About the Hocus Paintings

HOCUS is an acronym of the surnames of Saul Hofileña Jr., the intellectual author of the thought-provoking collection, and Guy Custodio who collaborated by painting Hofileña’s visions of Philippine colonial history. In the preface to the HOCUS III (Juicio Final) book Custodio wrote, “… I took instructions from Saul on how a painting should be done, the subject of each painting, the color schemes and all other matters that needed to be done, in order to transform paint and canvas or wood into a HOCUS painting.”

Each HOCUS painting is signed with an icon, Hofileña’s brainchild which he calls Anghel de Cuyacuy. The Filipino angel is seated on a bench, jiggling a leg nonchalantly (a typical Pinoy mannerism) while reading a book. He is an angel ready to battle ignorance and superstition, as well as Satan’s evil minions, according to Hofileña.

HOCUS enjoyed two hugely successful six-month exhibitions on April 18, 2017 to October 29, 2017 and September 15, 2019 to March 15, 2020. Six large paintings from HOCUS I are on permanent display at the East Wing Hallway Gallery at the 4th floor of the National Museum of Fine Arts which includes the thought provoking “La pesadilla” (The Nightmare). Also permanently exhibited along the Second Floor Northeast Hallway Gallery at the National Museum of Anthropology are five HOCUS paintings that were part of the Quadricula (HOCUS II) exhibition.

Gemma Cruz Araneta

Curator, Hocus I and Quadricula

HOCUS II

The Hofileña-Custodio paintings exhibited at the National Art Gallery of the National Museum of the Philippines on September 15, 2019 to March 15, 2020

The Spanish Quadricula

Oil on canvas, 3 feet x 5 feet

In this HOCUS painting, one sees a conquistador and a friar laying out a network of squares in a grill pattern for Intramuros, with the aid of celestial beings. Angels descend upon Forth Santiago bearing the symbols of conquest. From left to right, an angel carries a sash with the names Legaspi, Salcedo, Goiti, Lavesares, the four pillars of the colonization. Two angels descend from the heavens with the Spanish sword and crown.

Angels carry the unique Spanish letter Ñ, a laurel wreath of victory, a skull to symbolize mortality, the symbols of the Franciscan, Jesuit, Recollect, and Dominican Orders. An Oriental-looking angel waves the baraja española, proof of the predicament of the Chinese who in part financed the construction of the walls from the taxes on playing cards they sold.

The Spanish Quadricula

Oil on canvas, 3 feet x 5 feet

Permanent Exhibit, National Museum of Anthropology, Republic of the Philippines

The Colonization of the Mind

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 5 feet

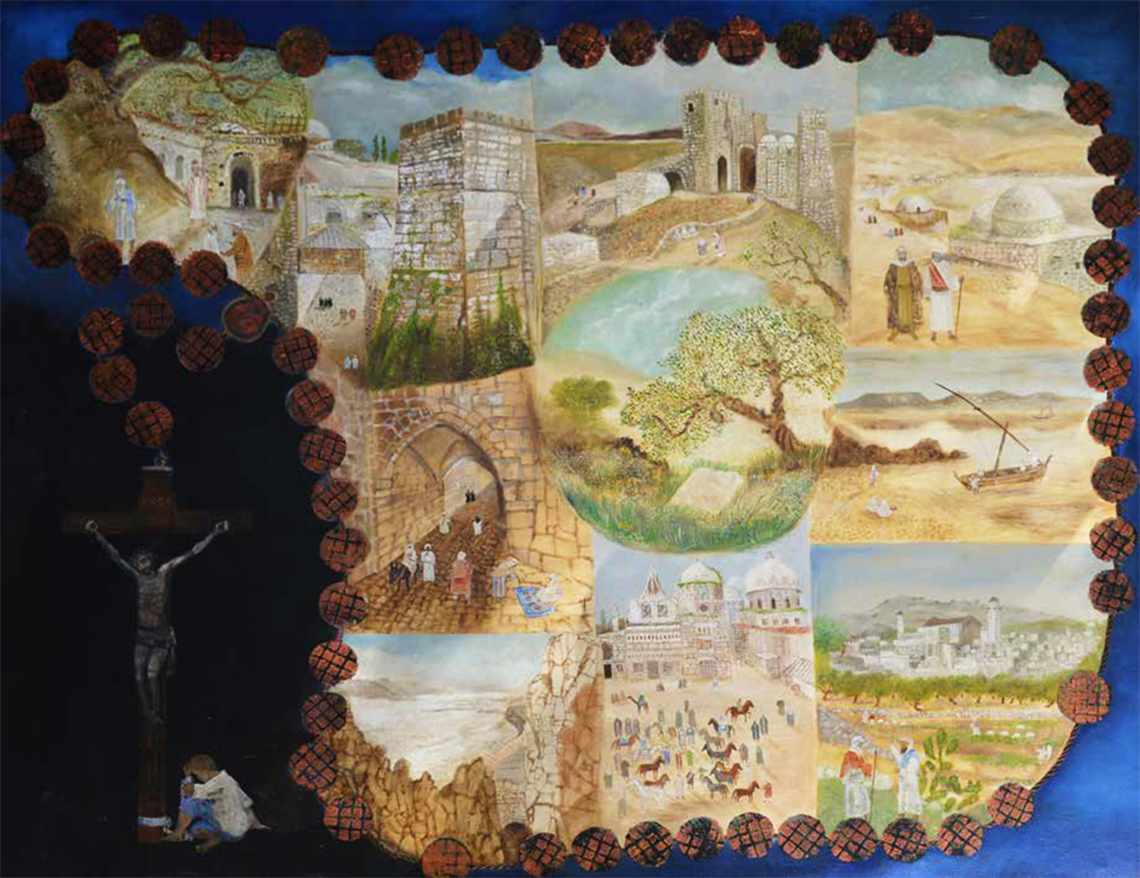

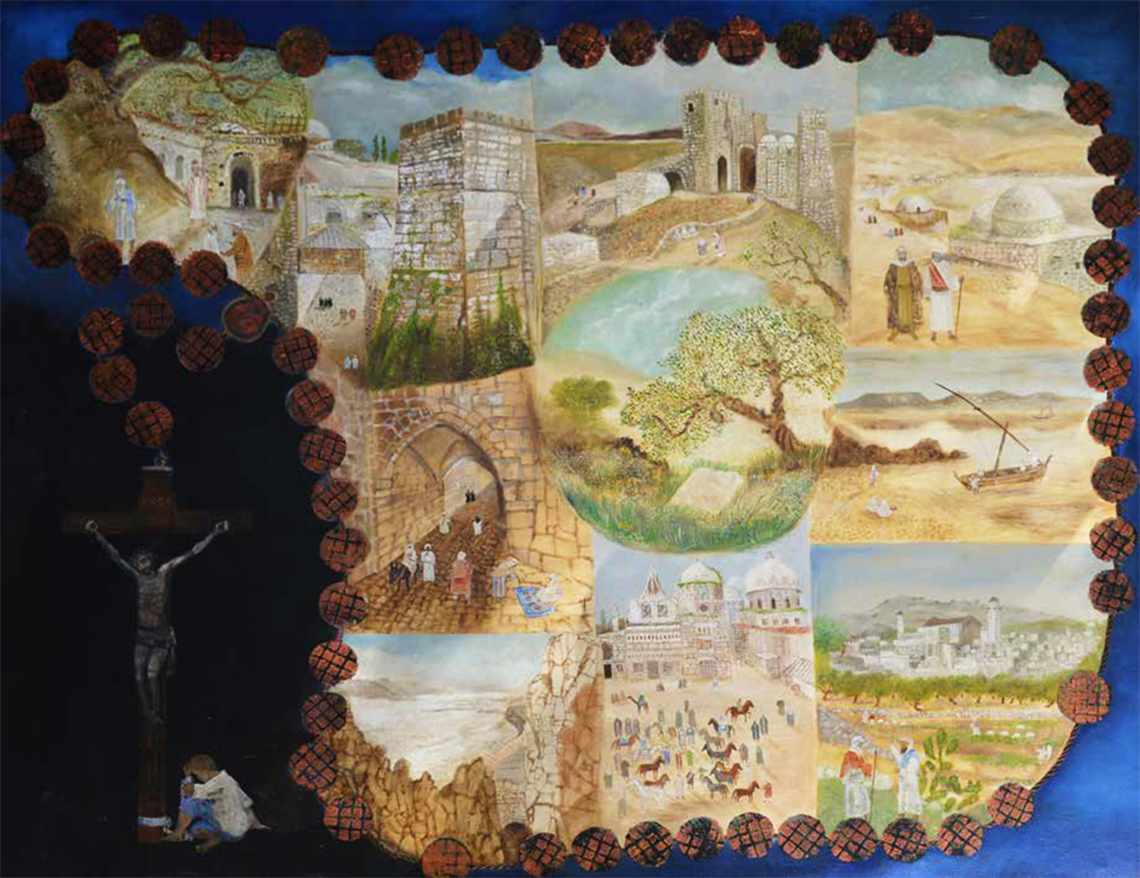

Because of the evangelization of the indio, he was transported to ancient lands with strange names like Jerusalem, Damascus, Aleppo, Bethlehem, inhabited by men with flowing-robes and beards, riding intractable dromedaries, living in houses with strange architecture and practicing strange customs. By dint of proselytization, the indio was colonized by a religion that came from the Middle East, secretly transported to present day Italy, adopted by Rome as the state religion of the Roman Empire, thanks to Emperor Constantine; thence to Spain and from Spain through Mexico, carried by wind ships to the Philippines.

The fact that during Holy Week Filipinos are made to wear Jewish clothing popular during the time of Christ and made to sport false beards held in place by rubber bands or strips of garter and grown men are made to wear the uniform of Roman soldiers of the emperor’s legion in Marinduque, proves that the Filipino mind’s colonization was a complete success.

The Colonization of the Mind

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 5 feet

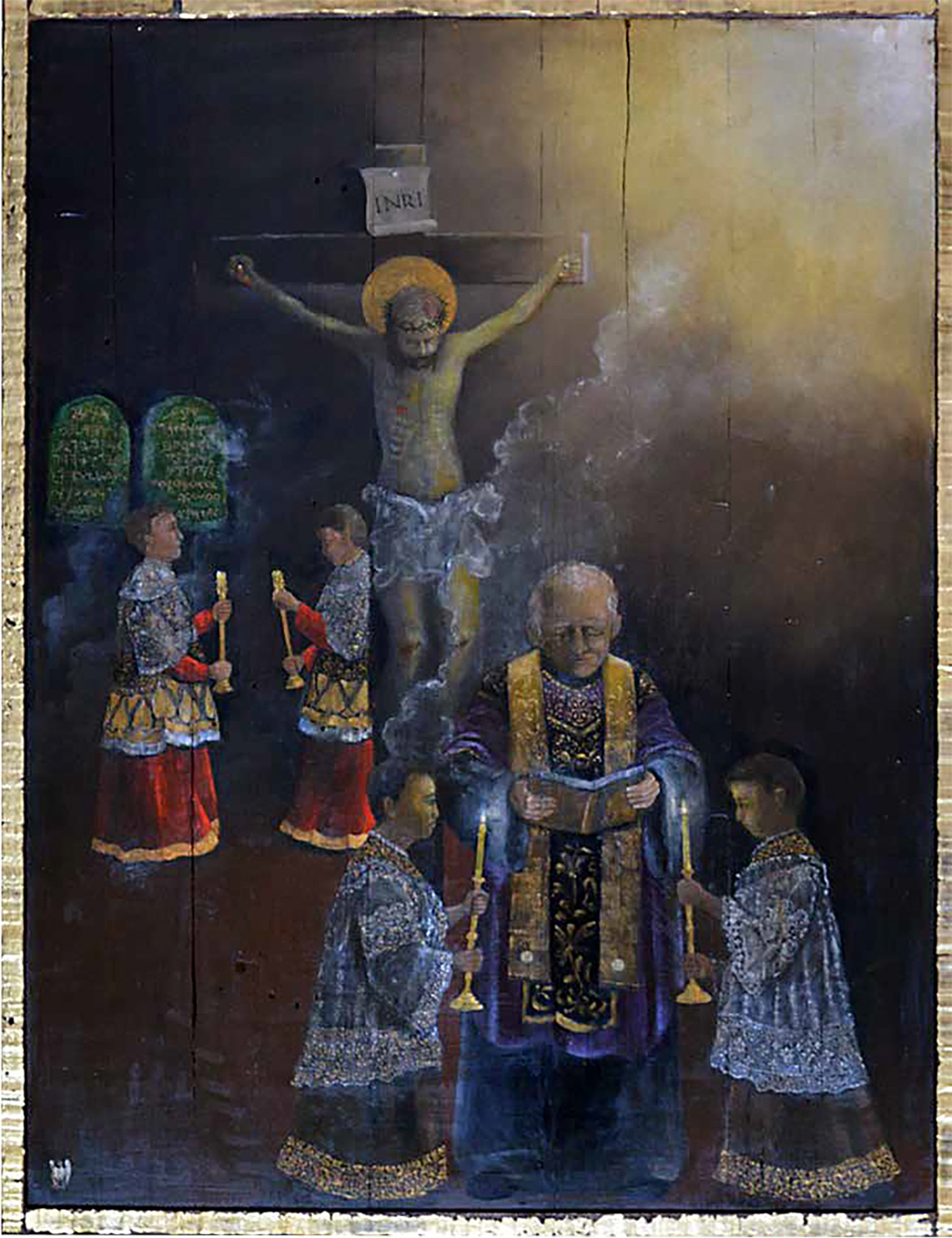

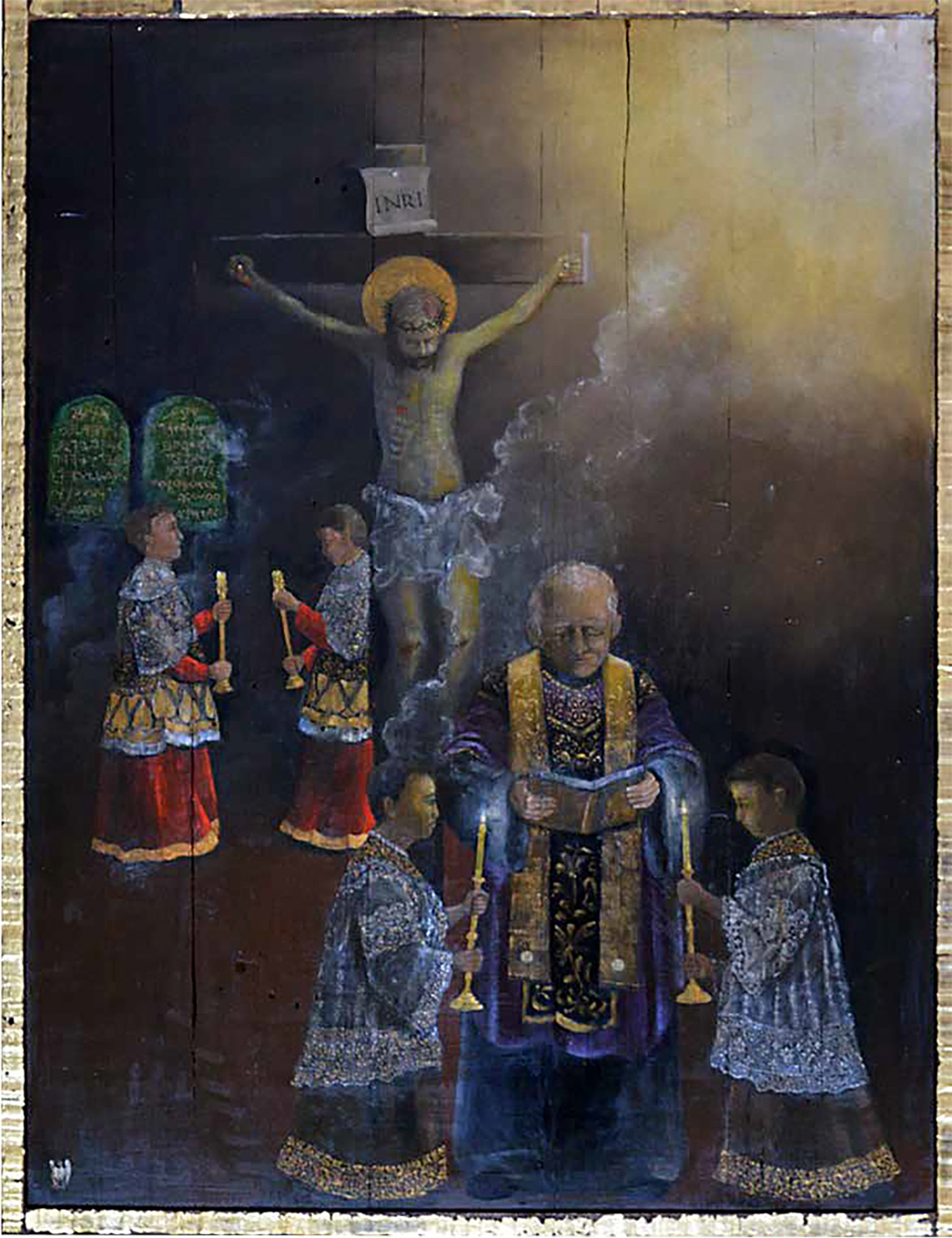

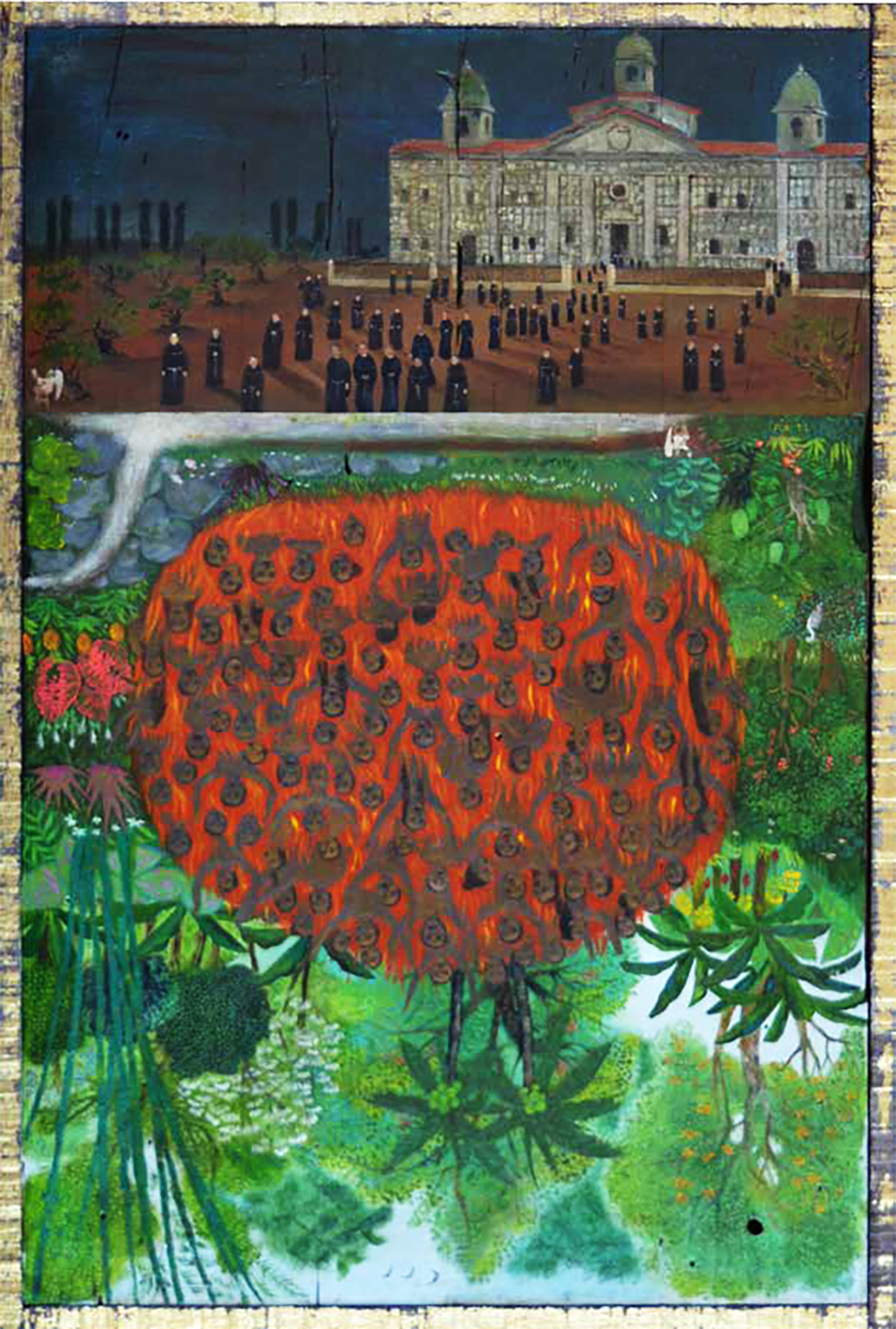

The Origin of Faith

Oil on wood, 4 feet x 3 feet

Jesus Christ separated the two great Faiths—Judaism and Christianity. If not for Jesus Christ, every Christian would be practicing the religion of the Jews. The Old Testament is actually the history of the Jewish people and their religion. Read the Old Testament and you will learn about Elijah, Lot, Abram, the clans of Pallu, Hezron, Hanoch, and places like Peor, Moab, Ammon, Beth Jeshimoth, the Jabbok River. It speaks of people and places with strange sounding names which many Filipinos cannot even pronounce correctly.

The idea for this HOCUS painting came to me while waiting for diplomas to be distributed in the school where I teach and governed by monks. The significance of the candles were explained to me by a resigned priest who carry a Castilian name—Capellan—which means chaplain in Spanish.

In the foreground of this painting, a priest standing between two sacristans is reading the Gospel according to St. Luke from the New Testament. Each sacristan is holding a lighted candle to illumine the pages narrating the life of Christ. Behind the priest is the scene of the Crucifixion; Jesus Christ in agony, crowned with thorns, is about to breath His last. Behind the towering Cross, there are two more sacristans, but unlike the first two, their candles are extinguished to hide the origin of the Christian faith. The tablets of the Ten Commandment which God gave Moses on Mt. Sinai glow in the background. All that represents the Old Testament, Jesus Christ was the Great Separator, the demarcation line between the Old and New Testament, the great divide between Christianity and Judaism.

The Origin of Faith

Oil on wood, 4 feet x 3 feet

El fin del mundo

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 8 feet

The HOCUS landscape on the next page is reminiscent of a painting of Manila made by Fernando Brambila which he painted in 1792. He was part of Alessandro Malaspina’s scientific expedition that left Cadiz in 1791 to visit Spanish colonies in the Americas and Asia; they passed by the Philippines in 1792. The fluvial procession on the Pasig River is apocalyptic. Each religious Order is represented by a float with their respective patron saints and emblems which are being toppled over by waves. What purpose would these graven images serve if the end has come?

As the faithful gather along the Pasig, they are horrified at the sight of their favorite patron saints hurled into the river by a mysterious force. Cries of “It’s the end of the world” are deafening; “Save our saints!” Terror and panic reign.

El fin del mundo

(The End of the World)

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 8 feet

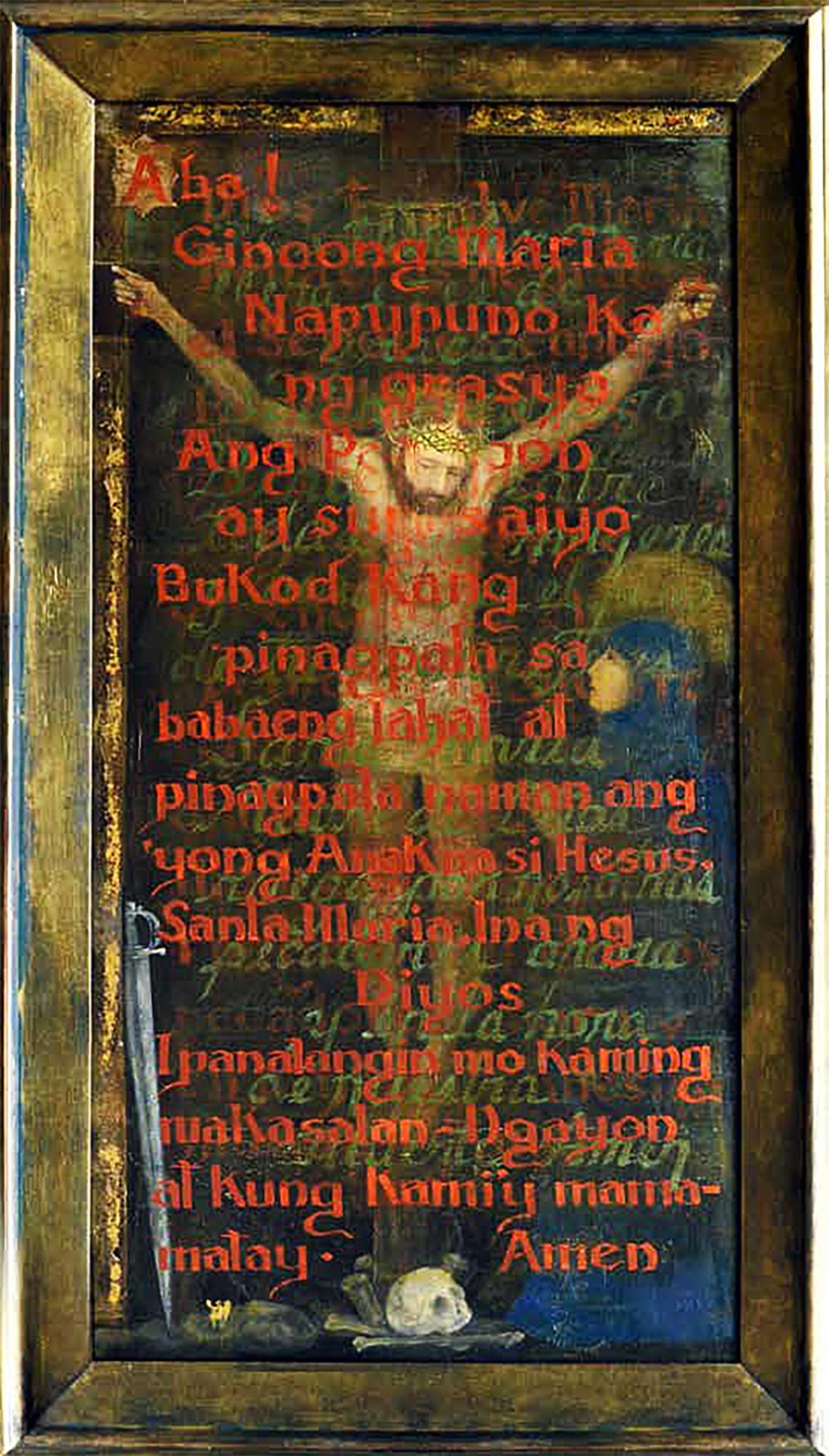

The Philippine Palimpsest

Oil on canvas, 3 feet x 2 feet

In the Middle Ages, monastery scribes laboring in medieval scriptoria oftentimes scraped off the words written on animal parchment so that those expensive leather sheets could again be used. There was often a shortage of animal parchment. This recycled manuscript page is called a palimpsest. Sometimes, the palimpsest would yield its secrets as the words previously erased become visible again. In the Philippine palimpsest, the

Tagalog equivalent of the “Hail Mary” is superimposed on the Spanish version, an overlay written in blood red script, signifying the bloody conquest of these islands, in the name of religion. The original Castilian

script of the prayer is accidentally exposed and unmasked for all to see.

The Philippine Palimpsest

Oil on canvas, 3 feet x 2 feet

The Forever War

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 8 feet

The war in Mindanao between the Spaniards and the Moros first erupted in the 16th century, but it continues to this day, more than a century after the Spaniards were compelled to leave our country.

In this HOCUS painting, the armies of the Crescent and the Cross are about to collide head on. On the left, Buraq, the steed of the prophet Muhammad, pulls a wagon-load of warriors, a Moro angel holds the reins while Death, the grim reaper, steadies the horse that once flew the Prophet to Jerusalem. On the right, a wagon-load of Tagalog and Visayan soldiers trained by the Spaniards to fight the Moros rush towards their sworn enemies. They are also escorted by Death. The outcome of the battle is foregone. Death holds the reins of both wagons. From above, Christian and Moro angels, like frightful Valkyries, dive towards their respective wards to take their souls to the Paradise of their chosen faith.

Even celestial bodies are engaged in this eternal war. The sun and moon battle for supremacy. The sun covers the moon in a reverse eclipse; the moon becomes a crescent—the Crescent of Islam—while the sun converts into the overpowering Lumen Christi—the light of Christ—the symbol of Jesus Christ.

The Forever War

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 8 feet

La Quinta

Oil on canvas, 8 feet x 16 feet

To effectively implement the “divide and conquer” strategy, the Spaniards banded natives of one region together into sections and battalions which were sent to other regions of these islands. Thus, those from as far north as Cagayan were sent south to Tayabas; the Kapampangans of central Luzon, a particularly warlike people, were sent to occupy different parts of the archipelago. They implemented this system in the organization of the Guardia Civil and the other native auxiliaries of the Spanish armed forces. In certain periods of turbulence, the Ilonggos were sent to Cavite, those from Malolos to Lallo, the then capital of Nueva Segovia and the men of Tayabas were even sent to Cochin China.

This allegorical HOCUS painting shows that during the colonial period, the Church and State (represented by a military officer and a friar) jointly took charge of training native boys in the art of military warfare. The result of that rigorous discipline is shown below the painting—native troops brandishing different campaign flags, ready to fight and kill their own kind, for the glory of Spain. To this day, we are suffering the aftermath of that insidious “divide and conquer” rule.

La Quinta

(The Fifth)

Oil on canvas, 8 feet x 16 feet

Los recien llegados (The Recent Arrivals)

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 8 feet

Members of the five religious orders who came to Christianize the Philippines are presented in this HOCUS painting with pixelized forms breaking up in fragments. They appear to be blessing the viewer when in fact, with their fingers, they are telling us the chronological order of their arrival in this archipelago. From the left, the Augustinian friar signals with his finger that his Order was the first to arrive, they came with the Adelantado Miguel Lopez

de Legazpi, a former mayor of Mexico, in 1565. The Franciscan next to him shows the number two with his fingers since his Order was the second group of missionaries to arrive in 1578. The Jesuit, in the middle, indicates that his Order was the third to reach these shores; two Jesuit priests were with Bishop Domingo de Salazar when he landed in Sorsogon in 1581. A Dominican forms the number four with his fingers; the Order of Preachers came ashore in 1587. The last to arrive were the Recollects, who unladed in 1606.

Los recien llegados

(The Recent Arrivals)

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 8 feet

Swords of the Cross

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

In this HOCUS painting, the Christian Cross is formed by a Spanish and a Roman sword. The latter symbolizes Rome’s vital contribution to the theological underpinnings of the Spanish Empire. What a formidable weapon, a Cross forged by two mighty swords, the Spanish and the Roman. In this HOCUS painting, the Cross is a terrifying centripetal force, symbol of the Spanish conquest that sucked in its whirling vortex everything and everyone around it. They were the nameless indios, objects of subjugation by the Kingdom of Spain and the Church of Rome.

Swords of the Cross

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

Permanent Exhibit, National Museum of Anthropology, Republic of the Philippines

El arsenal de la fe

Oil on canvas, 3 feet x 5 feet

This HOCUS painting looks like a celestial stockholders meeting in an undetermined war room where an intimidating assembly of archangels, in shining armor, have direct eye contact with the viewer. Presiding over the meeting at the head of the table, a Franciscan friar presents one of the most efficacious weapons in the arsenal of the Catholic Faith—the religious procession. The dramatic spectacle of a religious procession was designed to lure the pagan natives from their hillside ricefields to the newly erected towns where they could forget their pagan practices as they were converted to the new Faith.

El arsenal de la fe

(Arsenal of the Faith)

Oil on canvas, 3 feet x 5 feet

Polos y servicios

Oil on canvas, 3 feet x 4 feet

This HOCUS painting immortalizes the thousands of nameless indios who rendered force labor for more than ten years to construct this magnificent church, with twin belfries and seven anti earthquake buttresses on each side, it was finally competed in 1797. Carpenters, masons and bricklayers, hewers of wood and stone, Atis, the earliest inhabitants of Panay are also seen in this painting. Look for women breaking eggs, separating the egg whites used as binders for the church stones. Sculptors, painters, Capiz-shell artisans all rendered tireless service to Church and State. Do you see St. Christopher with the Christ Child on his shoulder walking towards the church? Massive like fortresses, intimidating yet mystical, these colonial churches required a tremendous amount of forced labor which became one of the principal grievances that led the indio to demand freedom from Spain through force of arms.

Polos y servicios

Oil on canvas, 3 feet x 4 feet

Ang Pasyon

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

In this HOCUS painting, one sees the suffering Christ on His way to Cavalry painted in a Philippine setting. On the center of the painting, a Filipina, who had begun reading the Pasyon since childhood, and continued to read it through adolescence, adulthood, old age, up to the last of her days. Also, at the center is a Jesuit who reminds the viewer that the tagalog Pasyon was printed by the religious order. Both his hands bear Christ’s stigmata; he is holding the plant called the “crown of thorns.”

In the upper portion of the HOCUS painting is a gruesome scene depicting the crucifixion of Christ showing Roman soldiers who look like the Moriones of Marinduque. There is a black rainbow arching over the crucifixion, portending the outbreak of religious conflicts after the death of the Only Begotten Son of God.

The Tagalog words around the painting are those of Aquino de Belen, the printer of the Jesuits. There are Castillian words as well, like tinieblas referring to the period of darkness, the anticipating sign for the death of Christ; or it may also refer to the dichotomy of the Lenten season, a time of the darkness of sin and the light of salvation. From twelve noon to three in the afternoon, the priest intones the Seven Last Words of Christ. At the exact hour of 3 o’clock in the afternoon, the Faithful make noises mimicking the sounds of the lightning storm that took place when Christ was dying on the cross. Thus, wooden clogs are hammered on the ancient adobe stone walls of the church; there is wailing and screaming and moaning, all in protest of the death of Christ. At exactly three o’clock in the afternoon everything stops. Silence reigns. The Son of God is dead.

Ang Pasyon

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

Lashes in the Name of God

Oil on wood, 5 feet x 4 feet

In the 17th century, it was found necessary to lash the natives in order to force them to go to church and attend the Holy Mass. Lashing was not only excruciating, it was shameful. Some of the friars of the religious Orders lashed even women and girls with a cat-o’-nine-tails, or latigo ruso, a whip with 9 strands knotted at the end, with thorns and metal nails, a veritable instrument of torture. Even in the presence of their husbands and fathers, females were whipped, and no one dated say a word in their defense. This practice of whipping the indio was especially prevalent in the

provinces.

In this HOCUS painting, a woman is seen being whipped inside a church, a practice narrated by the Frenchman Le Gentil. As late as the latter part of the 19th century, the Englishman John Foreman observed that natives only go to church because it is a custom. That if a native does not have clean clothes he does not go to church. That the gobernadorcillo was required to go to mass and in some towns village chiefs were fined or beaten if they were absent from church on Sundays and certain feast days. Today, lashing and other corporal punishments are no longer meted as punishment for one’s sins, perhaps, the beatings may be the reason why people behave so impiously in Church, or have stopped going to Mass.

Lashes in the Name of God

Oil on wood, 5 feet x 4 feet

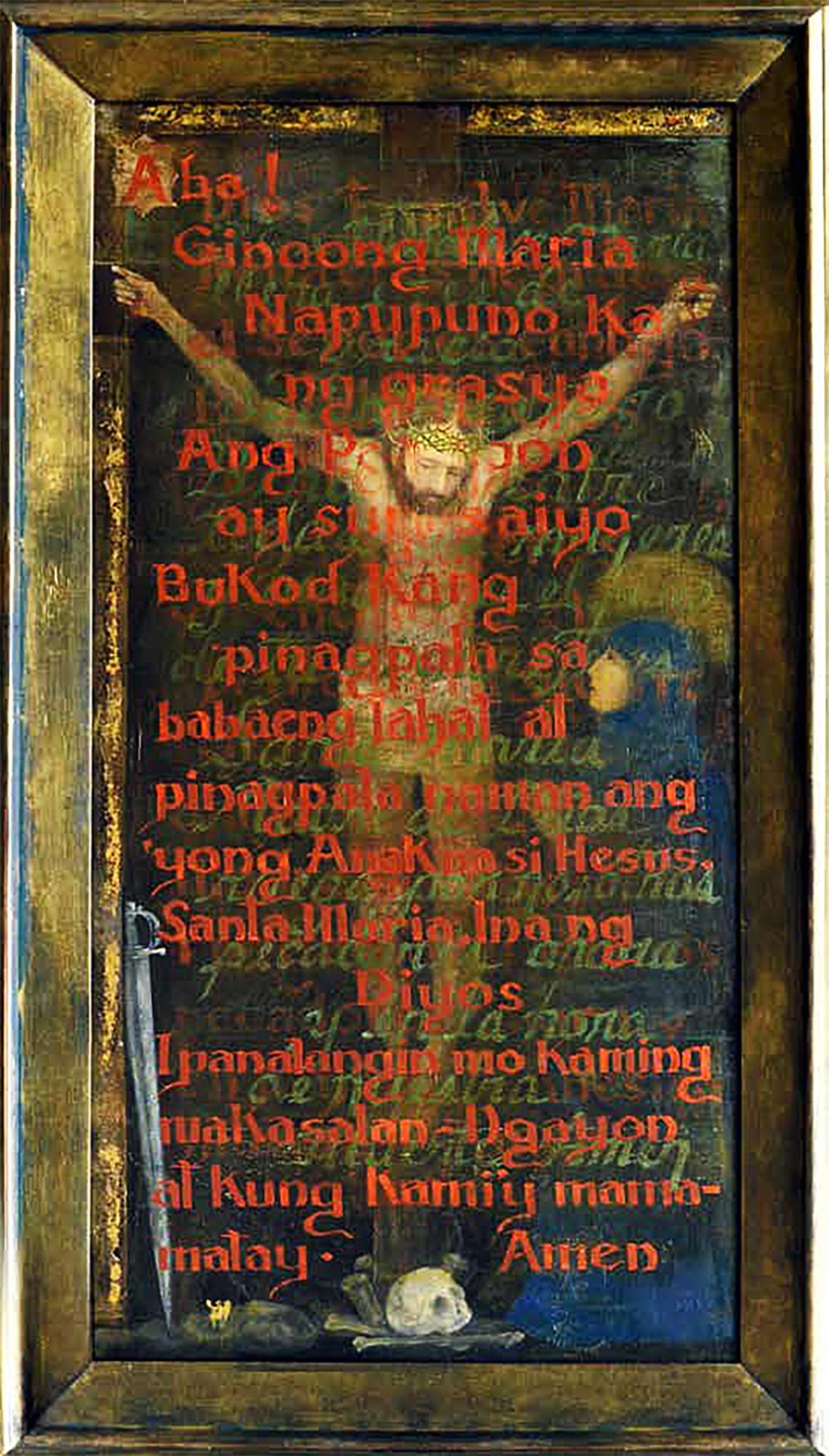

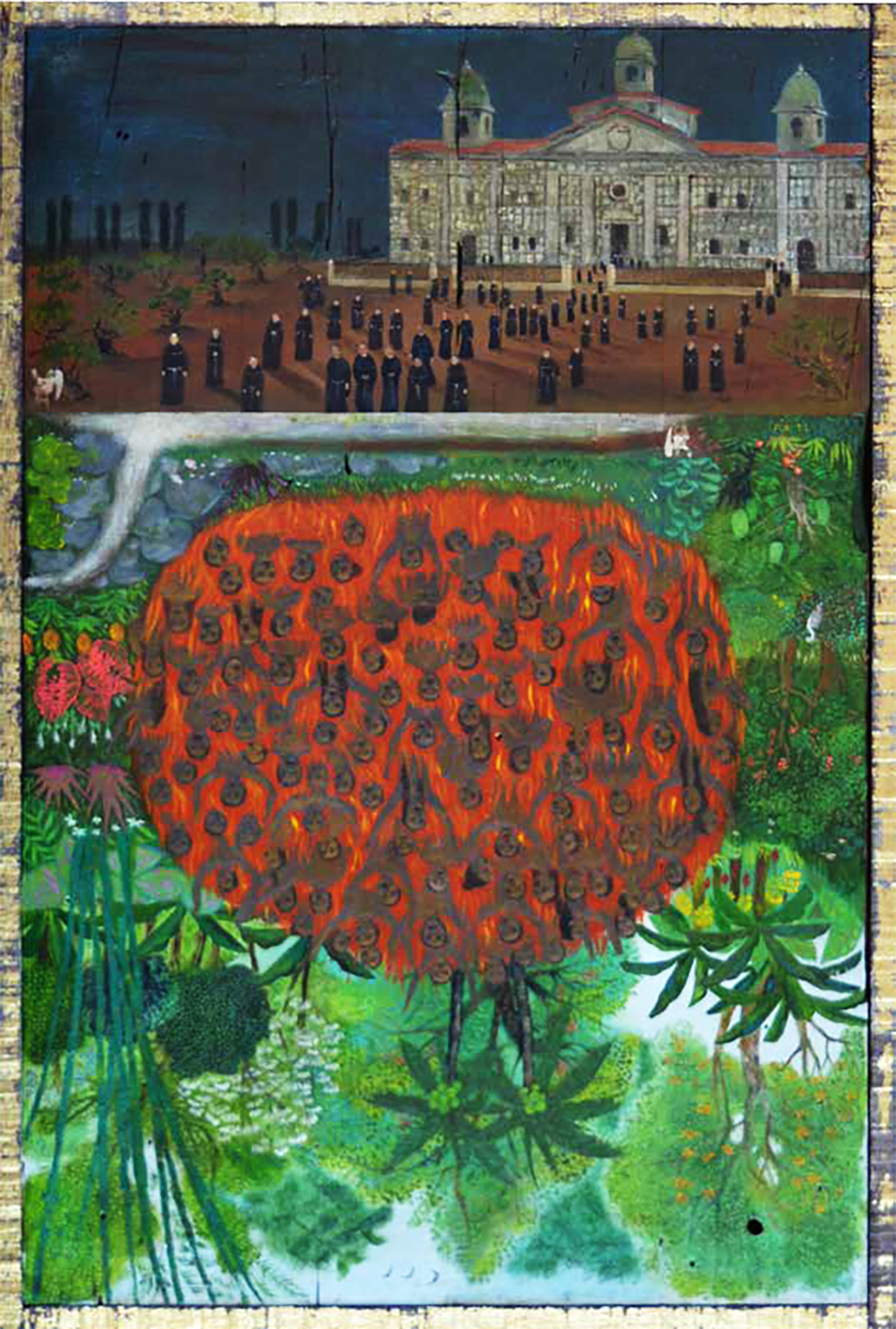

What the Friars Taught

Oil on wood, 4 feet x 3 feet

This HOCUS painting shows how life in these bountiful islands became hell for the natives; without having to go to Hell after death, they were burning in their tropical paradise for sins the friars said they had committed. Then as now, the fear of eternal damnation seems to be the persuasive means to compel obeisance to the Faith specially during the period of conquest when it was used to make the task of Christianization less cumbersome. The natives were thought to believe without question on the words of the priest. In a prayer book entitled “Pang Tauag nang caibigan Nang Manga Catolica” written by Padre Pablo Teisan, co-adjutor of the arrabal of Tondo in the late 19th century, there appears the following passage: “Dapat ca naming mag tanong sa bihasa mong confessor at sa canyang hatol ang loob mo ay iayon.” In the seventeenth-century, a Dutch visitor described Valladolid, the place in Spain where the Augustinians were educated and sent. He wrote that Valladolid was full of “… picaros, putas, pleytos, polvos, piedras, puercos, perros, piojos, y pulgas!” (… rogues, whores, fights, dust, stones, swine, dogs, lice, and fleas!)

Hell is not a place beyond death, it is a raging forest fire in this life, in a lush tropical paradise where natives are torched and burned as taught by the friars in order to protect and justify the oppressive colonial system.

Invert the painting and you will see Augustinian friars passing through the portals of the Iglesia de los Padres Agustinos in Valladolid, Spain, on their way to the New World, in the failed search for the Spice Islands they found this “tierra abundancia” or land of abundance instead.

What the Friars Taught

Oil on wood, 4 feet x 3 feet

At the Crossroads

Oil on canvas, 8 feet x 4 feet

The Holy Inquisition has disgraced the Visayan with the sambenito and coroza which will not be removed until he destroys his idols and renounces idolatrous practices. There are two colonnaded corridors in the Roman-style temple; at the end of the one on the left is the crucified Christ, the Son of God; the one on the right lead to the Likha, the god of his ancestors. Whom will he choose?

At the Crossroads

Oil on wood, 8 feet x 4 feet

The Three Mandarins

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 8 feet

On May 23, 1603, the Chinese Mandarins arrived with an impressive entourage of bailiffs, soldiers and retainers, carrying their seals of office. As if they were masters of the nascent colony, the Mandarins started to administer justice to those of their own kind. They had a Chinaman flogged while another was tortured. However, when they seized a Christian Sangley, Antonio de Morga, head of the Royal Audiencia, stopped them. The Governor-General then issued a decree forbidding the hurling of insults against the Mandarins and mandating punishment to those who molest them and at the same time prohibiting the Mandarins from arbitrarily administering justice in the fledging colony. The formation of the soldiers and retainers of the three Mandarins is faithful to the description found in the 17th century manuscript that depicts their arrival. The Mandarin retainers carry banners showing the creatures illustrated in the Boxer Codex, a 16th century manuscript. In the background, imprinted on the walls, are scenes of the impending massacre of the Chinese that occurred after the departure of the three Mandarins.

The Three Mandarins

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 8 feet

Moros y cristianos

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

Padre Juan de Salazar, who witnessed the game, must have had a rich imagination and perhaps he envisioned the tremendous possibility of writing a comedia as a concrete device for religious instructions. Thus inspired, his prolific pen produced “Gran comedia de la toma del pueblo de corralat y conquista del cerro”. (The Greta Play of the Taking of the Town of Kudarat and the Conquest of the Hill.) This traditional warlike play developed several variations. In the Island of Cuyo, that lonely citadel of the Spanish faith where church and fortress merge into one, the Moro and Christian war is re-enacted (pananapatan) on the streets for the public to see and enjoy. The palipasan and baligtaran are the main parts of the dance, in the end, there is reconciliation between the two groups and the Christians offer peace and baptism to the Moros whom they had defeated.

This HOCUS painting shows the combatants of the religious war engaged in mortal combat beyond the grave, the tragic consequence of their internecine religious conflicts. Onlookers watch the tragic spectacle. A Diogenes-like figure carrying fighting cock and a lamp searches for the one true Faith. Two old lovers about to be separated by death as symbolized by the white rose on their feet, bid each other farewell. Two chess players trade strategies over an empty chessboard with the pieces scattered all over the floor. The symbolism is obvious, in religious conflicts, the only way to win is not to play.

Moros y cristianos

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

Cofradia de San Jose

Oil on canvas, 3 feet x 4 feet

Apolinario de la Cruz was born in 1815 in Lucban, Tayabas, now Quezon Province. His parents were Pablo de la Cruz and Juana Andre, both peasants. Apolinario founded the Cofradia de San Jose (The Brotherhood of St. Joseph) on December 12, 1832; its complete name was Hermandad de la Archi-Cofradia del Glorioso Señor San Jose y de la Virgen del Rosario (Brotherhood of the Great Sodality of the Glorious Lord Saint Joseph and of the Virgin of the Rosary). The Cofradia was composed of farmers and peasants.

To break up the congregation, on March 22, 1841, Tayabas Governor Joaquin Ortega arrived with his troops, but because of the numerical superiority of the Cofradia members, Ortega was killed. The Captain-General of the islands then mobilized land and sea forces and sent to Tayabas under the command of Lt. Col. Joaquin Huet. On November 1, 1841, the Spaniards, together with their native auxiliaries staged an attack.

Six to seven hundred men and three cannons of the colonial army were pitted against three to four hundred, not counting the aged, women, and children. Pule was defeated and three hundred women were taken prisoners. Pule was captured on November 2 and was executed in Tayabas on November 4, 1841. His body was quartered and sent to different parts of the province for public display. He was only 27 years old.

In this HOCUS painting, the members of the Cofradia are seen praying, surrounded by novenas and a myriad of anting-antings. Behind Them is a native angel who has obviously displaced the European-looking one in the hearts of the indios. No wonder the European angel is seen whispering conspiratorially to a Franciscan friar.

Cofradia de San Jose

Oil on canvas, 3 feet x 4 feet

Staking Territory

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

On March 13, 1620, two Dominicans, Fray Juan de San Jacinto and Fray Francisco de Ugaba petitioned Garcia de Aldana, Alcalde Mayor of the Province of Pangasinan, that an order be given to a notary to enable the Orden de Predicadores (i.e. the Order of Preachers or the Dominican Order) to spread the word of God among the Igorots and thereby confirm their exclusive rights to the province of Benguet. Aldana then ordered that the petition of the two priests be carried out. Tomas Perez, being the Escribano de Minas y Registros, testified that Father San Jacinto, Vicar of the province of Manauag, did say Mass by a river inside the province of the Igorots. A testimonia also stated that on March 15 through March 17, 1620, the two Dominicans said Mass and conferred sacraments unhindered, in the province of the Igorots. The sacrifice of the Holy Mass was made to signify the formal taking of possession of the ecclesiastical rights of the province by the Dominicans.

Thereafter, all other religious orders were barred from asserting jurisdiction over the province of the Igorot skylanders. Thus, by the saying of a Mass, the re-enactment of the Last Supper of Christ, a territorial claim was made and sealed. Maybe the mass at Limasawa or Butuan were celebrated with the same intent, to stake territory for the Spanish crown.

In this HOCUS painting a Dominican friar is saying a Mass near a river in front of the sacred mountain of the skylanders. Little did the Igorots know that a foreign power has staked its claim to their ancient lands through the holding of an ancient ritual originating from a land two oceans away.

Staking Territory

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

Artisans of the Faith, Washers of Souls

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

The friars were tasked to capture our souls so the soldiers could occupy our lands and demand tribute. This is evident in a letter written in the 16th century by a Captain Juan Pacheco Maldonado to King Philip II of Spain. The following are passages from the said letter: “Second, your Majesty will be pleased to send also, with the said religious, a prelate, the reverend father Fray Diego de Herrera, of the Order of St. Augustine. The father is a man of learning and of good life, who has labored much for the conversion of the Indians of those islands. With him send us many of the secular clergy as your Majesty pleases…”

This allegorical HOCUS painting shows friars as artisans sculpting

statues of numerous saints, the Blessed Virgin and Jesus Christ. They also built churches, reminiscent of those in their hometowns in Spain, using local materials like coral stones, tropical hardwoods and adobe. They forcibly recruited natives, to quarry and do construction work, carve imposing retablos and paint murals on walls and ceilings. In the lower portion of the painting, beneath the steps, nuns and priests of various religious Orders are seen washing the tainted souls of indios who, according to the religious doctrine introduced by the friars, should be liberated from sin before they are released to the afterlife.

Artisans of the Faith, Washers of Souls

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet