadilla” (The Nightmare). Also permanently exhibited along the Second Floor Northeast Hallway Gallery at the National Museum of Anthropology are five HOCUS paintings that were part of the Quadricula (HOCUS II) exhibition.

Gemma Cruz Araneta

Curator, Hocus I and Quadricula

HOCUS I

The Hofileña-Custodio paintings exhibited at the National Art Gallery of the National Museum of the Philippines on April 18, 2017 to October 29, 2017.

Lectores de las palabras perdidas (Readers of the Lost Words)

The Jesuit at the extreme right is reading a catechism. During the Spanish period, catechisms were printed with a syllabus to teach natives how to pronounce words, but not to understand them. Then as now, prayers were uttered repeatedly and solemnly without analyzing the meaning of the words intoned. Moving in single file, eyes bound with cloth, they blindly taught the faith.

An Augustinian “reads” a Tagalog novena, like the Dominican friar who holds a treasure box close to his chest. A Recollect “reads” a Visayan prayer book. It was in the Visayas, among other places, where they held sway. On the extreme left is a Franciscan “reading” a book written in Bicolano, the dialect of the territory that they controlled.

Lectores de las palabras perdidas

(Readers of the Lost Worlds)

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 6 feet

The Music of the Patronato

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

This HOCUS painting is filled with delirious details which explain the nature of the Patronato Real. The elegant organist with a white wig is the Spanish Governor-General playing the bamboo organ of Las Piflas, completed by Friar Diego Cera sometime in 1824. Aligned in the same row with the Governor-General are the members of the native principalia. One level up are the Christianized coastal dwellers, the Tagalogs, Ilocanos, Visayans, Kapampangans, along with the Mohammedans and Sangleys, infidels who resisted Christianization.

At the center is an indio with a crossbow, determined to climb his way up to the Crown which represents the King of Spain, “Patron of the Indies” by virtue of the Patronato Real. Like Sisyphus, the indio’s attempt to climb the socio-political ladder is condemned to never succeed. It is a hopeless task. To the right of the painting, a despondent indio hangs himself. Near the finial of the bamboo organ there are friars in the distinct robes of their orders, going about their merry business, at the summit of power yet never equal to nor higher than the Crown. That was the canticle of the Patronato Real.

The Music of the Patronato

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

Lucifer se ha rendido (Lucifer Has Surrendered)

Oil on wood, 5 feet x 4 feet

What if Lucifer repents? What will happen to our world when evil is finally vanquished by its own volition? Who or what will fill the void? At bottom left of this HOCUS painting, a crouched Lucifer abjectly receives the Sacrament of Confession after asking forgiveness for his sin of pride. Meanwhile, the serpent, which had entwined itself around a monstrance containing the Holy Eucharist, is releasing its mortal grip. Can the world continue existing without the eternal battle between Good and Evil? Didn’t God create all things material to test man’s free will, which is also His creation? Darkness against light, evil versus good. Opposites must clash perpetually, yet co-exist at all times. Vanquish one and the eternal dichotomy disappears. If Evil no longer exists, can good be of any use?

The faceless scribe writes that Lucifer has surrendered, we must now return to the void. Such is a logical conclusion since it is said that God created us to test us. Since the devil has returned to God’s sacred fold, there is no one to tempt and test our resolve.

Thus, return to the void is inevitable since there is no longer any use for God’s creations except to serve as a basis for a new one, with the proper rectification.

Go to the church of Loon, in Bohol, to find the answer written on its walls, but it is too late, the temple crumbled to dust during the earthquake of 2013. The Book of Genesis may shed some light, if it were not written in ancient Latin as shown in the Painting.

Lucifer se ha rendido

(Lucifer Has Surrendered)

Oil on wood, 5 feet x 4 feet

The Lost Island of San Juan

Oil on wood, 5 feet x 3 feet

Where was this lost island and why was it called San Juan?

The first map showing Isla San Juan was sketched in 1601 by Fray Herrera, one of the early

missionaries who came to evangelize us. Next, the island appeared in Dell Arcano del Mare made in Florence in 1646. An English fleet was said to have dropped anchor near the island in 1686, en route to Mindanao. The voyager, William Dampiere, described the Island of St. John as the only one not under Spanish rule: “This island is of good height, and is full of many small hills. The land at the southeast end, where I was ashore, is of a black fat mould; and the whole island seems to partake of the same fatness, by the vast number of large trees that it produced; for it looks all over like one great grove:’ Other French,

Dutch and Italian cartographers charted the island, sometimes off Surigao and near Dinagat, or near Siargao. Though it did not appear on Murillo Velarde’s landmark map of the Philippine archipelago, provincial officials in the area were still looking for it as late as 1940. In the 1960’s, interest had not waned: Historian and National Artist, Carlos Quirino deduced that San Juan Island is Siargao. For his part, Federico Aguilar-Alcuaz, National Artist for Graphic Arts, was determined to head an expedition to look for the lost San Juan Island, the Philippine Atlantis.

The Lost Island of San Juan

Oil on wood, 5 feet x 3 feet

Permanent Exhibit, National Museum of Fine Arts, Republic of the Philippines

Marcha del patronato (March of the Patronato)

Oil on wood, 5 feet x 3 feet

A mighty phalanx of angels, like Macedonian soldiers, descend upon these islands, waving banners bearing the names of conquered territories- Pampanga, Leyte, Nueva Caceres (Naga), Nueva Castilla (Luzon), Samar, Paragua (Palawan), Cebu, Panay, Bo-ol (Bohol), Ylo-ylo (Iloilo). The Sword and Cross-the formidable union of State and Church-conquered these islands.

Through the centuries, the sword weakened as the vestiges of the colonial State withered away, but not the Cross. To this day, throughout the archipelago, there are Roman Catholic churches, though battered and worn, their spiritual power remains intact.

The theologian Pseudo-Dionysus of Areopagite wrote in the sixth century “The Celestical Hierarchy”, wherein he divided angels into three hierarchies.

Angels called Seraphims, Cherubims, Thrones, Dominions, Virtues, Powers, Principalities, Archangels and angels which include guardian angels were each given a function in the heavenly hierarchy. This painting shows the Principalities, angels allegedly concerned with the welfare of nations and who belong to the third hierarchy of Pseudo-Dionysus’ categorization.

Marcha del patronato

(March of the Patronato)

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 6 feet

Permanent Exhibit, National Museum of Fine Arts, Republic of the Philippines

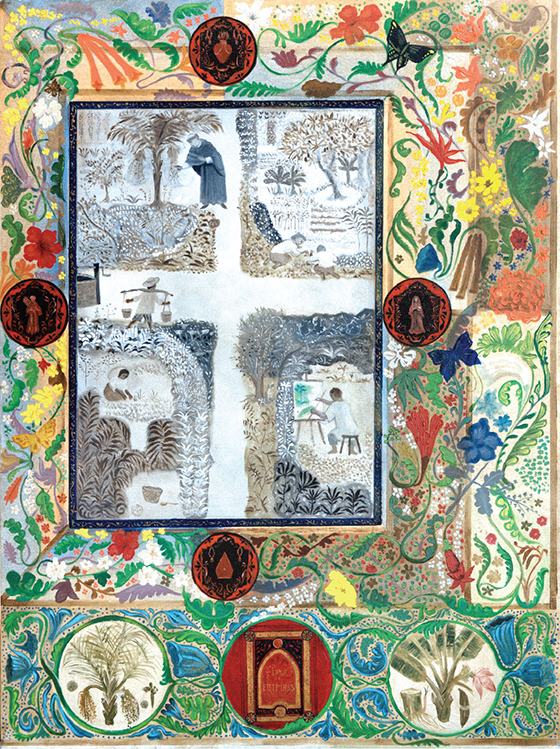

Father Bianco's Garden

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

In Intramuros, ensconced on the grounds of the Church of Saint Agustin, the Augustinian Fray Manuel Blanco created a botanical garden. Born in November 1779, in Navianos de Aliste in Zamora, Spain, he left for the Philippines in February 1804. He studied Tagalog and was so fascinated with local flora that he planted a garden inside the Augustinian Convent of Intramuros. Although he conducted field research mainly in Batangas and Bulacan, he did visited other places. He made extensive documentation of local flora which took him 12 years to finish. The first edition of his invaluable work, Flora de Filipinas Segun el Sistema Sexual de Linneo, was printed by the University of Santo Tomas in 1837.

After Fray Blanco’s death, another Augustinian, Fray Antonio Llanos, was tasked to prepare a new edition, but he passed away before he completed the work. Two other botanists, Fray Fernandez Villar and Fray Ignacio Mercado, produced a third edition of Fray Blanco’s Flora de Filipinas. This monumental botanical work was acclaimed in Spain by the “El Norte de Castilla” (in its issue of October 21, 1883) as “a true monument of glory raised to the memory of Spain by the Augustinian Fathers of the Philippines, so dedicated to the sciences and learning, as shown in their works:’

This HOCUS painting imagines what the garden may have looked like. The symbols surrounding the cross within a square are from the impressive door of the San Agustin Church. Illustrations from Flora de Filipinas are reproduced below the painting. The right lower quadrant shows Lorenzo Guerrero of Ermita, one of Fray Blanco’s illustrators, whose palette gave color to the otherwise dreary existence of the indio during the colonial period. He was Juan Luna’s teacher. He encouraged Luna’s parents to send him to Europe as he had nothing to teach the young genius.

Father Bianco’s Garden

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

El Capitan Chino

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

At first glance, the Chinese in the Philippine colony had all the trappings of Christianized natives. Studiously, they read the Shih Lu or the Doctrina Christiana, printed in the Chinese language by Keng Yo of Binondo. They venerated the mother of God, in La Nuestra Senora del Pronto Socorro, (Ang Birhen ng Biglang-awa).

The Chinese community became increasingly important to economic life, so, the Spanish colonial government organized the Gremio de Chinos or Chinese Guild, in 1870 and appointed a Gobernadorcillo de Chinos to administer the affairs of the Chinese and act as a mediator between them and the Spanish authorities, thus maintaining good relations. However, the Chinese were not allowed to live in Intramuros; they were grouped in areas called the Parian located outside the walls.

In this HOCUS painting, the Capitan Chino is shown inside his luxurious home, seated by a window with the view of an elaborate arch inspired by a 1797 illustration of the Parian. On his left is a blue and white jar, probably a souvenir of a festive event as it is decorated with a pagoda-like tower that was erected at the foot of Puente Grande in Binondo to honor King Fernando VII. There are unmistakably pious signs: on the wall hangs an image of the Blessed Virgin painted by an anonymous Chinese artisan on a fine metal sheet; the “Biglangawa’:

There is a copy of the first catechism in Chinese, Doctrina Christiana, but it is on the floor which hints that the Capitan must have thrown it, in disgust, because he was secretly still a “heathen” at heart. There is a tell-tale opium pipe beside a bowl with the map of Amoy, his hometown in China. Clothed in the finest silk, the Capitan wears a breast plate with a hand-painted, stylized design of the bagua or octagonal shaped alcaiceria, the fabled silk market of the Parian, the source of his wealth and influence.

El Capitan Chino

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

Permanent Exhibit, National Museum of Fine Arts, Republic of the Philippines

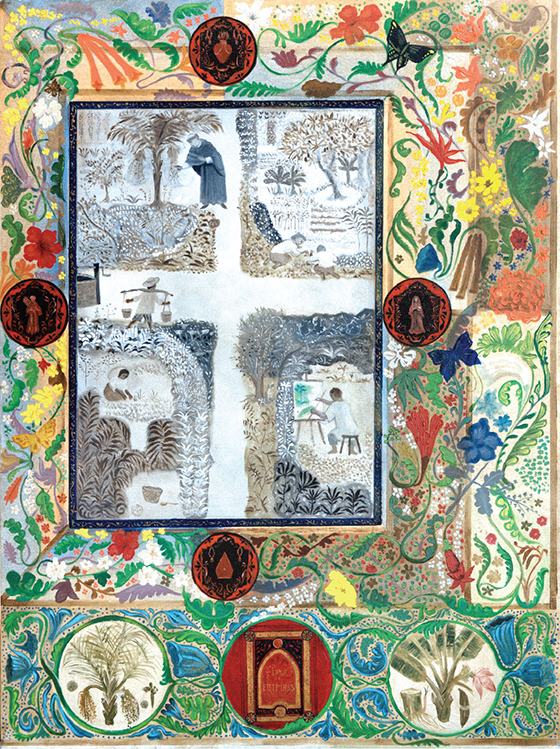

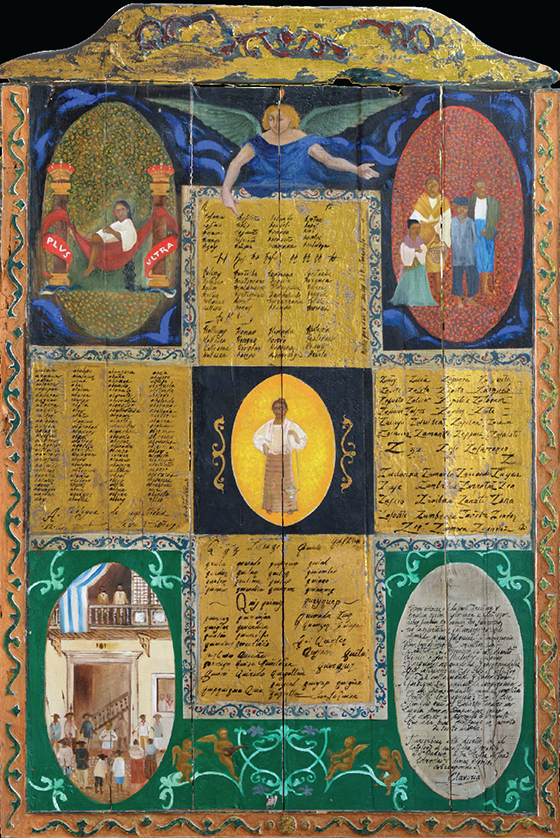

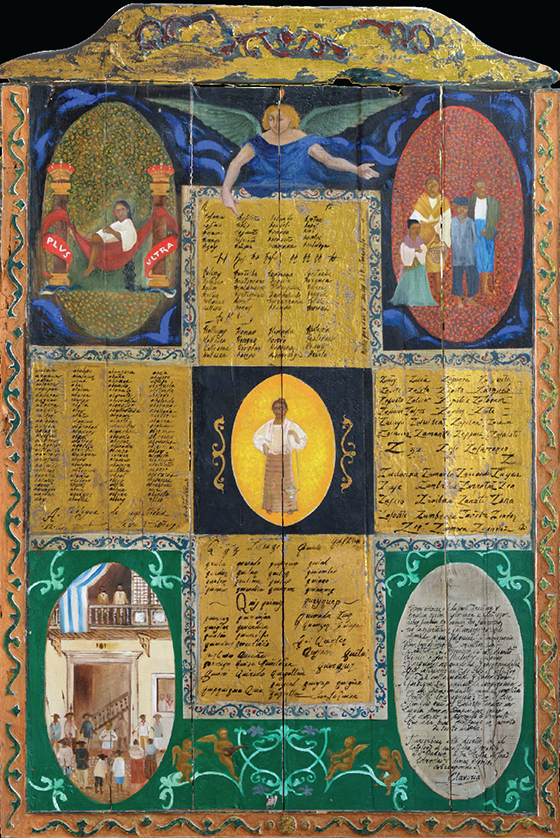

How we Lost our Names

Oil on wood, 5 feet x 3 feet

Narciso Claveria y Zaldua, Governor-General and Captain-General of the Philippines from 1844 to 1849 issued the Cata.logo Alfabetico de Apellidos. This self-styled “Conde de Manila” believed that for reasons of administrative and fiscal expediency, all the natives of this archipelago should have proper surnames. He issued a superior decree in November 1849, ordering the natives to adopt names from the Cata.logo. There were well-defined exceptions to his command, descendants of the native royalty may voluntarily change their names.

Most of the surnames were in Spanish or sounded like Spanish which have led many Filipinos to believe that they descended from Spaniards. Maliciously, surnames were made out of words pertaining to human ordure like “cagas’: or words depicting vices, ailments, deformities-embarrassing surnames which would not have been chosen by those who knew Spanish.

To compel natives to obey, local government officials as well as parish priests were instructed not to issue any permits or official documents to natives not exempted from the decree, whose surnames did not appear in the Cata.logo. Those who reverted to their old names after having registered the new one were penalized with a jail term.

In general, the decree was complied with in all the provinces in Luzon and the Visayas, except for pockets of resistance in Laguna and Pampanga.

How we Lost our Names

Oil on wood, 5 feet x 3 feet

Permanent Exhibit, National Museum of Fine Arts, Republic of the Philippines

The Spanish Dirge

Oil on wood, 5 feet x 3 feet

You can almost hear the dirge being played by these two indios to signal the end of the Spanish Empire where the sun, reputedly, never sets. The Philippines was the haughty Empire’s crepuscule.

In this HOCUS painting, angels from Heaven herald the inevitable and irreversible end of the Spanish Empire to the tune of the indio dirge. The winged messengers of the Almighty descend upon our archipelago, the last jewel of the Crown, to take away its remaining symbols, the Spanish colors, yellow gold and blood red. The Spanish letter ii which is peculiar to the Spanish language. Other angels are fleeing with the bishop’s miter, a Spanish sword, and the key to Heaven, which, according to the friars, must be Spanish. An angel bears the esfera or orb, symbol of the world once dominated by the Empire, another carries a treasure chest containing the wealth extracted from the colony.

A fitting background to the indio musicians is the church of Cuyo, the most peculiar of all churches because it physically embodies the union of Church and State.

The Spanish Dirge

Oil on wood, 5 feet x 3 feet

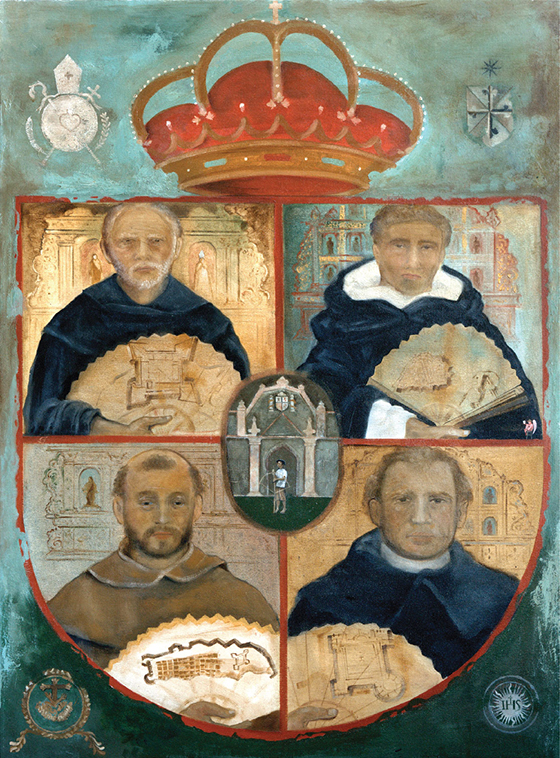

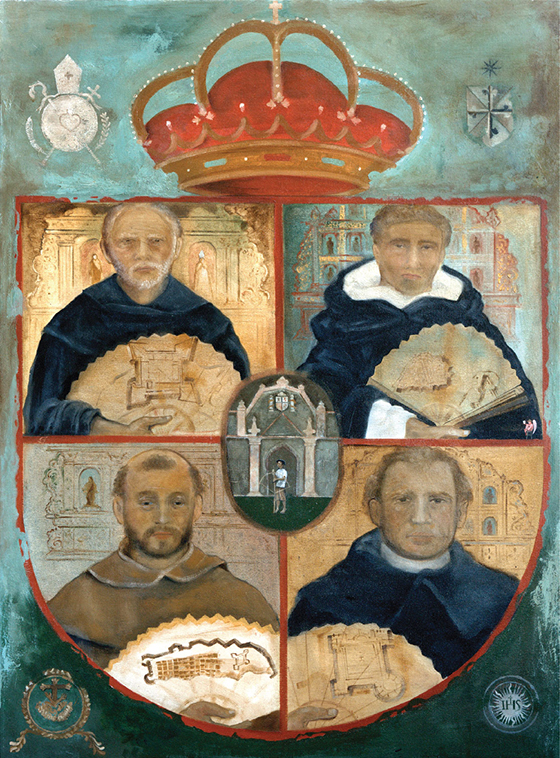

La brisa de los fuertes (The Breeze of the Forts)

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

Four friars from four religious orders-Augustinian, Franciscan, Jesuit and Dominican-who, among others, came to christianize the natives of these islands as shown in this HOCUS painting. Each friar menacingly holds a fan with a diagram of a military fort facing the viewer. From left, clockwise, the Augustinian brandishes a fan with the Fuerza de San Francisco, with four formidable bastions, an embankment and impenetrable curtain wall. This was constructed in Nueva Segovia to watch over the northern provinces. The Dominican brandishes a fan with the schematics of another fort built within his eccelesiatical domain. The Jesuit shows the Fuerza de la Virgen del Pilar in Mindanao while the Franciscan displays the Fuerza de San Felipe in Cavite, guardian of the entrance to Manila Bay.

The Patronato Real de las Indias provided the Spanish Crown with the theological and legal basis to conquer hitherto uncharted lands. The Pope and the King, that is, the Church and the State, entered into a series of agreements which began with the Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella, and lasted until the dissolution of the Spanish Empire in the XIX century. The Patronato stipulated that Christianization justified the conquest of territories.

In their overseas possessions, the Spanish monarchs were duty-bound to defray the cost of sending missionaries, protecting and supporting them with annual stipends of 100 pesos and 100 bushels of rice taken from the tributes imposed on the native population.

In fact, tributes cannot be collected unless the natives were first Christianized. Eventually, the friar-missionaries became the liaisons between the populace and the colonial administration in Intramuros; the bishops and archbishops held sway in the absenceof governors-general. The clergy became so powerful, it influenced State policies. The Holy See made the Spanish monarch the “patron” of the Church in the Indies.

This HOCUS painting shows that the Church (represented by the friars) and the State (depicted by the forts) were one and indivisible, as stipulated by the Patronato Real

La brisa de los fuertes

(The Breeze of the Forts)

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

Permanent Exhibit, National Museum of Fine Arts, Republic of the Philippines

No me toques, corazon infame (Touch me not if your heart be impure)

Oil on wood, 5 feet x 4 feet

This painting was displayed with the permission of the local priest in the Catholic Church ofNaic, Cavite, the same church where Padre Modesto de Castro, author of Urbana and Feliza, served as parish priest in the 19th century. The purpose of the display was to arouse interest in the ancient symbols of our faith. Unfortunately, after being exhibited for months at the entrance of the church, nobody appears to have taken notice of the painting.

The painting was commissioned in order to serve as the historical object that would have been the main theme in a short story that I was writing. The attempt at writing fiction was later abandoned since I later realized that since I was writing about history and the law, it would not do me good if I start writing fiction and confuse my readers. Thus, the idea was abandoned. But the painting, which served as the image backdrop of the aborted story still exist. The members of the religious orders at the foot of the crucified Christ is shown on the left of the painting and on the right is the tombstone of the Countess of Lizarriaga, which can still be found in the ancient Franciscan church of General Trias in Cavite.

Below the picture is a panoramic painting of what Cavite, Cavite used to look like during the Spanish period. On the left are the Poderes, powerful angels carrying what looks like a treasure chest to the Spanish fort of Cavite. The painting is partly based from a story told to me by an old man who claimed to have been hired to enter a tunnel inside the Fort.

He said that there was such a tunnel and it led to the old Franciscan Church whose belfry still stands. He also said that a treasure may be hidden in the bowels of the old church.

Being a boy and impressionable, I believed him and the story has remained in my psyche. On the right is a nondescript icon of a rectangle enclosing a line flanked by two circular objects. This interesting symbol was engraved in stone and situated at the entrance of the Church of Binondo. The last time I checked, the symbol has almost been erased by the shoded and unshoded feet of the Binondo parishioners who were unmindlful of the symbolism situated at the church door. The crowning detail of the panel is the Christian God, Father of Christ. This panel is a combination of the interesting objects, places and structures that we have neglected to see and preserve. As to why the painting should not be touched if one’s heart be not pure? That was the subject of the unfinished short story.

No me toques, corazon infame

(Touch me not if your heart be impure)

Oil on wood, 5 feet x 4 feet

Una iglesia antigua en Basey, Samar (An Old Church in Basey, Samar)

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

In Basey, Samar, there is a church on a hilltop dedicated to St. Michael, head of the host of Archangels that guard the gates of Heaven. The church was built in the 18th century with an inscription carved on its pediment which gloriously proclaims: “Haec Est Domus Dei Et Porta Coeli:’ (This is the house of God and door to heaven). Was this taken literally in those days? What if we adopt a literal interpretation of the inscription found on St Michael’s Church and make the door literally the portal to heaven? The mirror image of the churchis upside down and the two images are attached at the apex, creating an hourglass effect.

Entry into the Church thru the inscribed portal enables one to enter a parallel universe where angels and heavenly winged creatures live a parallel existence.

Una iglesia antigua en Basey, Samar

(An Old Church in Basey, Samar)

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet