Paintings

HOCUS II

The Hofileña-Custodio paintings exhibited at the National Art Gallery of the National Museum of the Philippines on September 15, 2019 to March 15, 2020

The Dreamweavers

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 8 feet

In Lake Sebu, Cotobato, settles the T’Boli. They make T’nalak cloth. T’nalak is made from the fibers of the abaca and the designs are conveyed to them in their dreams by their gods. One of their gods is Fu Dalu. She is described in T’boli lore as a spirit who protects the integrity of the abaca so the fibers will not break during the weaving process.

In this HOCUS painting, clockwise from upper right, a T’boli woman weaves the M’Baga Klagan that shows the pattern of Loos Klagan, a T’boli spirit that inflicts diseases. The T’nalak cloth is used to appease Loos Klagan so that, according to the Tiboli tradition, they may be protected from afflictions that may plague them. Below, another woman weaves the Klagan T’nalak cloth on a loom with the pattern of Fu-el, the T’boli goddess of waters. Below, on the left, the weaver executes a design, of the ogow tenbe beniteng, which is the T’boli mermaid, whose long hair flows with the seas, rivers and lakes. Above the weaver of the beniteng, another T’boli woman intertwines abaca threads to make the M’Baga F’low which protects one from the F’low or a bad spirit; offending the F’low may lead to illness, if not death.

At the very center stands Fu Dalu, the serene Goddess of the Weave who reigns over the enchanting lake. Unknown to her, a Christian Cross is slowly emerging from the lake. The cross is draped with a T’nalak with the Buling Longit design that symbolizes an imagined heaven gloriously adorned with the patters, colors and images of all the T’boli dream weaves since time immemorial.

The Cross of the Spanish missionaries looms over Lake Sebu replacing Buling Longit. They have assimilated the symbolic vocabulary and the woven syntax of the mystical dream patterns conveyed by the T’nalak. Will the T’boli be Christianized and made subjects of the King of Spain? History says that some T’bolis did become Christians but some stuck to their old ways and the faith of their ancestors.

The Dreamweavers

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 8 feet

Permanent Exhibit, National Museum of Anthropology, Republic of the Philippines

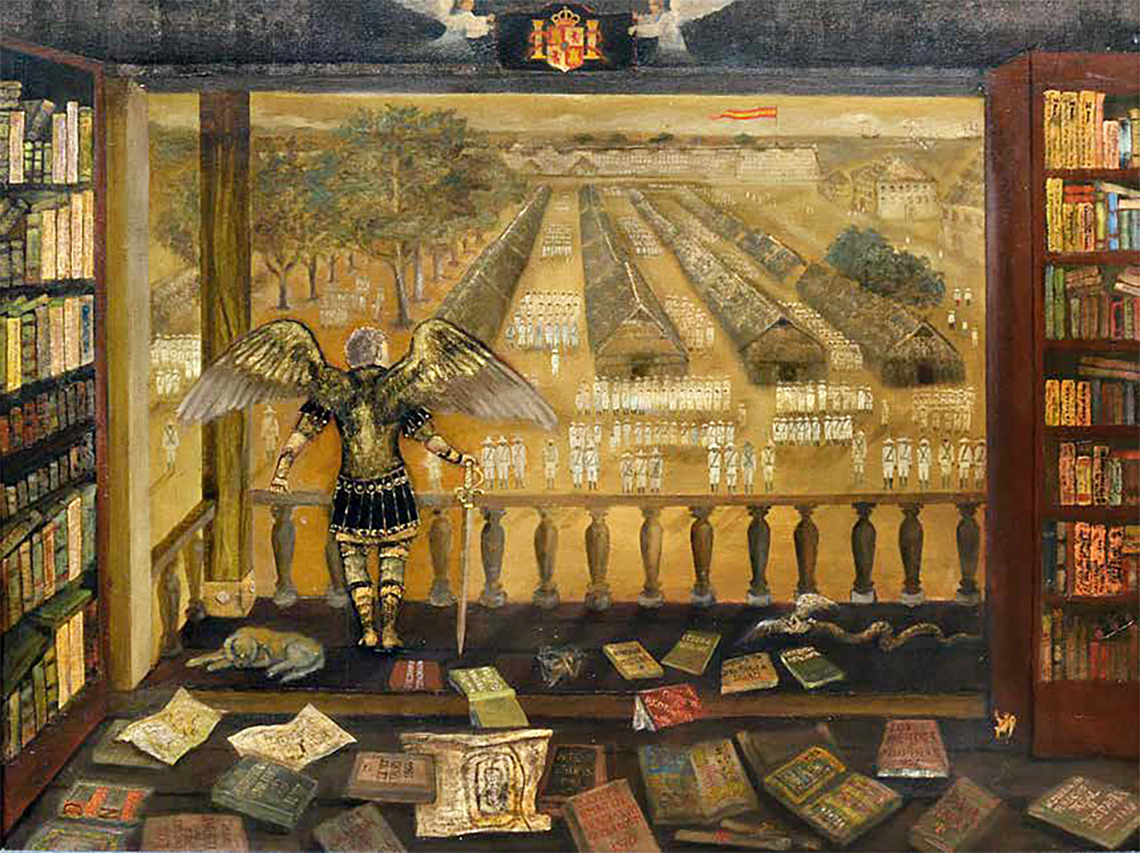

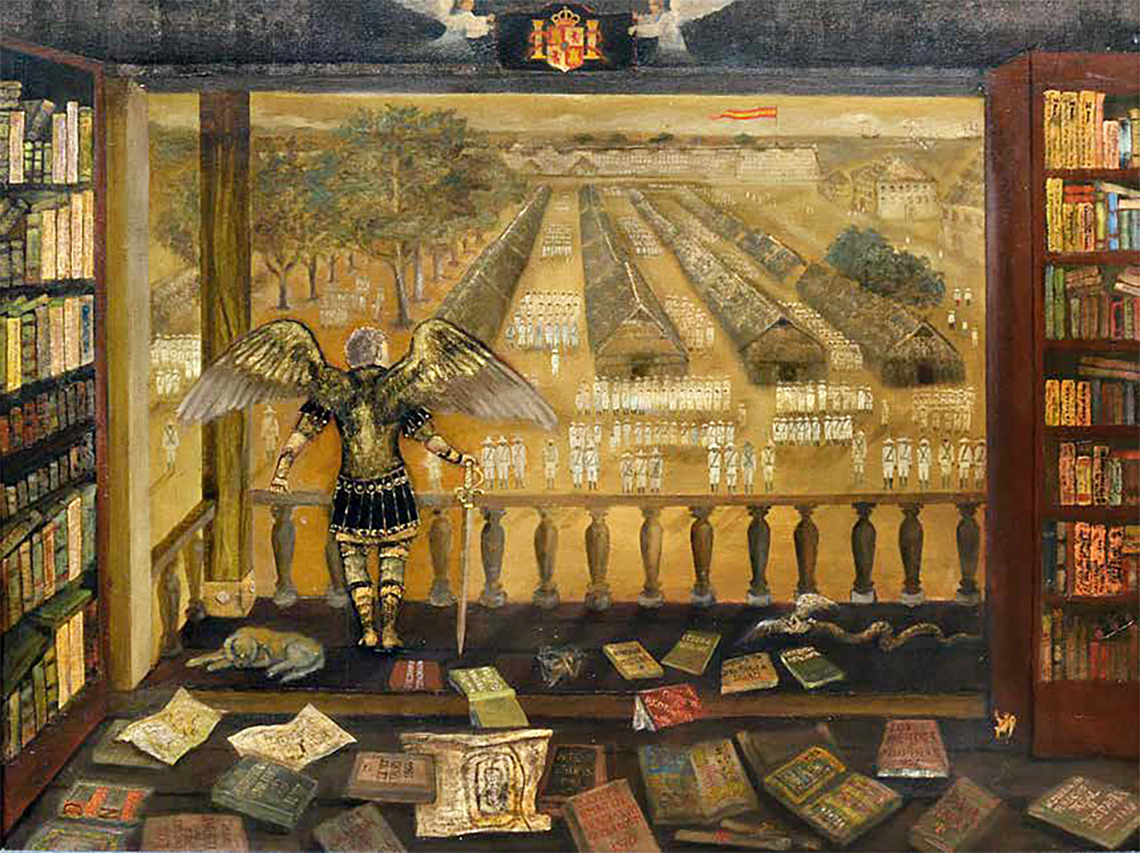

The Reading List

Oil on canvas, 3 feet x 4 feet

After the destruction of the Aztec empire in Mexico, heavenly hosts of archangels came to the Capitanía General de Filipinas, Spain’s colony across the Pacific. This angel-conqueror surveys the armies of the Spanish Empire stationed in Zamboanga. The accoutrements of this celestial subjugator— black armor embellished with the gold of the Aztecs—project the power of the Empire. Behold the symbols—a drowsy Burgos Pointer, a breed native only to Spain; a Mexican viper devouring a Mindanao scops owl; a litter of military maps and books, among them El Indio Agraviado, Vocabulario Iloco-Español, Leyes de Toro, were some of the intellectual tools of conquest. Although allegorical, this HOCUS scene is historically accurate; there was indeed an encampamiento in Zamboanga where Spanish troops and auxiliaries were stationed on their way to engage in battle the Moros of Jolo and Patikul.

The Reading List

Oil on canvas, 3 feet x 4 feet

The Virgin has Nothing to Sell

Oil on wood, 7 feet x 3 feet

During the Spanish colonial period, the most popular shrine in Antipolo was that of Our Lady of Peace and Good Voyage.

Walter Robb, a former pre-war newspaperman in the Philippines, quoted an Englishman who described a shameful occupation of those who were too lazy to work. They carried around a display case containing a small image of Our Lady of Peace and Good Voyage enclosed in glass. They presented this to devotees who were on their way to Our Lady’s shrine in Antipolo; the pilgrims were invited to hold the case and kiss the Virgin, after which they were made to pay a small fee.

Alas, the Virgin has nothing to sell! Our Lady of Peace and Good Voyage has never charged for the miracles demanded by the pilgrims whose souls need to be blessed.

This HOCUS painting shows how the unscrupulous make money on the devotion to the Virgin of Antipolo. To the left of the Virgin and to her right, there are makeshift stores selling numerous religious objects to the droves of pilgrims who come to ask for her protection.

The Virgin has Nothing to Sell

Oil on wood, 7 feet x 3 feet

A las ocho de la mañana, 30 Deciembre 1896

Oil on wood, 7 feet x 4 feet

This HOCUS painting is a tribute to Doña Teodora Alonzo, the exemplary mother. “Education begins on a mother’s lap…” Rizal wrote to the 20 young women of Malolos who wanted to open a school. He had his mother in mind. Here Doña Teodora is dressed in mourning, two hours after the death of her son, showing us her son’s last poem where he bade his family and friends farewell: Adios, padres y hermanos, trozos del alma mia, amigos de la infancia, en el perdido hogar. Her handkerchief is stained with his blood. She offers it to you. Will you take it and follow Rizal’s example of love of country or would you just turn and walk away?

A las ocho de la mañana, 30 Deciembre 1896

Oil on wood, 7 feet x 4 feet

Jugadores de cartas muy confiados

Oil on canvas, 3 feet x 4 feet

This HOCUS painting shows four card players in obvious mirth playing the Cartas Philippinensis. The Cartas Philippinensis is a set of Tarot cards which I designed and which is the only playable tarot cards with Philippine themes. According to Maria Cristina Barrón Soto (Ph.d) of the Universidad Iberoamericana, Ciudad de Mexico: “The cards are glimpses of the syncretism of the Catholic faith which when fused with the forces of nature, enrich and balance what is sacred to the Filipino people and bring to the fore a Spanish identity rooted in Christian tradition.

Although the tarot cards are used for divining one’s future, the cardplayers have somehow devised a way to satisfy their gambling instincts by using the Philippinensis cards. The card players by their gaiety disclose that they are unaware of the history that the Philippinensis cards reveal, like the blindfolded friars in the painting who are equally unaware that the blind doctrines that they have taught will traverse centuries and fester in the minds of the people of these islands.

Jugadores de cartas muy confiados

Oil on canvas, 3 feet x 4 feet

Triduana

Oil on canvas, 5 feet x 4 feet

This HOCUS painting shows a Spanish woman from Andalucia, with the traditional peineta and mantilla, flipping the Cartas Philippinensis. She represents the Spanish empire which controlled the daily lives of the people it governed. Most of the conquistadors came from Andalucia. Members of four friar orders are seen flying distinctively South-East Asian kites carrying the symbols of the Four Evangelists: Matthew is symbolized by a man, Mark by a winged lion, Luke by a winged ox and John, an eagle. The friars are mounted on pulpits found in churches where they held sway.

Below left, an Augustinian is perched on the pulpit of the San Agustin Church. Above him is a Dominican flying a kite from the pulpit of the former Sto. Domingo Church in Intramuros which was destroyed during WWII. To the right, a friar of the Franciscan Order, stands on the pulpit of Maragondon Church and below him a Jesuit flying a kite from the pulpit of Baclayon Church which was built by Jesuits and later occupied by Recoletos after their expulsion. The Andalucia woman, the friars, and the symbols of the gospel preachers, shows in allegory how our souls were pacified through a symbiotic relationship of Church and State which consequently led to the loss of our lands and identity.

Triduana

Oil on canvas, 5 feet x 4 feet

The Sailing Ships

Oil on wood, 4 feet x 3 feet

The friars believed that the Philippines is their springboard to China and China must be introduced to the Christian Faith.

In this HOCUS painting, the 5 religious orders—Augustinians, Jesuits, Recollects, Franciscans and Dominicans, together with soldiers of the Spanish crown, are seen crossing the Pacific.

The little rocks on the left is actually Islas Filipinas since this was how Filipinas was represented in a 16th century map of Sebastian Munster. The creatures on the lower part of the panel are the strange creatures that the religious and the conquistadors expected to see in their perilous voyage. The cross occupies the center of the compass on the lower right hand corner of the painting and on the upper left of the painting is an outline of the coastline of China.

The Sailing Ships

Oil on wood, 4 feet x 3 feet

Secrets of the Laguna Copperplate

Oil on canvas, 3 feet x 4 feet

The Laguna Copperplate is the oldest written document of the

Philippines; it was not easy to decipher its secrets. The journey of its discovery began in ancient burial grounds, a place now called Dulongbayan, in Lumban, Laguna, which became a major source of pre-Hispanic artifacts coveted by Filipino collectors in the 1960’s.

In this HOCUS painting, the copperplate is shrouded with vestiges of our pre-Hispanic past: A Javanese Kinnari lamp is seen on the right; there are two golden death masks, circa 10th-13th century A.D. excavated in Butuan, Agusan del Norte; on the left sits a golden figure of the deity unearthed in the area ruled by an ancient kingdom in Surigao. Another golden effigy of the half-man half-bird kinnari, also from Surigao, is seen at the right. Bejeweled pre-Hispanic natives straight from the Boxer Codex amble through the cryptic script bequeathed by our ancestors.

Finally, the copperplate shows the story, in old books retold, of a native who clambered up a coconut tree and shouted to the encamped Spaniards: “What have we done to your ancestors to justify your cruelties?”

Secrets of the Laguna Copperplate

Oil on canvas, 3 feet x 4 feet

Permanent Exhibit, National Museum of Anthropology, Republic of the Philippines

Escuelas y rosarios

Oil on canvas, 3 feet x 4 feet

The learned Jesuit historian Rene Javellana speaks of the narration of Pedro Murillo Velarde of the daily routine of a typical town. The village boys and girls start the day with masses, thereafter, they proceed to school singing prayers. Known as escuela y rosarios, “their comings and goings were marked with the singing of prayers. Hence, the stillness of the country air was rent by the singing of children, as the songs indoctrinated the rest of the village with Christian doctrine through prayers.”

In this HOCUS painting, children are seen going up the first staircase of the Escuela Catolica chanting religious songs. As if transported into the future, the very same children go down the second staircase as adult musicians and singers, their latent skills honed by a conspiracy of age and time. This is an allegory that explains why Filipinos are known the world over as talented musicians and singers. Indeed, if other nations have dominated the world with their armies, we have conquered it with our vocal chords and our ability to play musical instruments. Take note of the two children looking at the Escuela while leaning on an elderly couple, the past and the future are back to back. The past is indeed a prologue.

Escuelas y rosarios

Oil on canvas, 3 feet x 4 feet

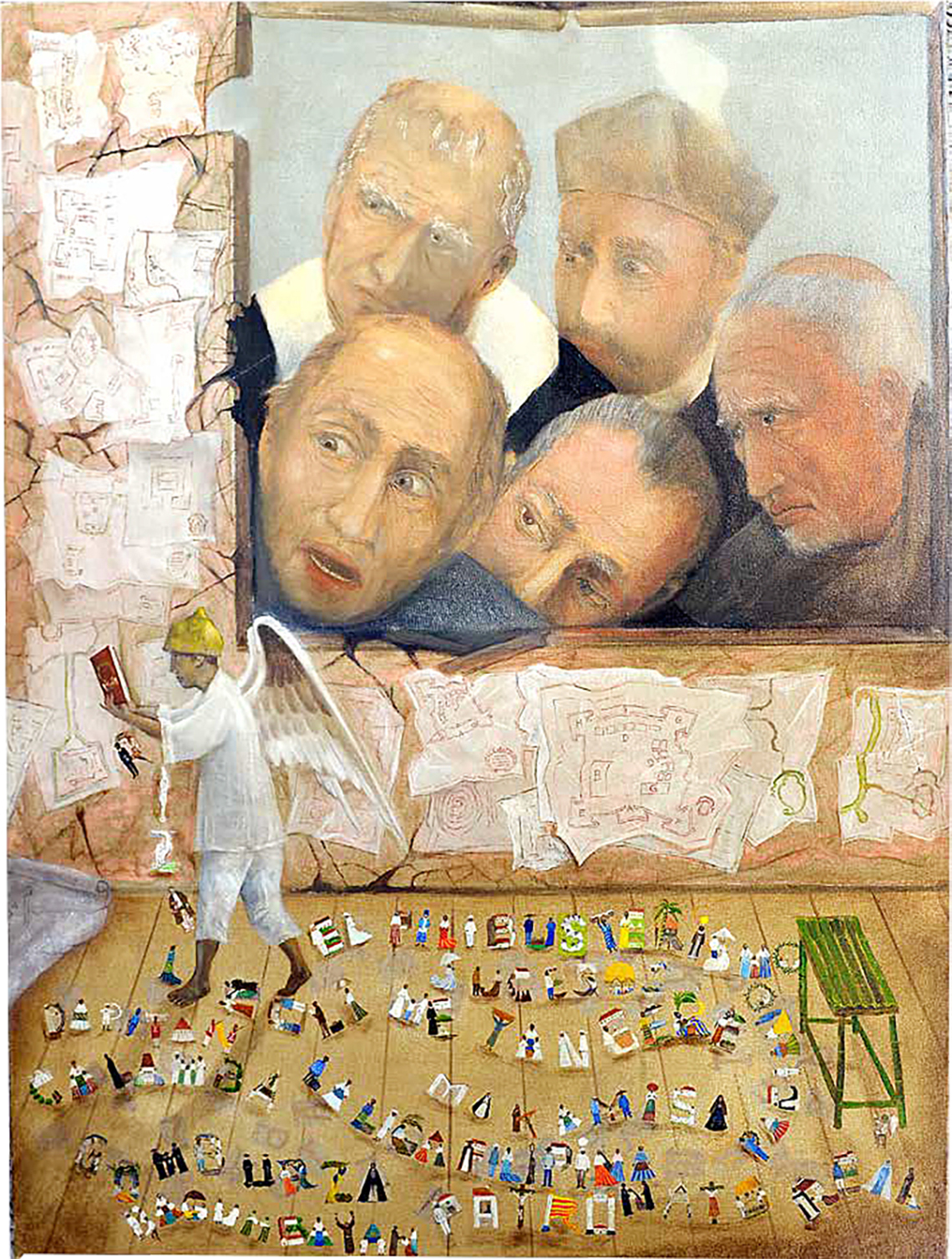

The Reading List 2

Oil on canvas, 3 feet x 4 feet

On December 30, 1896, at 7:03 in the morning, the eight-man squad of the 70th Infantry Regiment, the “Magallanes” shot Jose Rizal. How tragic that Filipinos were made to kill a compatriot. This HOCUS painting

envisions the scene after Jose Rizal was executed by firing squad.

It was Rizal’s death that galvanized the Filipinos to fight a deadly war of independence against 333 years of Spanish rule. Witnessing the execution from her window, a Filipina angel weeps inconsolably, surrounding her are the books that caused Rizal’s death: The Noli Me Tangere and the El Filibusterismo both written by Rizal. Books authored by the friars responsible for his death litter the floor and are stacked on the bookshelves—Obras de Santa Teresa de Jesus, Arte de la Lengua Tagala, Antiguos Alfabetos Filipinos, EL Indio, Platicas y conferencias, Libro de Almas, Vocabulario de la Lengua Pampanga, etc.

The Reading List 2

Oil on canvas, 3 feet x 4 feet

Angels Visit the National Museum, at Midnight

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 8 feet

La Pesadilla is a kind of palimpsest because it has been painted over countless times. I spent many tormented nights visualizing the multiple details of its symbols and hidden messages. Harder still was explaining to Guy Custodio the visions in my mind. In fact, if the painting chaffs, its underlay would reveal the changes Custodio had to make until he finally understood what I was seeing in my mind. After the “La Pesadilla” triptych was donated to the National Museum of Fine Arts for permanent exhibition, I felt personal loss. It is for this reason that I asked Custodio to duplicate the painting in a smaller scale, with angels visiting it at the National Museum of Fine Arts, at midnight.

As the angels contemplated “La Pesadilla”, they were shocked to see what has been happening. The lead angel is angry, his fury obvious even if his back is turned. The sword of a second angel has turned into a flaming blade which happens whenever angels are overcome with rage. This is a vision that I had in a dream and which I asked Custodio to paint on canvas. Now I have my “La Pesadilla” back.

Angels Visit the National Museum, at Midnight

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 8 feet

Hang the Heretic

Oil on wood, 6 feet x 3 feet

The Anghel de Cuyacuy is seen hanging from a tree, the noose around his neck killed him by asphyxiation. Who meted this terrible punishment? What capital sin did the Anghel de Cuyacuy commit to deserve such a horrible death? He is surrounded by priests of the Holy Orders, one carries a bell, the second a book and the third a candle, which can only mean that, in these islands, even angels can be excommunicated. Another anghel de cuyacuy emerges from the rubble of the Oton church. The friars, wrapped in dogma, had accused the anghel of heresy, both religious and historical. That was why they hung him. However, armed only with his books and his seemingly blasphemous interpretations of religion and history, the Anghel de Cuyacuy is beyond the pale of death since he is an angel—a minor fact which the friars seem to have forgotten.

Hang the Heretic

Oil on wood, 6 feet x 3 feet

Suitor & Soothsayer

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

This is a HOCUS painting within a HOCUS painting.

The painting on the wall is surrealistic. A squad of Guardia Civil is forcibly pulling down a moon with a human face. Coincidentally, Bonifacio’s flag had an anthropomorphic sun which became a symbol of the

Philippine Revolution, symbolizing the dominant role that the Giardia Civil played against those who fought for our freedom. In single file, Filipino peasants cross a green field, one carries a fish followed by two others transporting a recumbent friar clutching a rosary in his left hand. The last man with a native raincoat is holding an enormous crab.

In the background, a ruined Pinaglabanan bridge in the then pueblo of San Juan spans a shallow pond for carabaos. Yet, two bancas are seen navigating an invisible river; the first carries the image of Nuestra Señora de la Soledad de Porta Vaga, of Cavite, and the other, the Nuestra Señora de Peñafrancia of Bicol. Both are honoured with fluvial processions. They mimic the religion introduced by Spain to the indios, part flight of fancy, part based on the indio’s everyday undertakings

Suitor & Soothsayer

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

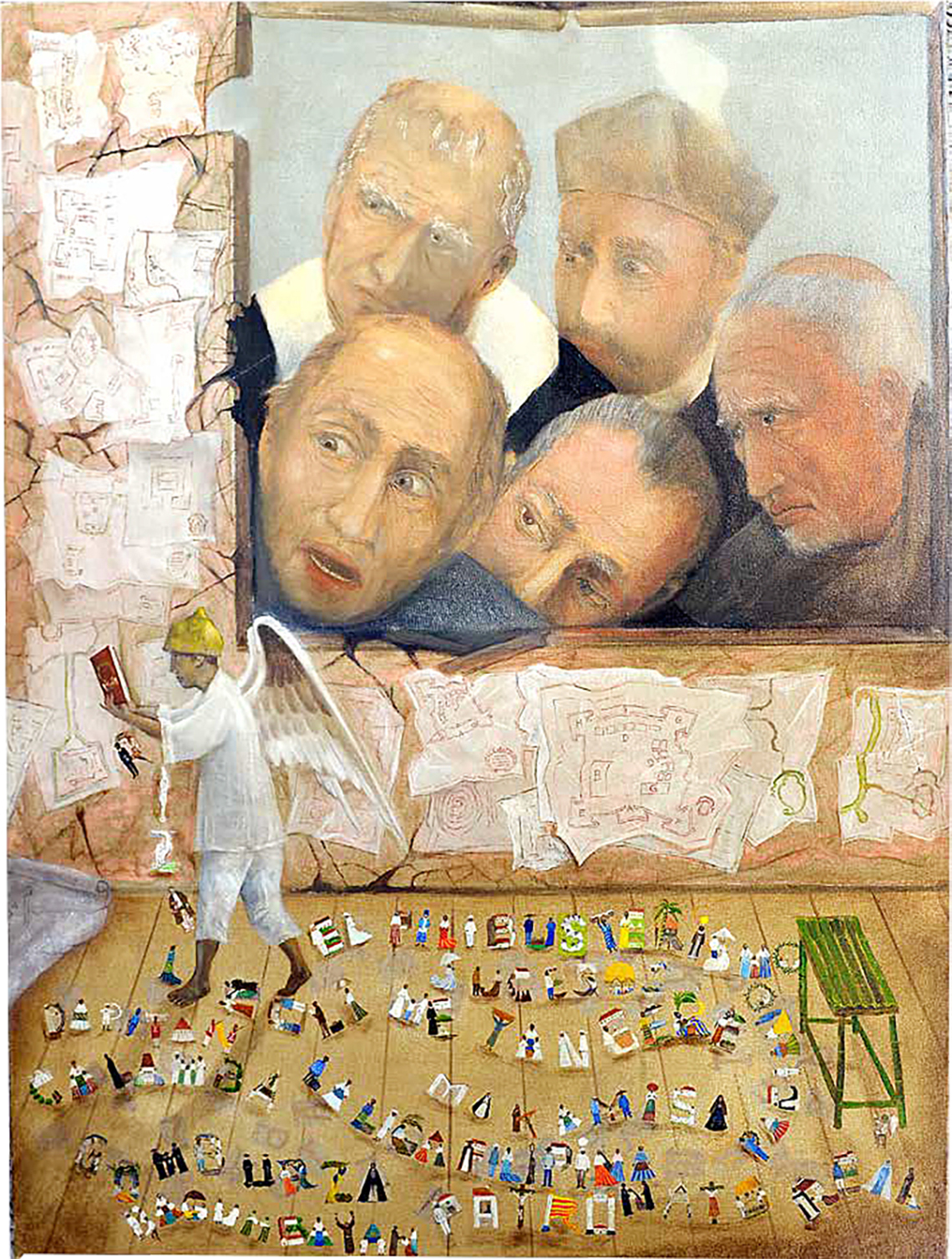

Anghel de Cuyacuy

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

This painting shows the Anghel de Cuyacuy. He is a Filipino angel destined to battle ignorance and superstition and not Satan’s murderous horde.

Behind him are the members of the religious orders looking intently at the cuyacuy angel. A Dominican whose face exhibits anger, a Jesuit in shock, a Franciscan whose face shows amazement, an Augustinian likewise registers his astonishment and a Recollect, his sorrow.

The walls around the anghel de cuyacuy are crumbling. The walls are decorated with the plans for the various forts built by the Spaniards in the Philippines.

Anghel de Cuyacuy

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

The Descending Christ

Oil on wood, 4 feet x 3 feet

So that the confusing concept of the Trinity may be explained, artists during the Spanish colonial period came up with three identical images of Christ. Jesus Christ, the son, is shown with the image of the lamb of God on his chest. Another Christ representing the Holy Spirit is shown with a white dove and Christ the father almighty is shown with the all-seeing eye also embedded on His chest.

In this HOCUS painting, the three persons of Christ are shown descending a stairway with the deeply religious Andalucia province at the background. Each Christ figure instead of the usual symbol of the dove, the all-seeing eye and the lamb is shown with the number three.

The Descending Christ

Oil on wood, 4 feet x 3 feet

A Convent on Isla del Fuego

Oil on canvas, 2 feet x 3 feet

In this allegorical HOCUS painting, the natives do not seem at all impressed by the dramatic religious structures that were transforming the landscape while their lives remained the same. They were far from prosperous and on a carabao-drawn cart, following the friars in their drunken and merry jaunt.

The allegory notwithstanding, the Augustinian Recollects did leave a precious legacy, the Lazi Convent which was declared a National Historical Landmark in 1978 and National Cultural Treasure in 2006.

A Convent on Isla del Fuego

Oil on canvas, 2 feet x 3 feet

El Canto Boholano

Oil on wood, 6 feet x 5 feet

A kyriale is a liturgical song book of Gregorian chant for the Ordinary of the Mass sang by a congregation. I have been fortunate enough to see

those enormous songbooks made from the hide of luckless animals in the church museums of Bohol, before a destructive earthquake hit the island in 2013.

This HOCUS painting shows the title page of the Antifonario de esta de Baclayon.

The music paleography had been changed: Instead of the usual neumatic notation of Gregorian chant, the symbols of Bohol were superimposed on the square musical notes, but one can still sit in front of a pipe organ and play this unusual kyriale to hear the ancient music.

El Canto Boholano

(The Song of Bohol)

Oil on wood, 6 feet x 5 feet

Using Occam’s Razor

Oil on canvas, 5 feet x 3 feet

This HOCUS painting is an allegory of how the Katipunan was discovered. On the foreground Teodoro Patiño confesses to Padre Gil in a proper confessional box. To the friar’s right, a soldier from the infanteria and a member of the officer corps of the Guardia Civil Veterana listens sub rosa to the confession of Patiño being heard by Padre Gil. (According to Fray Gil’s testimony, he first went to the infanteria then to the Guardia Civil). The organizational chart of the Katipunan is traced on the sand but a sea of blood is about to wash it away. Above is the church of Tondo where Fray Mariano Gil was cura parroco and where he received the confession of Patiño. The church is about to be hit by a fireball in the night, a cosmic portent of the coming revolution sparked by Patiño’s confession and Fray Gil’s betrayal of the Seal of Confession.

Using Occam’s Razor

Oil on canvas, 5 feet x 3 feet

‘Time is’ ….. ‘Time was’ … ‘Time’s past’

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

The lady time-keeper is an india and directly above her head a clock indicates when Jose Rizal was born, when he published the Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo and the year he was executed at

Bagumbayan.

The lady is sewing what appears to be the first Philippine flag, exactly like the one Marcela M. Agoncillo described as our first flag with four stars and a human face, our flag, the symbol of the aspirations of the Filipino people that was gloriously unfurled during our country’s declaration of independence. The timepieces mark the memorable years.

‘Time is’ ….. ‘Time was’ … ‘Time’s past’

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

The Burning Book

Oil on canvas, 5 feet x 4 feet

The Bible—a written record of God’s messages to Man—is the work of more than 35 writers and poets. Its compilation and writing took more or less a millennium. As holy as the Koran is to Islam, the Bible is taken as divine writ. Early Christian texts were written mostly on papyrus but the use of animal parchment became popular in the fourth century. The Old Testament was written in Hebrew while the Gospels of the New Testament were written in Greek. Saint Jerome, patron saint of bibliophiles, translated the Bible to Latin vulgate, thus making the holy book more accessible and readable to the educated classes for Latin was then the lingua franca of Europe. In 1455, Gutenberg came out with the first printed Bible which made it more popular.

In this HOCUS painting, friars of the religious orders, during the Spanish colonial period, identified by the seals on their gold rings, are seen chasing the Roman, Hebrew and Greek letters that leaped out of the pages of a Bible in flames. Thirteen dragonflies symbolizing the crucified Christ and His twelve apostles are also seen in drastic flight. The bible burns because of the religious orders have blasphemed the Faith.

The Burning Book

Oil on canvas, 5 feet x 4 feet

Miracles of the Faith

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

A priest, ensconced on a silla de frayle, is actually a composite image of the 5 religious orders. He is barefooted, like a member of the Order of the Recoletos Agustinos Descalzos (the barefooted Augustinian Recollects).

He dons a Jesuit hat. He wears the long sleeve cloth of the Augustinians and his legs shows the vestments of the Franciscan Order.

He is surrounded by paintings showing the miracles that helped to strengthen their grip on the soul of the indio. From upper left, counter clockwise, the painting shows the battle between the Spaniards and the Dutch. The former was aided by the Virgin Mary. Thus, we have the yearly procession of La Naval de Manila to commemorate the killing of those Dutch sailors. Below is shown the church of Boljoon in Cebu, Legend has it that a giant armed with a canon protected the inhabitants of the town from Moro pirates. The town Boljoon was a pre-Hispanic settlement. The pueblo was one of the most plundered by the Moros since it is located on the Southern portion of Cebu. Boljoon was christianized by the

Augustinian friars. In 1599, it was listed as a parish like Carcar and Argao. In 1624, Boljoon became the encomienda of Pedro de Madrid. In 1782, it was reduced to ashes and the only things saved from the onslaught of the Moro pirates were the town virgin and sacred clothing of the friars.

Miracles of the Faith

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

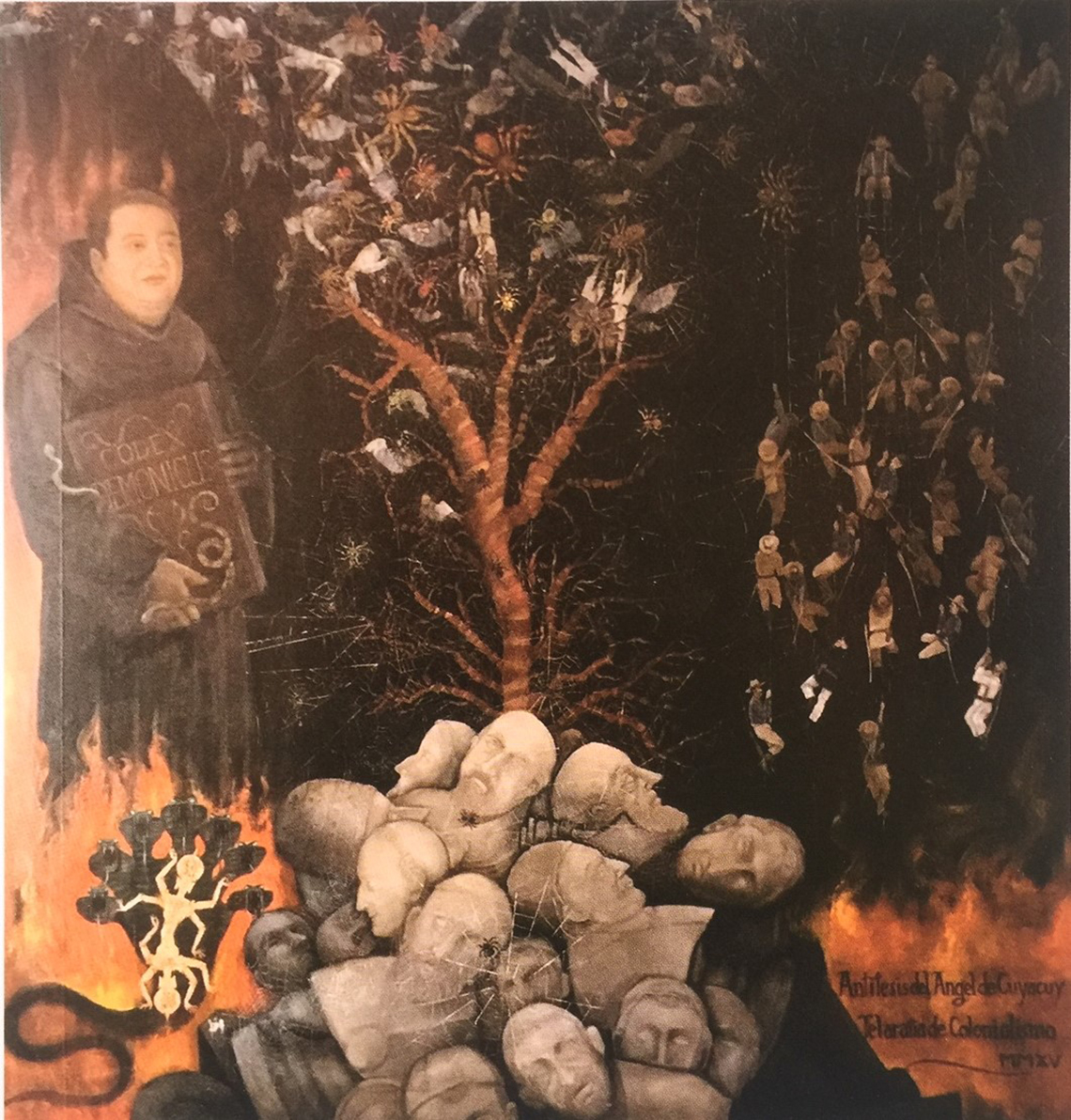

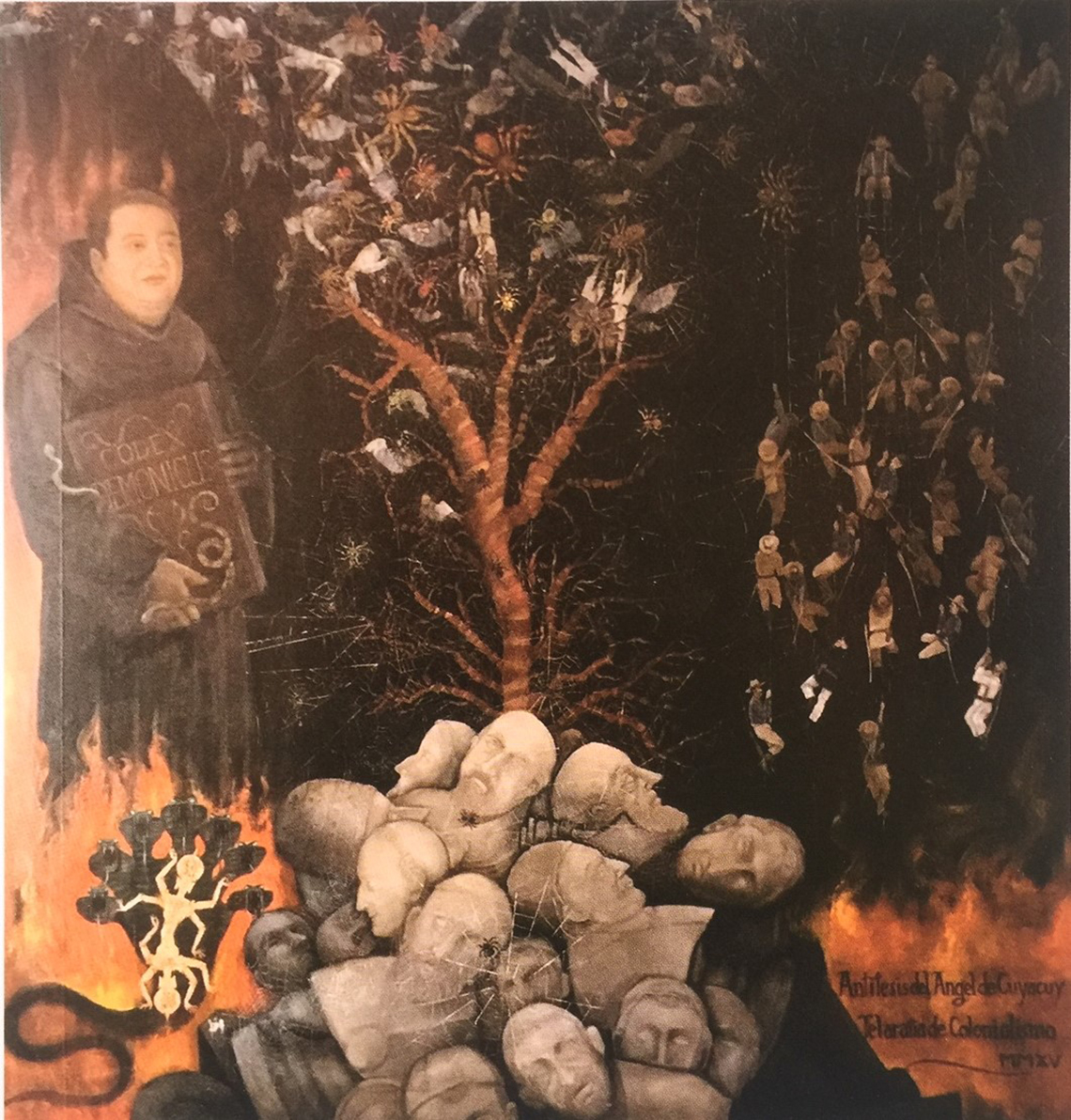

Antitesis del Angel de Cuyacuy/Telaraña del Colonialismo

Oil on canvas, 7 feet x 6.5 feet

The Antithesis of the Hocus angel cradles the Codex Demonicus.

Below him is the seven headed Naga with a stylized version of the Agusan Goddess which was found in 1917 on the banks of the Agusan River after a turbulent storm. The image was taken by the Americans to the United States and is now on display at the Field Museum of Chicago. Together, they symbolize the faith that has come to these shores before the coming of the Europeans.

Below the Antithesis is a pit containing the busts of the popes who reigned during the time of Spanish sovereignty in the islands. From 6 o’clock clockwise: (1) Gregorio XVI. (2) Paulo IV. (3) Inocencio VII. (4) Alejandro VI. (5) Jan Pio V. (6) Clemente IX. (7) Inocencio X. (8) Pio II. (9) Benedicto XIII. (10) Sixto V. (11) Benedicto XIV. (12) Marcelo II. Above the busts is the Dendronephthya, a coral that inhabits the waters of the Western Pacific—the path taken by the conquistadors coming from Mexico.

Enmeshed in the cobweb of colonialism in various stages of death and near death are the Spaniards and their native auxiliaries—caught in the silken quagmire of their own doing. Soldiers from the North American continent are seen climbing towards the woven threads that have entrapped their predecessors, not realizing that they too will be ensnared in the deadly game of empire building.

Antitesis del Angel de Cuyacuy/Telaraña del Colonialismo

Oil on canvas, 7 feet x 6.5 feet

Permanent Exhibit, National Museum of Anthropology, Republic of the Philippines