Paintings

HOCUS III

Binaril nila si Doktor

Oil on canvas, 3 feet x 4 feet

Why the doctor? He would heal people, even those who could not afford to pay him. In Europe, he studied ophthalmology and worked with two of the best eye doctors. The Frenchman Wecker and the German Becker. Because his mother was going blind, he wanted to cure her. In Calamba, his hometown, he was known as Doctor Aleman (meaning ‘German’ and pronounced as “Uliman”) and his fellow indios were surprised, if not disappointed, that he was not a white foreigner, but a native like them. Bakit binaril ang doctor? (Why was the doctor shot?) Why was Jose Rizal singled out? Why was he executed under such dramatic circumstances? He was banished to rot in Dapitan, imprisoned in Montjuic and Fort Santiago, tried by a kangaroo court, then executed in Bagumbayan at the crack of dawn. He was also maligned beyond the grave with stories about an alleged retraction of everything that he had done in his life. Like a malignant specter, the retraction controversy comes to haunt us in June, Rizal’s birth month, and December, the month of his martyrdom. Yet, the original documents have never been exposed to public scrutiny. The Philippine Independent Church wanted to make Rizal a saint, but that was not good enough for a community of Filipinos, dwellers of the sacred mountains of Makiling and Banahaw. To them, Jose Rizal is not a saint, he is the Filipino Christ.

Binaril nila si Doktor

Oil on canvas, 3 feet x 4 feet

Conjured Apparitions

Oil on wood, 2 ½ feet x 2 feet

Sightings and apparitions, miraculous images and amulets, are deeply embedded in a native Filipino’s DNA. There is the babaylan and catalonan, pre-Hispanic native priestesses in each of us. We conjure apparitions; sightings are commonplace, amulets are miraculous. Did the Blessed Virgin Mary ever come to the Philippines where she is widely venerated and deeply loved? Were there apparitions of the Mother of God in our blighted land? The answer is yes. Since the dawn of Christianization, the Mother of God has made her presence felt in many forms. Probably the earliest encounter—it was not an apparition—was with the Nuestra Señora de Guia which was in fact a female deity carved of dark wood whose hands did not even meet in a Christian clasp. As the annals of the Manila Cathedral report, in 1571, some Spanish soldiers who came with Legazpi to Manila were strolling down a beach (Manila Bay, where Ermita is now located) only to see a bunch of natives venerating a dark wooden statue, set on a lush pandan that abounded in the area. They stole the icon, surrendered it to a missionary who dressed her up European-style. She became Nuestra Señora de Guia, patroness of travelers, and today of OFWs (overseas Filipino workers). The story of Nuestra Señora de Caysasay is more mysterious—there is an apparition, then an image.

The apparition was a reflection on a stream or rivulet, the Balon de Santa Lucia (Well of St. Lucia) where a Taaleña called Maria Talain used to draw water. Our Lady appeared to her in the form of a reflection. The water from that well was said to be miraculous so someone carved an arch out of coral stone with Our Lady’s image and placed it over that stream with healing waters. Because of such mysterious and controversial apparitions, I asked Custodio to paint the Virgin and make her look ancient to fool the eye into believing that it was painted during the Spanish period. Only the title of the Virgin (Nuestra Señora de Buhay na Tubig) betrays her recent origin—it is a place in Imus, Cavite, which I use as my refuge. The year 1795 represents the year Imus, Cavite, was founded and not the year the painting was made. This painting does not intend to ridicule a sacred Catholic symbol, but rather to show that one can conjure belief based on the marriage of art and dogma.

Conjured Apparitions

Oil on wood, 2 ½ feet x 2 feet

Dito po sa Amin

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

In Cavite City sits the town of San Roque. It was named after Saint Roch, a 14th century Catholic saint who ministered to those stricken with the Black Death until he himself was covered with incurable sores and pustules, symptoms of bubonic plague. He retreated to a dense forest to await death. A dog, the legend continues, brought him his daily bread until he was miraculously healed. In the Philippines, he is known by his Hispanized name—San Roque.

The small town in Cavite still carries the saint’s name which no living mayor nor councilor has dared to change, and in it was born this charming 19th century folk song:

Doon po sa amin

Sa bayan ng San Roque

May nagkatuwaan Apat na pulubi

Nagsayaw ang pilay

Umawit ang pipi

Nanood ang bulag

Nakinig ang bingi

(In our town of San Roque There were four beggars

Who wanted to have fun

The lame danced

The mute spoke

The blind man saw and

The deaf listened.)

The four beggars of the ditty walk towards the store; actually, they are Americans carrying the battleships that laid waste to the wooden-hulled naval fleet of General Patricio Montojo during the Battle of Manila Bay. Below and to the left of the viewer is a beggar dressed in the blue uniform of the U.S. Marines holding in his left hand the battleship Concord and in his right, the Raleigh. Inside the blue-suited marine’s back pocket is the battleship Maine, the one docked at the Havana harbor when it exploded mysteriously, killing more than two hundred Americans. In front of the man in blue is another beggar wearing a pilgrim’s hat and holding with his right hand the battleship Olympia while reading the lyrics of the Star-Spangled Banner as if he were not blind.

To the right of the painting is a one-legged man with a sailor’s hat, holding a Krag and the battleship Petrel. Behind him is another beggar, deaf as a bat, clutching the battleship Boston. These two ships also figured prominently in the Battle of Manila Bay. Around them from left to right, are what remains of the Spanish ships Reina Cristina, Ulloa and the Castilla—part of the obliterated Spanish fleet of Admiral Patricio Montojo, head of the once invincible Spanish Navy. On the left of the man who is hard of hearing is a Filipino boy whispering to his deaf ear while holding the USS Thomas, the transport ship that ferried the Thomasites to our shores, to educate and pacify us after being thoroughly civilized with a Krag.

Dito po sa Amin

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

Our Lost Eden

Oil on canvas, 6 ½ feet x 4 feet

The imposing Igorotta, that serves as the central figure of this painting, was borrowed from the frontispiece of a book written by the French traveler, René Jouglet, in the 1930s. He was so fascinated with gold and treasure hunts that he once embarked on a quest for Limahong’s gold

cache and wrote about it.

With sheer romanticism, he described the Philippines as a scattering of misty islands of picturesque volcanoes and mountains that “contain mankind’s main source of sustenance—gold.” He fueled the misguided search for El Dorado.

His words clearly explain why the many tribes in the mountainous provinces fought wars as old as the mountains themselves.

After the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1898, Spanish sovereignty was transferred to the United States of America; Worcester was appointed a member of the Second Philippine Commission by William Howard Taft. He immediately informed Secretary of War, Elihu Root of the existence of that certain place described by Domingo Sanchez with a temperate climate and mountains of gold.

As a result, Sec. Root gave orders to open the Philippine Islands to all Americans. When Worcester reached Baguio for the first time, he realized that Domingo Sanchez, the Spanish bureaucrat, was not exaggerating. Baguio was amazingly cool, pristine, with abundant water and fertile soil conducive to growing temperate fruits and vegetables.

It was also ideal for pasturage. More important was the abundance of gold, copper, and silver. An expedition was organized and so was a Philippine Commission headed by Dean C. Worcester. Captain Charles Mead was selected to build the road to Baguio, the gateway to the Mountain Province.

However, Mead the military man failed in his mission because he was unable to deal with a multi-ethnic workforce. He was replaced after several months by N.M. Holmes who, in turn, also had to be replaced, in 1903, by Major Lyman W. Kennon who finally got the ball rolling.

After the Benguet Road, now known as Kennon Road, was opened on March 27, 1905, several events took place.

The Presidential Order signed in 1903, which had set aside 535 acres (216.85 hectares) for a military reservation was confirmed through General Order No. 48. Moreover, it was more than doubled to 1,433 acres (580.16 hectares) by virtue of another Presidential Order of Theodore Roosevelt.

It became evident that the establishment of military reservations were mere excuses to wrest land from its native inhabitants. Consequently, the military reservation was again increased by 349.64 acres by virtue of Executive Order 1855, which meant more ethnic communities were displaced.

The Igorrotes were suffering the fate of the Cherokee Indians. This HOCUS painting shows how the workers built the Benquet/ Kennon road. They constructed retaining walls of stone to hold back the earth that could cause landslides. There are men clambering up the steep slopes using bamboo scaffoldings, porters carrying loads, bunkhouses built for laborers, carromatas, and base camps at the foot of what would later be known as Kennon Road.

The Igorotta, frontpiece of René Jouglet’s travel book, is the allegory of our lost Eden. Hundreds of workers inured to danger and hardship scale the mountains ostensibly to “Christianize and civilize” the pagan highlanders, but in truth, the Americans like the Spaniards before them, were afflicted with the Ël Dorado disease, an incurable hankering for gold.

An American named Samuel E. Kane was also fascinated by the Mountain Province. He came on board the transport ship Sheridan and was a member of the Thirty-Third U.S. Volunteers, part of the invading US army. Kane spent 30 years in the Mountain Province and wrote a sensationally titled book, Thirty Years with the Philippines Head-Hunters, after which he returned to the United States.

In 1931, he came back only to find out that most of the people he had known were already dead, but that two of his former secretaries were appointed governors. He then wrote the following in the epilogue of his book: “Looking down from sacred Mount Polis, or from any pass of the lofty Malaya Range, on the little groups of huts with the Igorots squatting over glowing fires, one loses the feeling of distinction between man and nature. Yet it is only a matter of a few years, if progress is to continue at the pace set the past three decades, before this beautiful natural territory will become completely Americanized—with paved highways, ugly signboards and gasoline stations. The rising generation has already broken its link with the past.

Fifty years hence when the tribal chiefs and elders have gradually died out, there will be little left to remind the young Igorots of the days when the drums and ganzas of the head-hunting canyaos resounded throughout the land.” You can keep your regrets, Mr. Kane. You stole our Eden, we lost our Paradise.

Our Lost Eden

Oil on canvas, 6 ½ feet x 4 feet

Luna, Arquitecto

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

This HOCUS painting, albeit different from the other paintings that we have done, shows our nation’s history in the eyes of a little boy. He is Andres Luna de San Pedro, son of the greatest Filipino painter in the 19th century, Juan Luna.

In this HOCUS painting, which is the cover of a book entitled Luna, Arquitecto, the young Andres Luna de San Pedro is in a make-believe soldier’s uniform as he was painted by his father. He is shown with images that later defined his life—a self-portrait of Juan Luna, copied from a photograph which also showed Jose Rizal with a sword. Above him on his right is a famous image of Antonio Luna, Juan Luna’s brother.

The hot-tempered Luna made enemies in the cabinet of President Emilio Aguinaldo, antagonizing Aguinaldo himself. Beside him is a statue of a famous Degas dancer, symbolizing Andres Luna’s wife Grace McCrea who was trained as a modern dancer.

A portion of a portrait painted by Juan Luna of Paz Pardo de Tavera, his illstarred wife, is above the fireplace. Paz was killed together with her mother, Doña Juliana, by Juan Luna himself. In front of Andres Luna is a rug which shows the “Spoliarium” which won a gold medal at the Exposition Nacional de Bellas Artes and made Juan Luna famous in Paris, Spain, and Italy.

The interior of the house which his family occupied, (e.g. the door at his back and the fireplace) are faithful to the arrangement of their rented residence at Villa Dupont in Paris, the place where Andres Luna’s mother and grandmother were murdered.

Andres Luna de San Pedro at the tender age of five, was the lone witness to a horrifying double murder: out of jealousy, his father shot dead his beloved mother and grandmother in their home in Paris.

He was the only son of the most celebrated Filipino painter in Europe—Juan Luna y Novicio. His uncle, General Antonio Luna, Commander of the Philippine Revolutionary Army, taught him how to handle a sword.

A maternal uncle, Dr. Trinidad H. Pardo de Tavera, was a brilliant scientist and scholar, scion of a wealthy mestizo family from Manila who held prestigious positions in the American colonial government. There was probably never a moment of peace in his beshrewed life. Despite his personal tragedies, the wars and conflicts that he witnessed, he created architectural masterpieces which were objects of pride and awe. Sadly, most of those architectural treasures now exist only in faded photographs and fading memories.

Luna, Arquitecto

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

Hocus Triumphant

Oil on wood, 5 feet x 4 feet

Using a Brobdingnagian pen, the anghel de cuyacuy slays a giant crab, the Filipino symbol of the sins of envy, selfishness, and the resentment of the success of others.

Filipinos relate to the actions of crabs which, when placed inside a basket before their inevitable transformation as viand, claw down other crabs that manage to reach the top, ensuring that all of them, without exception, will be cooked as food.

This phenomenon, which behavioral scientists call the “crab-bucket mentality” is a course of action which can be succinctly phrased as: “If I can’t have it, neither can you.” Such pattern of behavior is common among us and is the reason why we always end up being stewed and cooked in our own juice. The dilemma of the crab may be put into words by an allegory attributed to a Jewish rabbi named Haim of Romshisshok and may be the source of the proverb: “He who sups with the devil must eat with long spoons.”

The puzzling proverb may be unraveled by the following interpretation: Food is plentiful in a place which the rabbi failed to identify (perhaps it was Romshisshok), but because they were given long spoons, they refused to help each other and instead tried to use the unwieldy utensils on their own.

As a result, they all starved to death. They could have lived had each one fed the other from across the table using the same long spoons.

This painting shows the HOCUS angel about to end the existence of the Filipino symbol of magnificent foolishness—the decapod crustacean commonly known as the crab.

Hocus Triumphant

Oil on wood, 5 feet x 4 feet

Santo ng Bayan

Oil on canvas, 2 ½ feet x 5 feet

Rizal’s foremost biographer, León Ma. Guerrero, wrote in The First Filipino: “The Filipinos had chosen Rizal even before he died, and his final martyrdom was only the confirmation of a spiritual dominion that even the Katipunan acknowledged by an uprising invoking his name. The choice was ours. It was Rizal who lifted up the hearts of his generation and who is enshrined by the Nation and the Republic he made.” The drama that surrounded Rizal’s execution was meant to chastise the natives, in particular the filibusteros into abandoning their anti-Spanish activities. However, it had the opposite effect because Rizal faced death so calmly, like those Christian martyrs, like a saint Bishop Aglipay was not the first nor the last to compare Jose Rizal to Jesus Christ. In 1954, diplomat and academic, Salvador P. Lopez, wrote: “I mentioned Rizal in the same breath as Jesus Christ. I do not consider this a blasphemy. In purity of heart, in love of fellowmen, in single-handed devotion to the highest moral principles, in fearlessness of death, Rizal invites a comparison with the Man-God of Galilee…” (Diliman Review, vol. II) The late historian Prof. Paula Malay wrote, also in 1954, that in at least three towns in Leyte there were chapels where Rizal was venerated as a god and people knelt in fervent prayer before his statues. In Legaspi City, the Pantay-Panatay community called themselves Rizalinos. Barefooted, they walked to the monuments of Rizal on the days of his birth and execution to perform their rituals and celebrate their own kind of holy mass. In Tayabas, Quezon, there are groups called “colorum” with chapels dedicated to Jose Rizal, at the foot of Mounts Banahaw and San Cristobal. Similar cults exist in Tarlac, Laguna and Bulacan. Their members, dressed and veiled in white, silently march to the Rizal monument at the Luneta on 30 December. After the official commemorations of the City of Manila and the National Historical Commission, they are allowed to offer flowers and chant their prayers to our national hero, their god.

Diplomat and historian, Leon Ma. Guerrero wrote in The First Filipino: “We reserve our highest homage and deepest love for the Christ-like victims whose vision is to consummate by the tragic ‘failure’ the redemption of our nation. They stand above the reproaches and recriminations of human life, and are blessed with true immortality. When at their appointed time, they die, we feel that all of us have died with them, but also that by their death we have been saved.” In his last poem, Jose Rizal exclaimed: “Ah, que es hermoso caer por darte vuelo; morir por darte vida!” which Andes Bonifacio translated: “… laking kagandahang ako’y malugmok, at ikaw ay matanghal, hininga’y malagot, mabuhay ka lamang.”

Santo ng Bayan

Oil on canvas, 2 ½ feet x 5 feet

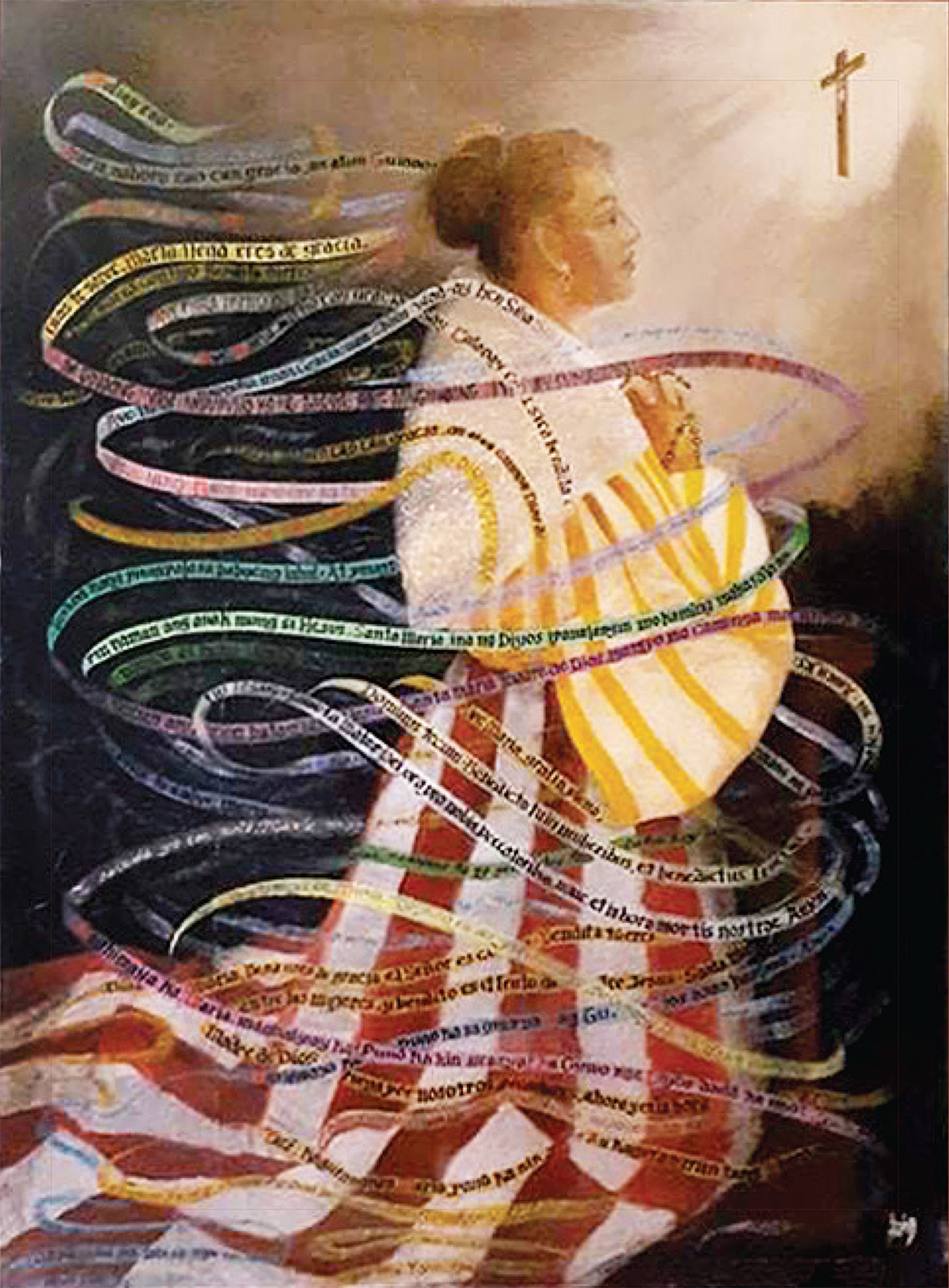

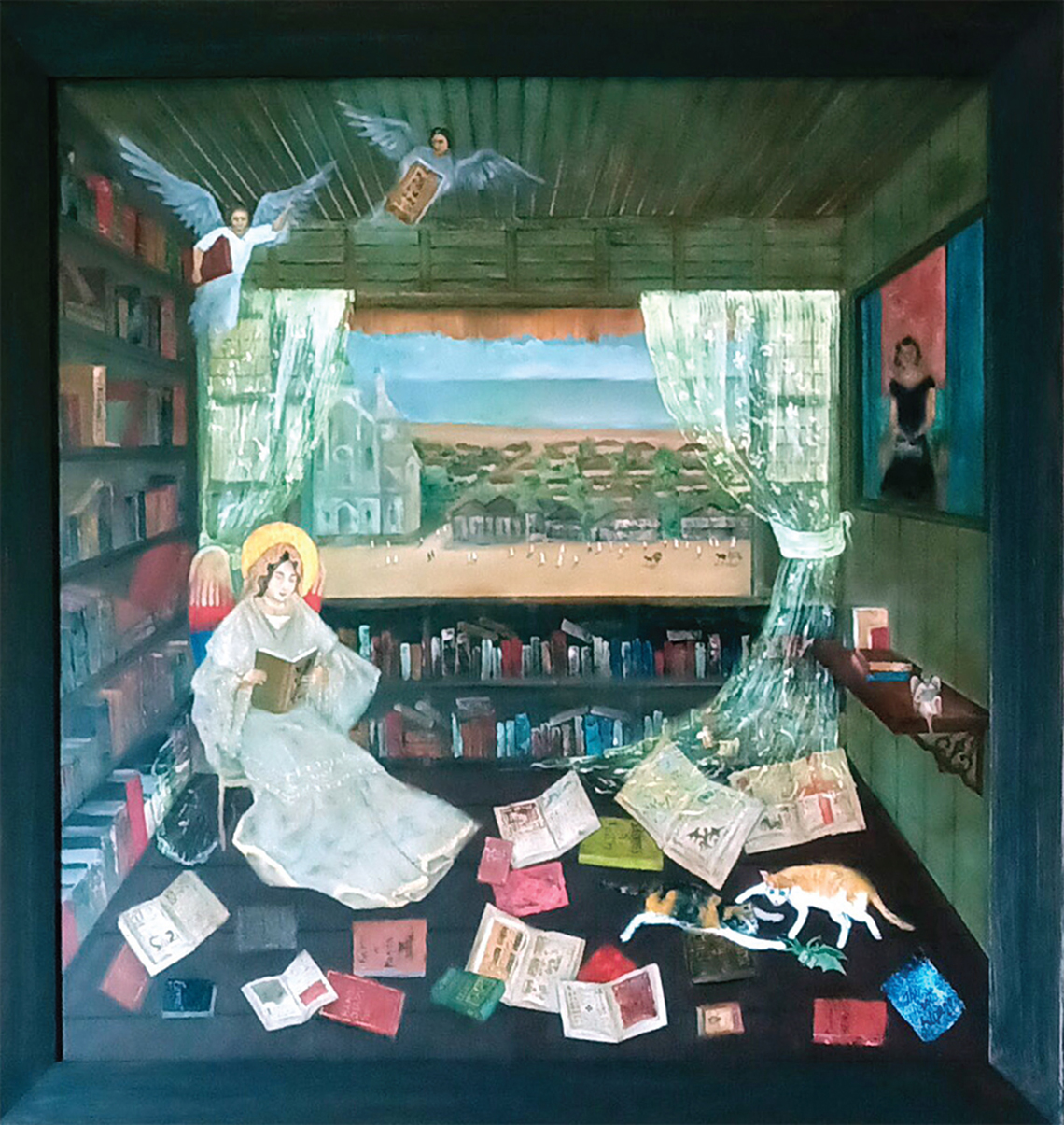

Ave Maria

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

Native Filipinos like other colonial subjects of Spain in South America were made to pray to new deities: the Mother of God, the Blessed Trinity and a host of saints. At the outset of evangelization those prayers were in Spanish and Latin, strange tongues to the natives of these islands. As the early missionaries learned the local languages, they translated these prayers so the indios could communicate with the Creator. Or maybe it was the other way around, with the little Spanish they picked up, the natives translated the prayers into their own languages. Raising his eyes to a European-looking image in church, the Ilocanos would say, “Ave Maria nga napnocat iti gracia…”. Ensconced in their private oratory, a Tagalog family intoned: “Aba Ginoong Maria napupuno ka ng gracia…” Huddled before the altar of the Manila Cathedral, the “Junta Directoria de las Hijas de Maria” fervently sang their prayer in Spanish, “Ave Maria, sin pecado concebida….” The Kapampangan would pray in sonorous voices, “Bapu Maria, mipnu ka king grasya; Ing Ginuong Dios atyu keka, Nuan ka karing sablang babai.” The beatas and novicias in conventos, trained by madres superiora, could pray in Latin, a now dead language: “Ave Maria, gratia plena, Dominus tecum, benedicta tu in mulieribus.”

The Cebuanos, the first to be Christianized, would recite the holy words in their tongue: “Maghumayra ka Maria, napuno ka sa grasya, ang ginoong Dios anaa kanimo…” In this HOCUS painting, a Filipino woman intones the Hail Mary to venerate the Mother of God. The language of the prayer matters not; whether in Latin, Spanish, or the various Philippine languages, blind faith brings eternal hope to a heart full of grief.

Ave Maria

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

Christianity and the Krag

Oil on wood, 5 feet x 3 feet

With the sword, Spain converted us to Christianity that made us subjects of a king. The United States of America came “to civilize and Christianize” us with the Krag that made us subjects of a foreign President. What is the difference between the Sword and Cross and the Krag and Christianity?

In this HOCUS painting, a new choir of angels bearing the flags of the Protestant denominations, follow hard on the heels of the American conquerors to submerge the Roman Catholic Faith.

The flags bear the names of various denominations brought to the Islands by the new imperial masters.

1. Protestant Episcopal Church

2. Baptists Church

3. Disciples of Christ

4. Presbyterian Church

5. Church of the United Brethren

6. Methodist Episcopal Church

7. Christian and Missionary Alliance

8. Seventh-Day Adventist Church

9. Congregationalists Roman Catholic priests began to openly attack the Protestants.

During the early years, the word “Protestant” itself was equivalent to a slur. Although the Catholic Church failed to stem the tide, the Roman Catholic faith had a 333-year advantage: it had grown very deep roots in the Filipino psyche, impossible to extricate.

Today, Roman Catholicism is still the predominant religion. American industrialists and businessmen viewed the Philippines as an abundant source of raw materials for their factories and, at the same time, a large market for their export products. That is why the acquisition of the Philippines was imperative. Hand in hand with those economic policies is the Protestant work ethic of thrift, hard work and efficiency. German sociologist Max Weber affirmed that Protestantism was the seedbed of modern capitalism.

Christianity and the Krag

Oil on canvas, 5 feet x 3 feet

An Empire in the East

Oil on wood, 4 ½ feet x 3 ½ feet

Christianity had already penetrated China as early as the 7th century; Spain was still a disunion of kingdoms, the “Reconquista” of Al-Andalus had not even begun.

By the 13th century, the peripatetic Marco Polo reported that there were at least 700,000 “hidden” Christians in China. The Chinese Christians could not openly profess their faith because in the 9th century, Emperor Wuzong, a devout Taoist who reigned from 840 to 864 A.D, banned Christianity in the Middle Kingdom.

What evidence is there to prove the early arrival of Christianity in China? There is a remarkable stele carved in 781 A.D. in the old capital of the Tang dynasty with inscriptions alluding to the existence of the Christian faith in the celestial empire.

A stele is a huge stone slab upon which is carved narrations of great deeds, epics, poetry, events that may seem insignificant to us now but were important then. The words Da Chin or Daqin are etched upon it in ancient Chinese calligraphy.

The inscriptions relate that Christianity came to China from Syria. It was described as the religion of light and brightness. There are also Syrian inscriptions on the stele with names of people and the word Ma which means “old teacher.”

According to the 2,000-character inscription of the stele, a Syrian named Alopen, leading a band of missionaries like himself, arrived in Chang’an, then the capital of the Tang dynasty. Their objective was to proselytize and preach the Gospel. Because the Syrian missionaries came in peace, bearing the Cross and not the Sword, they were welcomed by the Chinese.

This HOCUS painting is allegorical but based on facts. On October 1, 2000, Pope John Paul II canonized 120 men, women, and children, “Christians in hiding,” who sacrificed their lives for the Catholic faith during the period 1648 to 1930. It is a historical fact that in Japan, friar-missionaries were immediately put to death because they were known not only as conveyors of the Faith but also as purveyors of conquest.

They came with soldiers; the Cross was escorted by the Sword to conquer souls and territory. The crosses at the center of this HOCUS painting are crowned with inscriptions from the Nestorian Stele which unveil the fountainhead of Christianity in China: “When the pure, bright, illustrious Religion was introduced in our Tang dynasty, the scriptures were translated and churches were built.”

At the foot of each cross which serves as the aisle, there are symbols of the Spanish empire which attempted to convert Asia to Christianity with the Cross and Sword.

An Empire in the East

Oil on wood, 4 ½ feet x 3 ½ feet

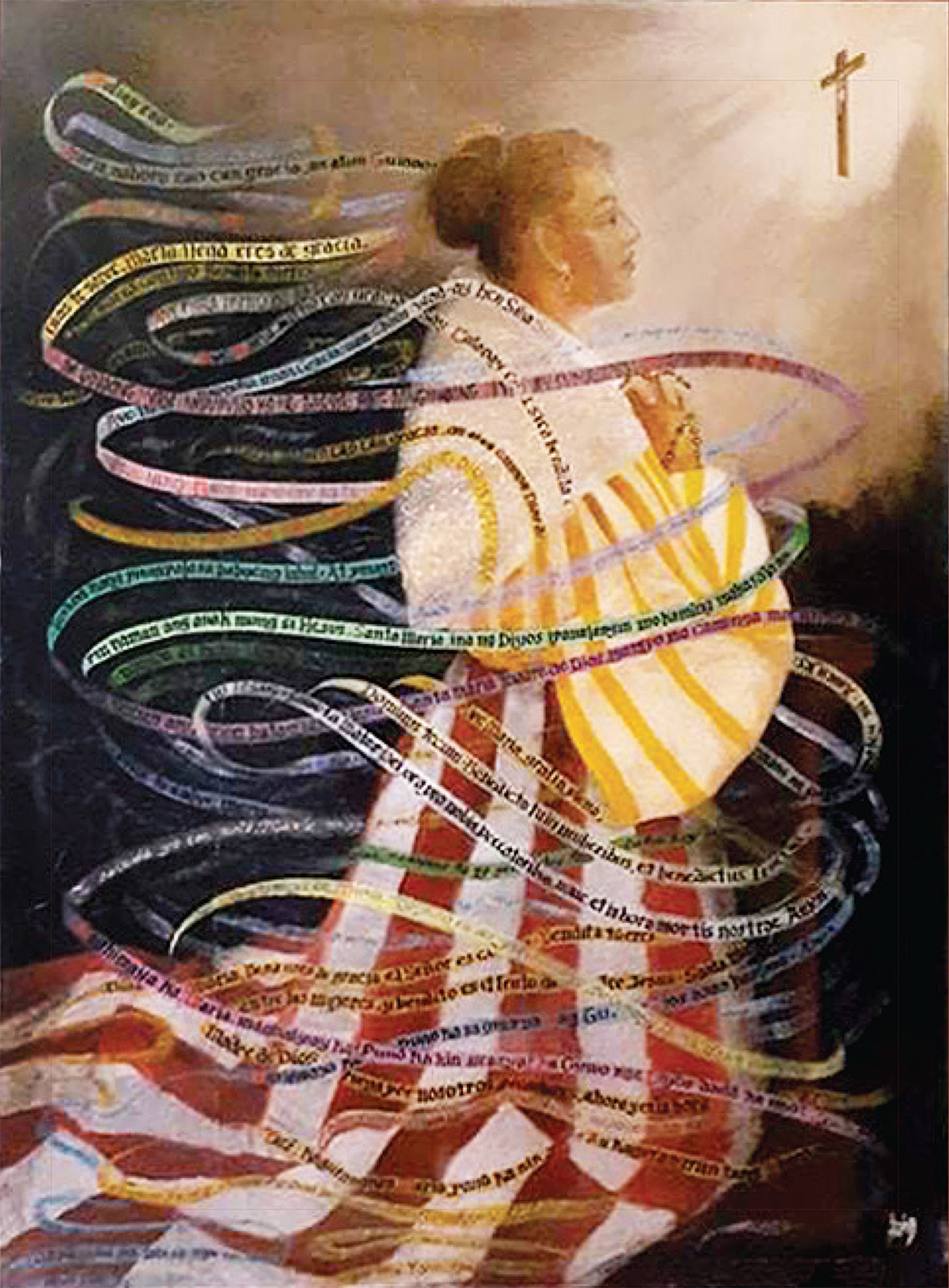

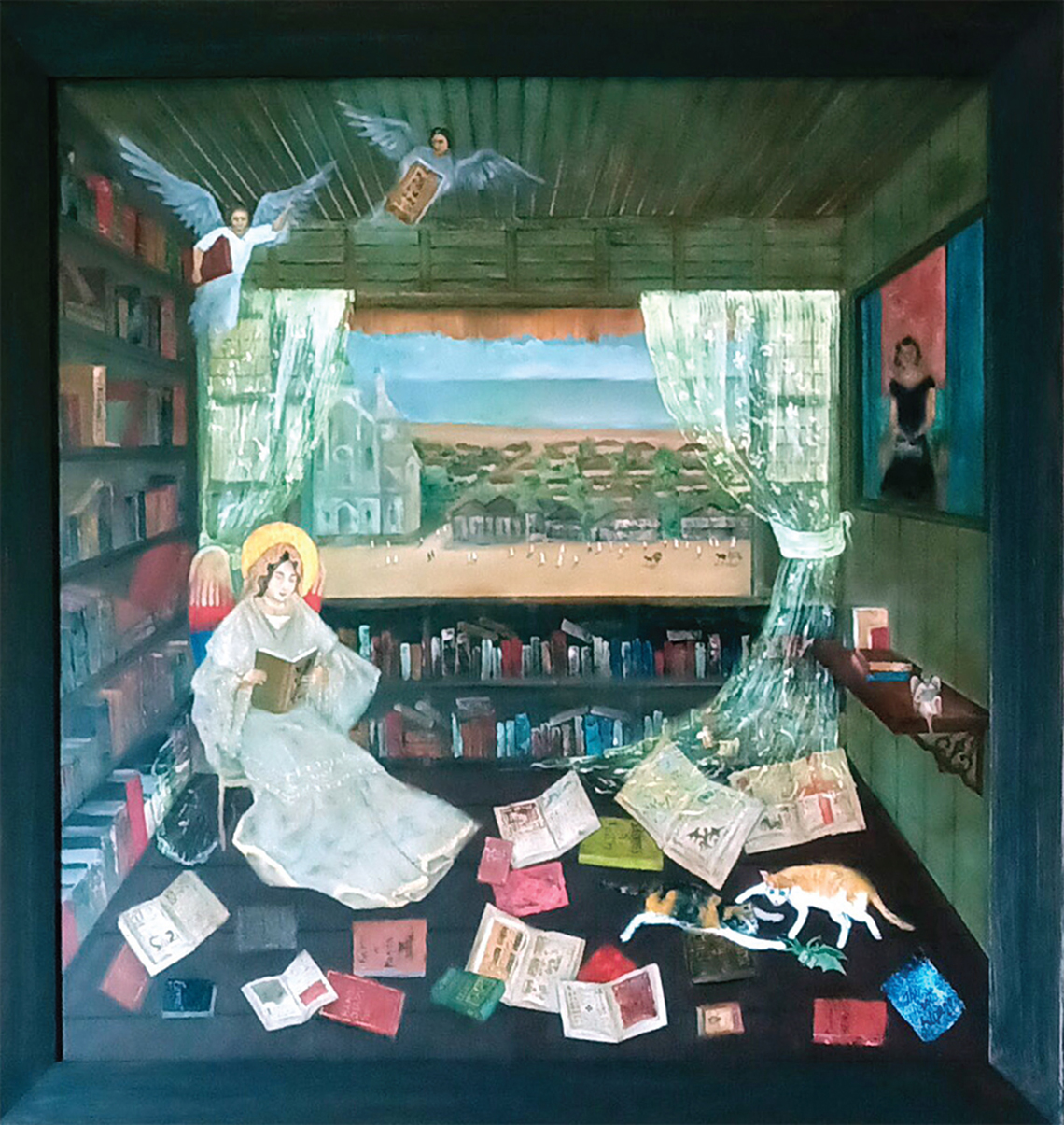

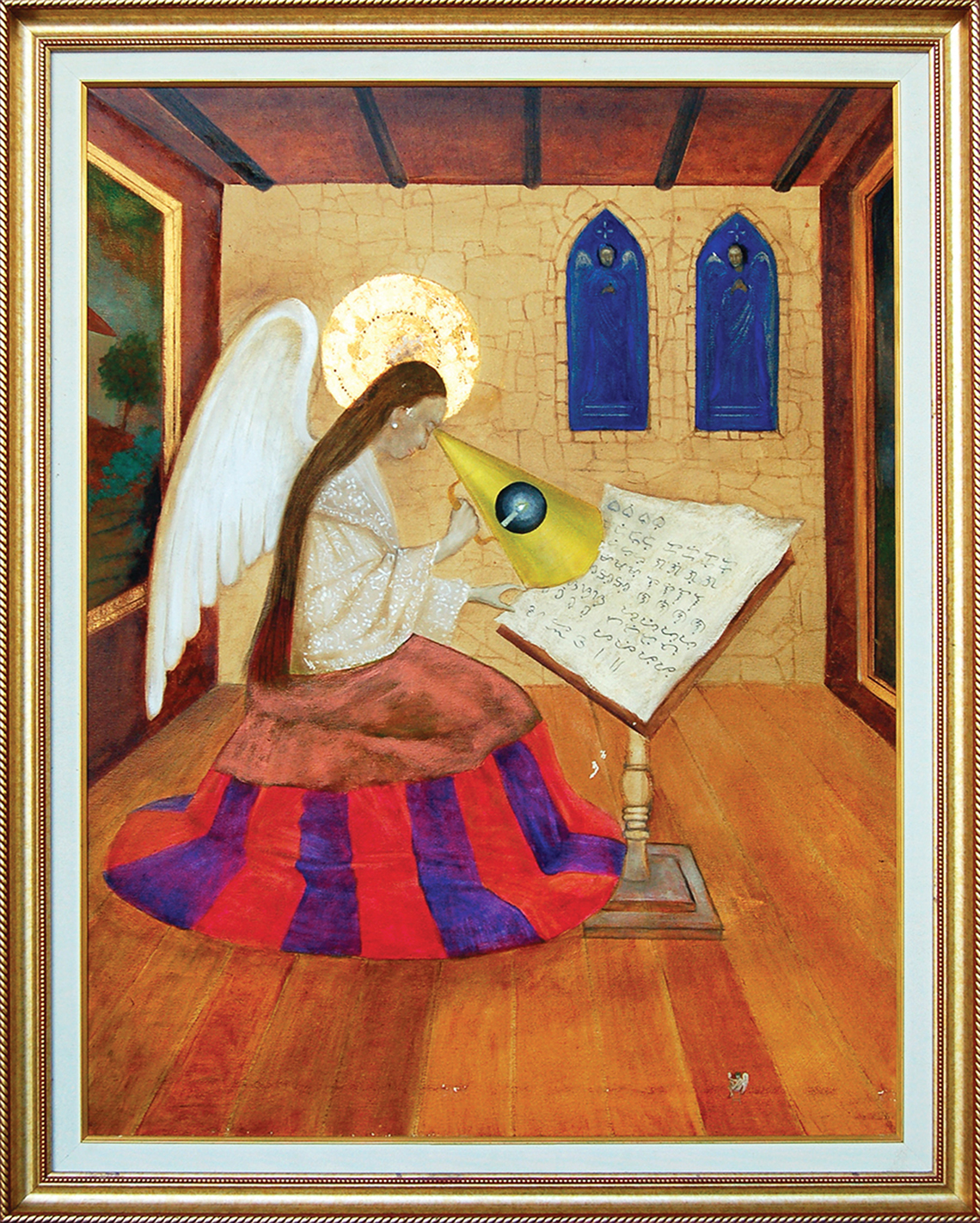

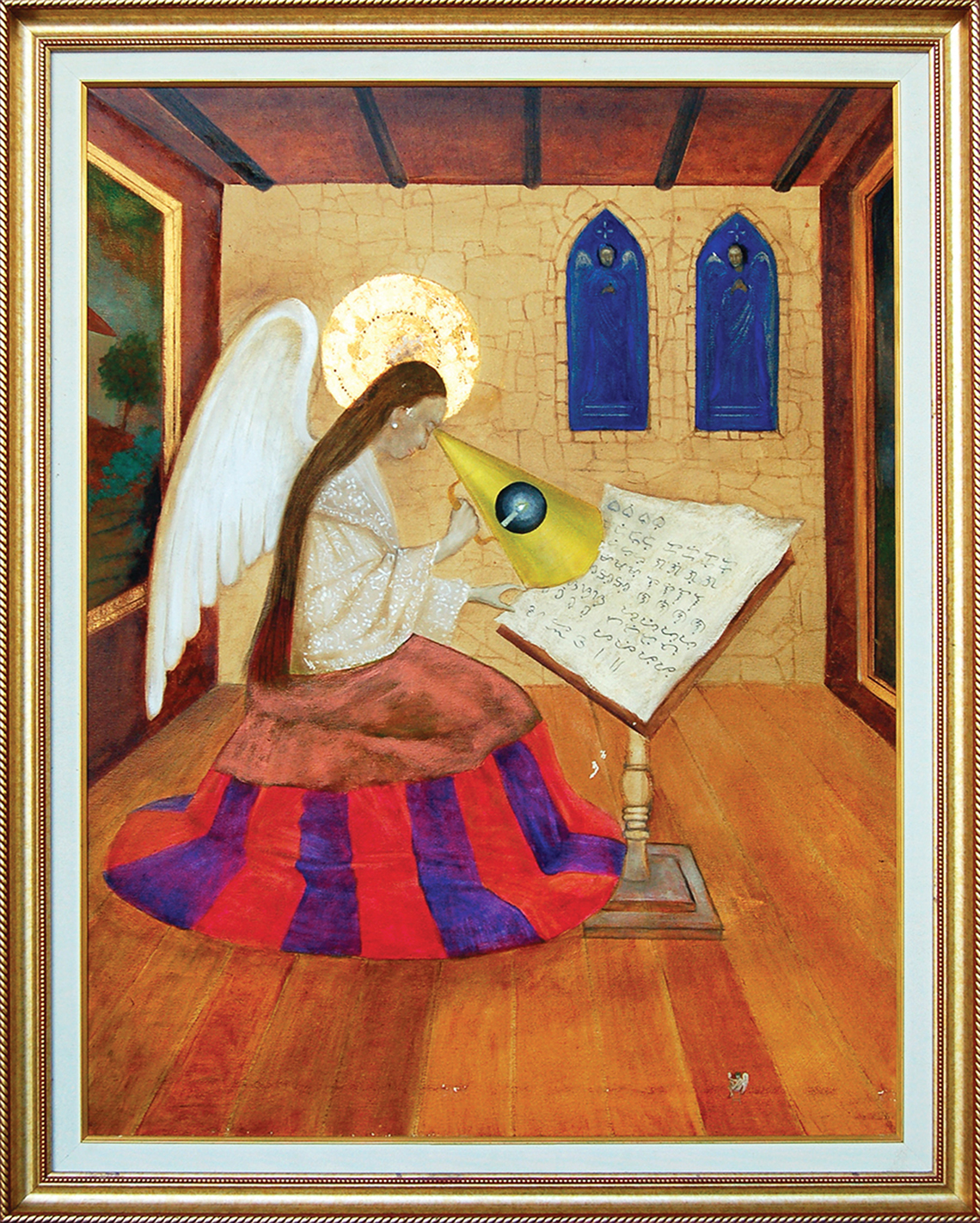

Opening the Books of the Past

Oil on canvas, 2 ½ feet x 2 ½ feet

A discerning eye will see how several layers of the past are melded in this allegorical painting. An angel has taken human form and is dressed in what we now call a “Maria Clara,” reminiscent of the tragic heroine of Noli Me Tangere, José Rizal’s first novel.

However, far from being a tragic figure, she is surrounded by books. She is opening the books of the past. Among other concerns, she wants to know what native women were like before the Patronato Real cast its long shadow on our shores.

Opening the Books of the Past

Oil on canvas, 2 ½ feet x 2 ½ feet

The Days of the Plague

Oil on canvas, 6 feet x 7 feet

This HOCUS painting shows painted figures trapped in the National Museum leaving their safe abode to become effigies of death during the days of the plague. The soldiers from the “Antitesis del angel de cuyacuy/telaraña del colonialismo” (The Antithesis of the Anghel de Cuyacuy/The Cobweb of Colonialism) step out of their canvas.

From Quadrícula (HOCUS II) indio Filipino soldiers of the gigantic “La Quinta” (The Fifth) twin paintings follow suit. The musicians from the “Escuelas y rosarios” of HOCUS I have descended the stairs of the school in Bol-joon while the missionary-priests of “Los recien llegados” (HOCUS II) are being pulled down to occupy ethereal space. On the left we see the “Antitesis” accounting for souls, aided by an angel from the “Triduana” (HOCUS II), with their respective “libros de almas” (book of souls) and scales. A heart is being weighed against a feather.

The ancient Egyptians believed that you could enter Paradise only if your soul is as light as a feather. In the tumult, a skeleton is seen holding two hourglasses: in one time has run out, while in the other there is still time to live. The scene is a grim reminder of what life has become during the days of the plague. June 9, 2020: Outside, the contagion is raging. It was only three months before that news of a deadly and fast-moving virus reached us. It will only be a matter of time before the virus devastates us and all other countries that dot the planet. Surely enough, in less than a month, the contagion spread to Italy, Spain, the United States of America, and, as if smuggled by invisible ships, the virus slithered into the Philippines.

The government ordered a lockdown, Wuhan style. People were terrified of getting the virus, or of becoming launching pads or carriers of the deadly disease, unwittingly spreading the infection. Health protocols were rapidly imposed. Fear of death made people compliant.

On the last day of the HOCUS II exhibit, we were informed that the National Museum of Fine Arts had to go into a lockdown. All the HOCUS paintings still on display were incarcerated. Thus, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, HOCUS II became the longest-running non-permanent exhibition in the National Museum of Fine Arts.

The Days of the Plague

Oil on canvas, 6 feet x 7 feet

Luminous

Oil on canvas, 3 ½ feet x 3 feet

In the beginning, there was the babaylan. To his eighteen-year-old sister Trinidad, he wrote that German women were all “tall, stout, not very blonde but blonde enough.” They are very amiable, sincere, serious and industrious.

“They do not care very much about clothes and jewelry, and go everywhere walking as briskly as the men, carrying their books or baskets, paying attention to nobody else, and intent only on their duties…They are very fond of housework and learned to cook as assiduously as they might learn music and painting. If our sister Maria had been educated in Germany, she would have been remarkable, because the Germans are active and half-masculine. They are not afraid of men and care more for the substance of things than for appearances.” He continued to say that it is a pity that the native Filipino women think they should adorn themselves with luxurious clothes instead of with education.

In the provinces, Filipinas make up for this lack of education by being industrious. Filipinas have a “delicacy of feeling” which he had not encountered in European women.

Significantly, he concluded: “if these qualities with which Nature there endows her, were ennobled with intellectual ones, as happens in Europe, the Filipino family would have nothing to envy the European.” A few years later, in 1889, he did hear about a breed of Filipino women he never thought existed, the 20 young ladies of Malolos, townmates of Marcelo del Pilar. They wanted a put up a school where they could learn how to speak Spanish; they had written a letter to the authorities asking for permission.

The parish priest objected but the ladies took advantage of a visit of Gov-Gen Weyler to their town, literally ambushing him and cajoling him into signing the permission. Marcelo del Pilar had asked him to write them a letter of encouragement while they were in the midst of conflict. It was probably the longest Rizal wrote in Tagalog. Rizal told the young ladies of Malolos that had he had not heard about the school project and what they had to go through to obtain their goal, he would never have imagined that women like them existed in the country. “I pondered long on whether or not courage was a common virtue of the young women of our country….” before he wrote the Noli Me Tangere. He said he couldn’t remember meeting women like that, only a few conformed to that ideal. He said he was wrong about not finding courageous women and he received news about them with great joy. “Now we are confident of victory,” he said, “The Filipino woman no longer bows her head and bends her knees; her hope in the future is revived, gone is the mother who helps to keep her daughter in the dark, who educates her in self-contempt and annihilation…You have found out that God’s command is different from that of the priest’s, that piety does not consist in prolonged kneeling, long prayers, large rosaries, soiled scapulars, but in good conduct, clean conscience, and upright thinking.” He told them that “it all starts on a mother’s lap because it is the women who open the minds of men,” which meant that a good mother raises her children “close to the image of the true God.”

Rizal also wrote that mothers should instill in the minds of their children “every good and desirable idea” like honor, sincerity, firmness of character, noble actions, and love for one’s fellowmen. He was describing his own mother, his first teacher. If the women who raise their children have the mentality of a slave, then the country will never be honorable nor prosperous. “As long as the mother is a slave, all her children can also be enslaved.” He encouraged the 20 young ladies of Malolos to proceed along the path they had already begun. “If the Filipino woman will not change, she should not be entrusted with the education of her children. She should only bear them. She should be deprived of her authority in the home, otherwise, she may unwittingly betray her husband, children, country, and all.” Rizal had such wise and timeless words.

Luminous

Oil on canvas, 3 ½ feet x 3 feet

Salida de Frailes

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 6 feet

The signing of the Treaty of Paris, which effectively transferred the sovereignty of these Islands from Spain to the United States of America, was believed by some to have signaled the end of the frailocracy in the Philippines. This HOCUS painting shows the friars leaving Filipinas for

Madre España. But have they really left? Truthfully, that question calls for a yes and no answer. Yes, because theoretically they have been replaced by the missionaries of the new colonizers especially after they were forced by the American civil government to sell their vast friar landholdings. But 333 years of Spanish colonization led by the friars and Spanish civil and military authorities would be impossible to eradicate, as starkly illustrated by HOCUS paintings still hanging on the walls symbolizing the continuous dominance of the friars even after their alleged departure. In fact, even after the Spanish-American War was officially ended, the friars were still in firm control of their schools, churches and the prime lands which they refused to surrender to the American government.

Salida de Frailes

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 6 feet

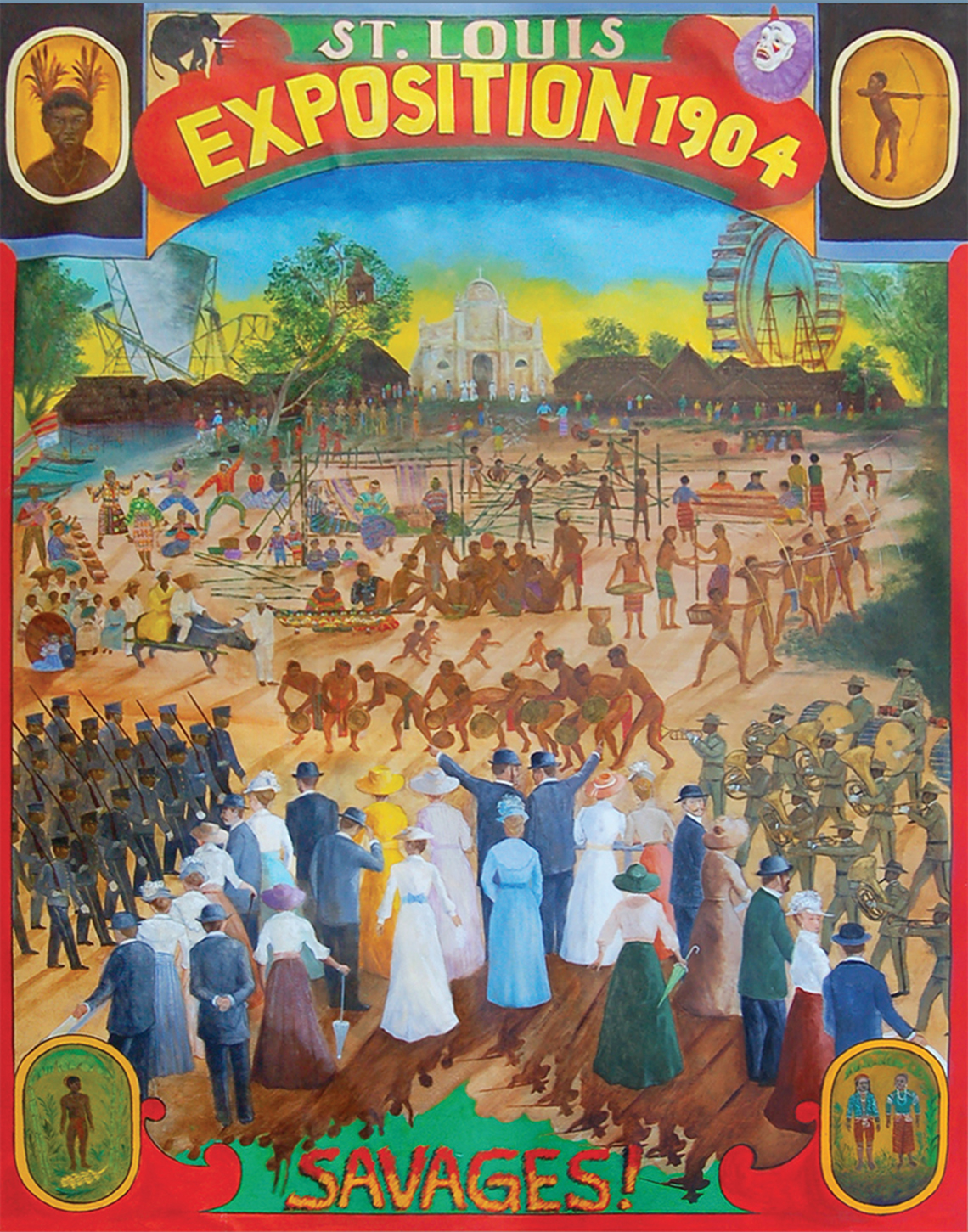

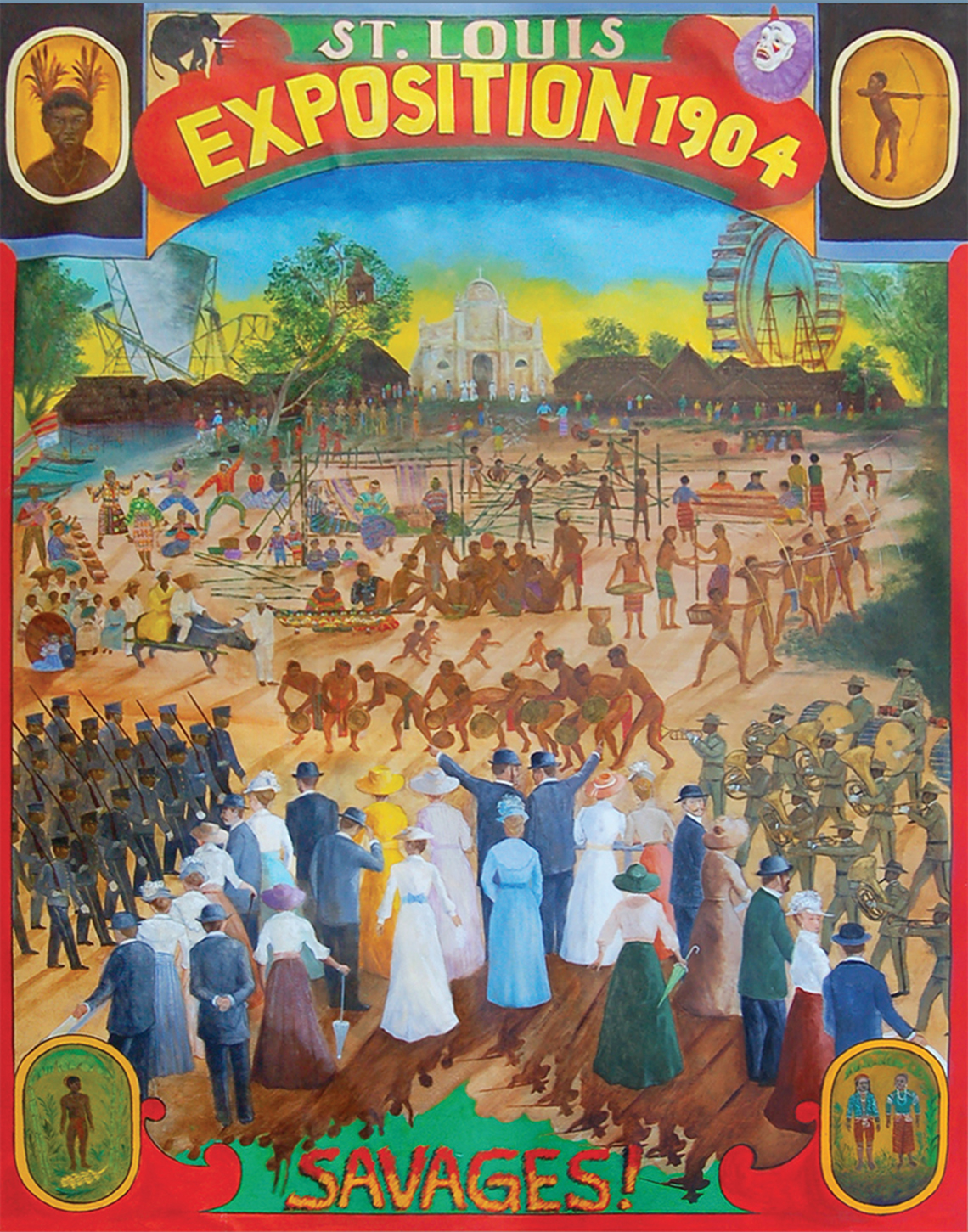

Savages on Display

Oil on canvas, 7 feet x 5 ½ feet

The St. Louis World Fair of 1904 was organized to commemorate the Louisiana Purchase of April 13, 1803. Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte of France needed money to finance his wars and the United States of America, with President Thomas Jefferson at the helm, wanted to expand its territory. For the sum of $15 million, the United States of America purchased New Orleans and the Louisiana Territory, a total of 827,000 square miles.

The USA doubled the size of its territory at the expense of the Cherokee nation and other Indian tribes who used to live in France’s former territory. Pres. Jefferson mercilessly drove all the Indians out. The main attraction of the World Fair was the “Philippine Reservation” which was constructed in front of an artificial lake across the “American Indian Reservation.”

It was William H. Taft, civil governor of the Philippine Islands, who saw in the St. Louis World’s Fair the opportunity to highlight the savageness of the Filipino and why he had to be “civilized” with a repeating bolt action rifle—the Krag. The Philippine Reservation was constructed for “ninety-four Igorrotes, eighteen Tinguianes, thirty-four Negritos, eighty Visayans, forty Samal Moros, thirty-eight Lanao Moros, five tree-dwelling Moros (sic), four Mangyans.” There were also two midgets, a man and a woman, for a freak show. Igorots were made to butcher and eat dogs every day.

Scantily-dressed women without upper garments were made to perform their traditional dances while male warriors with loincloths did their war dance routine with the clanging of gongs and ganzas.

Also on display at the World’s Fair were two battalions—400 Philippine Scouts, and 300 Philippine Constabulary soldiers. All of them were quartered separately. Like the Spaniards before them, the Americans divided the soldiers along tribal lines. A Major Carrington was selected to organize a battalion. He had seen action in Samar where he pacified Filipinos with the Krag. He was placed in command of six companies of Philippine Scouts but was ordered to select only four companies for the World’s Fair. Each of the four had to be composed of different “tribes.”

The Fourth Macabebes under Lieutenant Reese, the Twenty-Fourth Ilocanos under Lieutenant Dougherty, the Thirtieth Tagalos commanded by Lieutenant Dvorak, and the Forty-Seventh Visayans with Lieutenant King as commanding officers. In addition, nine Moros were enlisted. They came from the Moro Province of Mindanao and were made to wear the fez, unlike the rest who wore the khaki forage cap as headgear.

This HOCUS painting was purposefully made to look like a circus poster, because as far as the Filipinos were concerned, the St. Louis World’s Fair was nothing but a humiliating circus. The Filipinos were presented as savages to the twenty million people, the majority of them Americans, who visited the Fair in 1904. The refinements of the “Manila Building” hardly left a dent on their collective memory; only the “savage” dog eaters, the

half-naked dancers and weird tree dwellers left indelible marks.

To this day, Americans still ask whether Filipinos have tails or live in tree houses. After the St. Louis World’s Fair, Filipino minorities continued to be displayed in various world fairs and carnivals.

They were shipped to the Lewis and Clark Centennial (1905), American Pacific Exposition (1905), Portland Oriental Fair (1905), and the Jamestown Tercentenary Exposition in Virginia (1907). “SAVAGES!” gasped those who watched with morbid curiosity and delight. In 1908, the Philippine Assembly passed two laws which stipulated that no tribal people should be exhibited except those who were customarily fully clothed; in 1914, another law penalized anyone who would exploit and exhibit tribal people with a fine of $5,000 and imprisonment of not more than five years. When the Philippine Resident Commissioner in the USA, Manuel L. Quezon, was the guest of honor at “Philippine Day” at the San Francisco Exposition, he said in an interview that during his many trips across the USA; “I have been saddened to learn how many misapprehensions exist here as to the real conditions in the Philippine Islands due to the exhibition of the native Igorrote village at the St. Louis Exposition ten years ago.”

As late as 1931, no less than the US War Department created an “Igorrote Village” at the Paris Exposition, and, ignoring the existing laws, wanted to send Filipino highlanders to France. Adding insult to injury, the US War Department demanded that the Philippine Assembly appropriate $50,000. Our legislators were livid, so the American exposition committee had to use wax figures instead.

SAVAGES! Somebody whispers in the crowd. But carefully look at the shadows cast by the audience. It shows in horrible detail through created shades and images the atrocities committed by the American soldiers to pacify these Islands.

Savages on Display

Oil on canvas, 7 feet x 5 ½ feet

The Prayerful Pagan

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

The monk draws a first card, it is El Mundo (The World).

The card shows the Carriedo Fountain and the indios occupying its lowest tier, in representation of what life was like during the period of Spanish rule. The religious orders that evangelized and pacified the islands occupy the second tier of the fountain.

The Spanish coat of arms or escudo, symbol of the Patronato Real, the royal patronage, occupies the finial of the fountain.

The second card drawn is El Juicio (The Judgment). It depicts the Last Judgment, the Juicio Final. The carta shows the natives on the way to the Final Judgment at the magnificent cemetery of San Joaquin in Iloilo.

One can count twenty steps to the marvelous capilla. According to local legend, these steps were made by the women of the town. The capilla is where the final rites are conducted before the dead are laid to their resting place and their souls sent to wherever they are awaited in the afterlife.

The third card has been drawn and is about to be laid out. Its reverse side shows a friar wielding a crucifix as if it were a sword. Around the figure are the words:

La primera te dice lo que parece ser, la segunda demuestra porque la verdad se oculta y la tercera vislumbra la pura verdad.

The legend written in Spanish teaches the novice how the cards are played. The words translate to:

The first tells you what appears to be, the second tells you why the truth is hidden, and the third tells you the truth.

But wait. Maybe we should examine the painting with better care. Is he truly a monk and a follower of Christ? The clue may be found in what he holds in his hand. It is a subha or misbaha—Muslim prayer beads.

Each bead engages the supplicant in a conversation with God. The Muslim prayer beads are like the rosary of the Christian faith and shuns thoughts and forbids thinking since everything is just a matter of mechanical repetition of words whose authorship has long been lost. Be that as it may, the seated figure is not a bible-reader but that of the Koran. He will not die and depart for a murky and painful place to atone for sins which the friars say he has committed. He is immune from the dominion of a Christian hell. He is not of the Faith.

The Prayerful Pagan

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

The Floating Fiddler

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

The fiddler on the roof first appeared in the stretched-out canvas of the then 21 year old Marc Chagall in St. Petersburg.

He said that the idea of the fiddler on the roof came from a childhood memory of an old man in his native Russia, who disappeared one day and was later found on top of a roof eating carrots. Perhaps the old man was in dotage or perhaps he just wanted a change of scenery or maybe the roof offered him a strange refuge from his home underneath.

This HOCUS painting shows a woman with a fiddle dressed in native garb. Above her are the changing faces of the moon symbolizing the march of time. For is it not true that man used to mark the months by moon phases before calendars were invented?Below are words which makes her a part of all that is alive in this world. Translated from Spanish, it says: “It is now time to work.

The Floating Fiddler

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

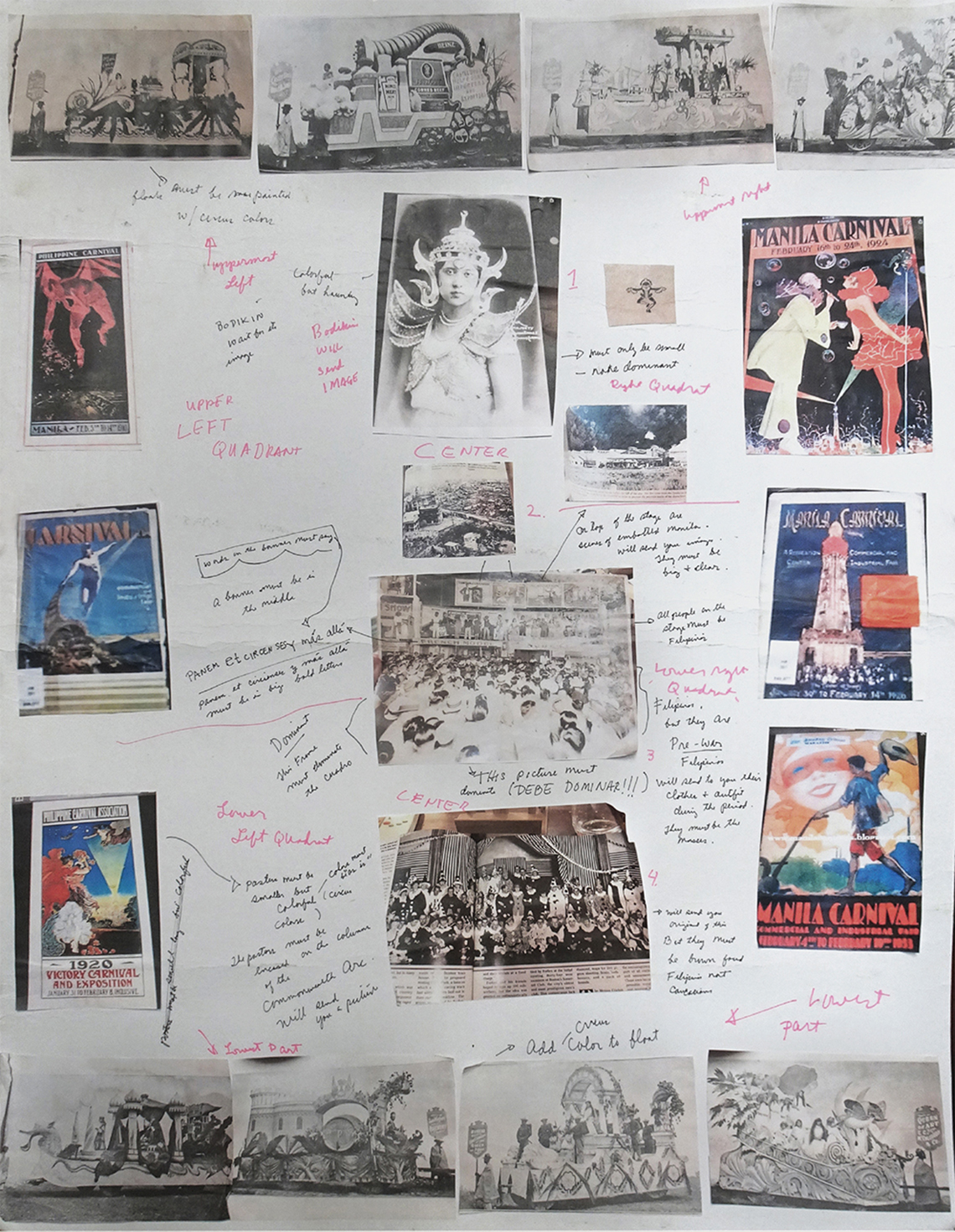

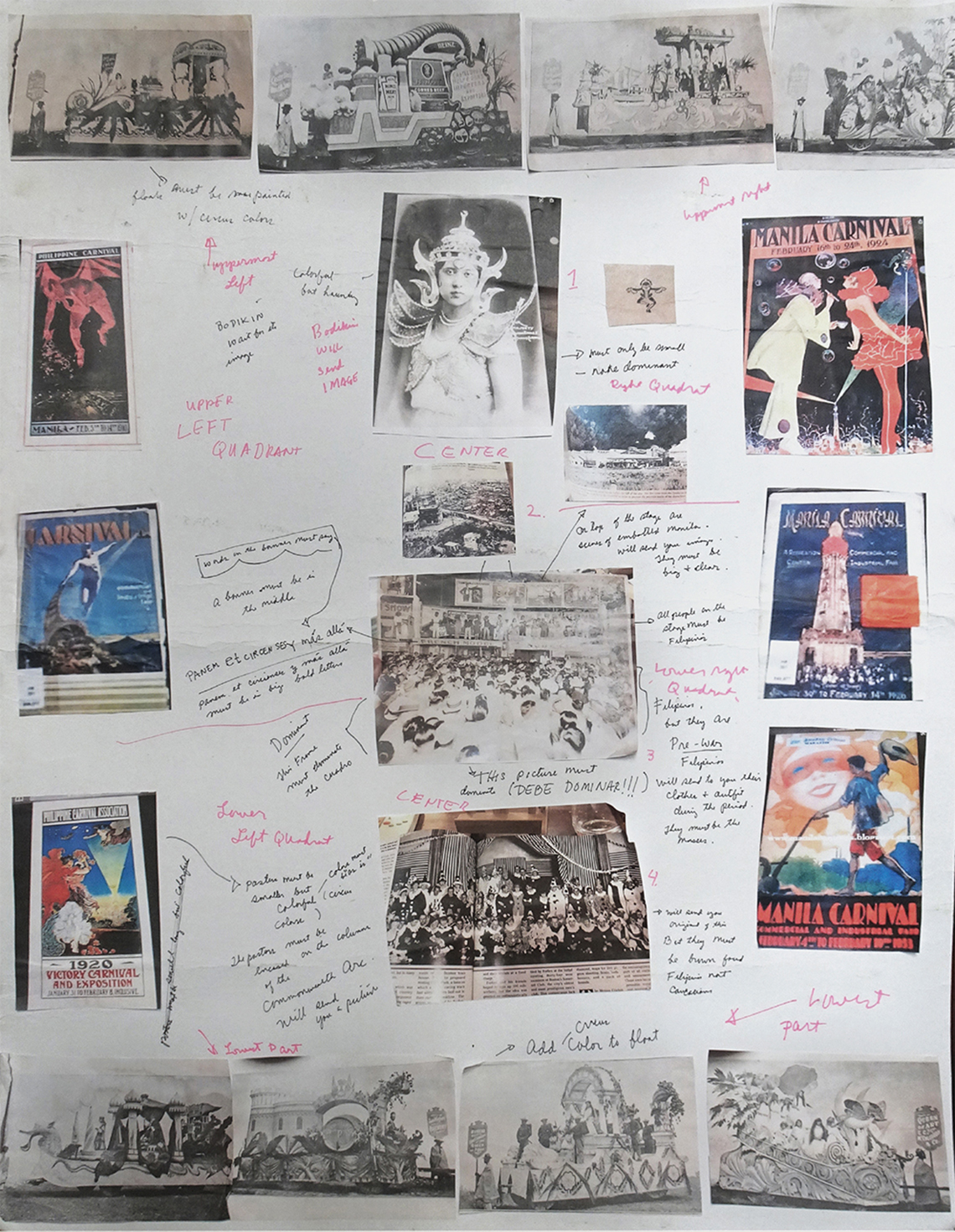

The Making of Hocus

Cardboard, 4 feet x 3 feet

A HOCUS painting begins and ends with an idea. The idea is historical and tells us the story of our people. The idea may be about a man, an event or even about a thing upon which history has bestowed a special meaning. The idea is conveyed to the painter and then transformed into a boceto or a study after instructions are given on how the idea should be turned into a work of art. It is then critiqued, changed, checked, and altered before it becomes a finished painting on canvas or work done on wood.

The boceto which is painted on canvas is then signed with the anghel de cuyacuy with the word “Primer” underneath to indicate that it is the boceto or the first state before an actual painting is made.

If the subject of the HOCUS painting is difficult, especially during the pandemic where face-toface meetings have become impossible because of the restrictions and lockdowns, I make a collage of what I want Custodio to paint with particulars as to size, color and the reasons why I want the subjects to be shown on the painting. The pictures in the assemblage are not to be copied—their purpose is to convey the idea of what needs to be done.

The painting subject of the collage shown here was unfortunately never executed because the painter Guy Custodio wanted to live near the beach to escape the onslaught of the virus (I told him that saltwater kills viruses and bacteria for which reason numerous leprosaria existed during the Spanish period around Guam and other islands in the Marianas).

The pictures speak of the ideas that I wanted him to paint. It shows posters of the Manila Carnival, a festival that existed during the period of American occupation. It was designed to entertain us, like a circus. It was meant to discombobulate, to make us think how wonderful it is to be the little brown brothers and sisters of the big white man. It shows the floats of the carnival and the beautiful posters advertising the exposition.

I wrote explanations on its face since I cannot personally talk to Custodio because of the pandemic. The upper portion of the collage shows a picture of Miss Manila Carnival.

Below her, in ascending order, is a picture showing white Americans wearing clown costumes, a local stage performance with hanging posters which depicts scenes from the Battle of Manila and the massacred Filipinos who perished during the battle. The message is obvious—the only justification for colonization is exploitation and in times of war, the colonized subjects become cannon fodder.

The Making of Hocus

Cardboard, 4 feet x 3 feet