Paintings

HOCUS I

The Hofileña-Custodio paintings exhibited at the National Art Gallery of the National Museum of the Philippines on April 18, 2017 to October 29, 2017.

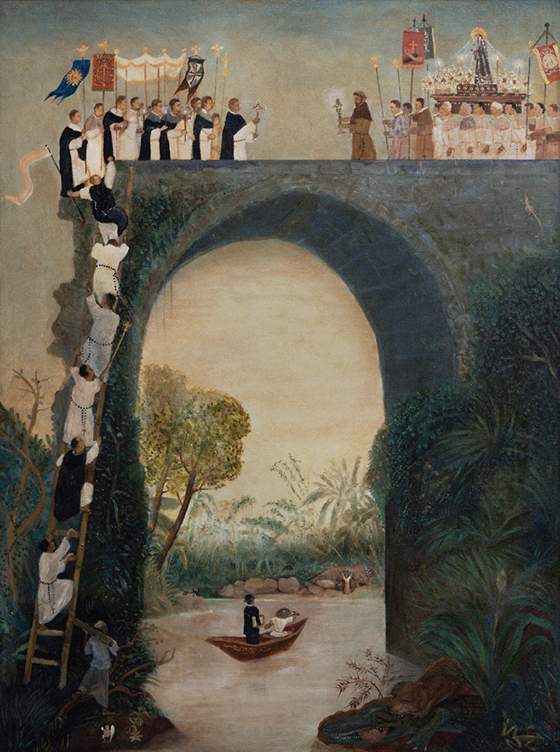

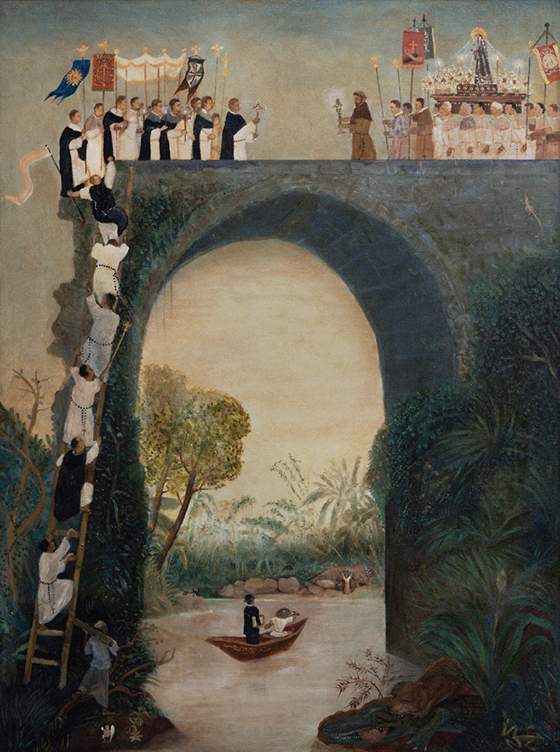

Puente de capricho (The Bridge of Caprice)

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

In the remote but enchanting town of Majayjay, Laguna, there is an unfinished 19th century stone bridge called Tulay na Pigi so called because the Franciscan friar who ordered its construction would cane the indios on their pigi (buttocks) for not working fast enough. The bridge was never finished for either lack of funds or maybe because of the turf war it provoked between the Dominican and Franciscan Orders. The former may have resented the presence of the latter in the province of La Laguna. The bridge, called Puente de Capricho (the Bridge of Caprice) was mentioned in Rizal’s El Filibusterismo.

This HOCUS painting dramatizes that internecine conflict: on the left, the Dominicans feverishly clamber up the bridge to engage the Franciscans head on. Both orders are seen brandishing their religious symbols and images of their Orders, as if these were weapons of war. Meanwhile, on the river below, Jose Rizal, riddled with bullets, his novels tucked under his arm, escapes with a boatman on a bangka decorated with the frieze that he had sketched on the Noli’s cover. The scene is replete with details associated with Laguna’s heroic son: a draco rizali, the winged lizard of Dapitan, creeps up the bridge; a disheveled Sybilla Cumana frantically waves a warning at the two fugitives;

a deceitful monkey argues with a guileful turtle. At bottom right, a dog desperately attacks a crocodile to avenge the death of her pup, Rizal’s Ang Paghihiganti ng Isang Ina (Revenge of a Mother). An india water carrier is seen at far left; she is torn between following the Dominicans up the bridge, or Rizal in his fight for freedom.

Puente de capricho (The Bridge of Caprice)

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

La Virgen en un rincón de Cavite (The Virgin in a Corner of Cavite)

La Virgen en un rincón de Cavite

(The Virgin in a Corner of Cavite)

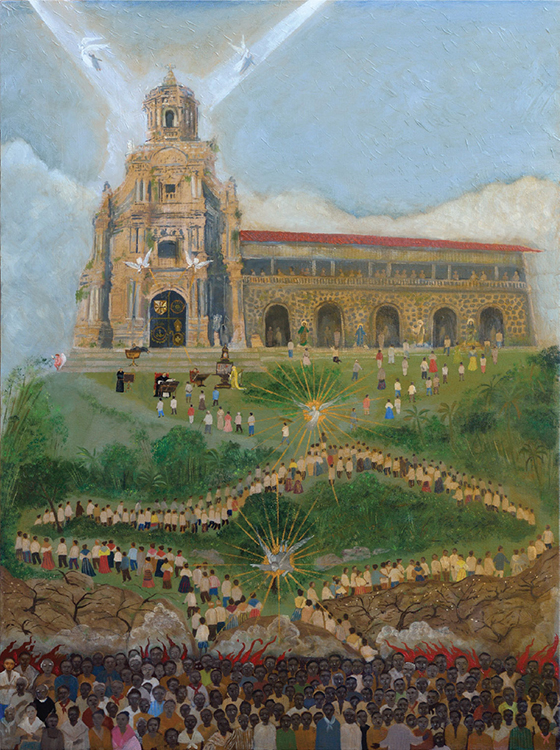

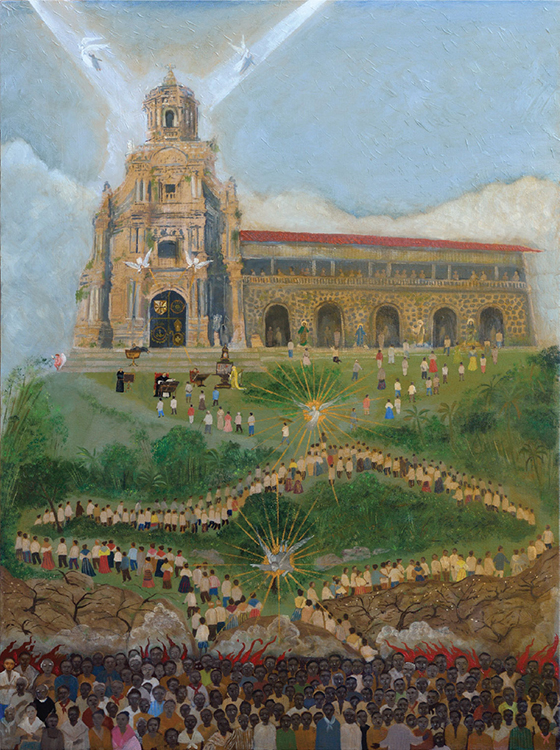

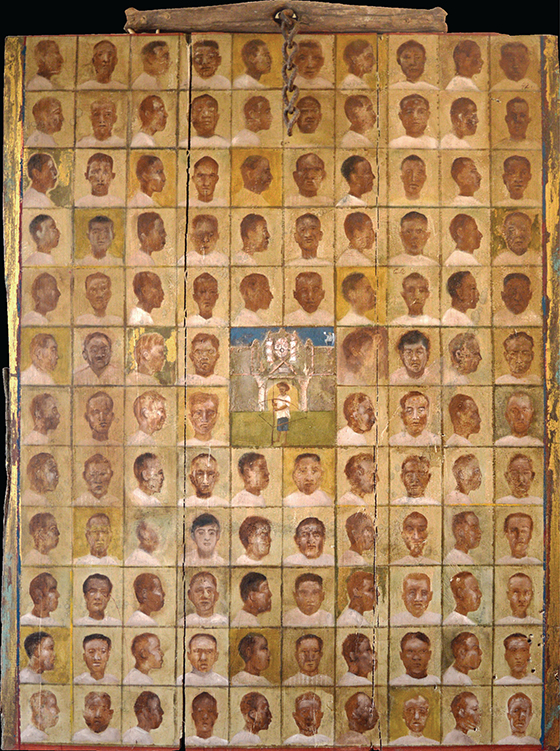

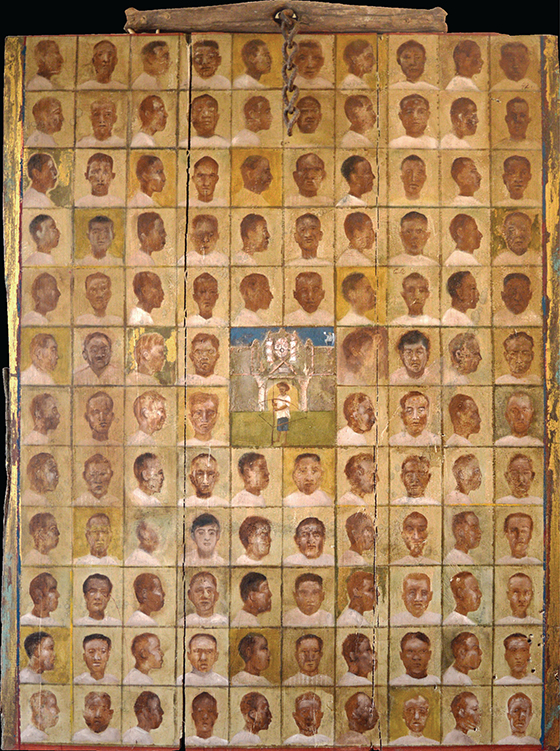

Libro de almas (Book of Souls)

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

The historic church of San Jeronimo in Morong built by the Franciscans in the 17th century represents the gateway to Heaven in this HOCUS painting. Filipino natives are seen milling around the esplanade of this imposing Church; the ecclesiastical symbols of the major religious orders are emblazoned on its portal, each represented by a friar, seated in front, preoccupied with a census dramatically called the Libro de Almas (Book of Souls), containing the names of”enrolled souls’:

Attached to the church is the convent where souls await Final Judgment; there are patron saints standing by its arches, ready to intercede for the faithful indios. There are only four possible destinations- Limbo, Purgatory, the fires of Hell and paradise in Heaven. Angels direct the souls to their final destination; only those who are led to the belfry are flown directly to the Almighty.

Libro de almas

(Book of Souls)

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

Dios esta esperando (God is Waiting)

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

The indio’s sufferings on earth are rewarded by eternal life. Eternal life doing what the doctrine adequately fails to explain. Perhaps he will be rewarded the right to play music for the heavenly Father, as the angels above seem to suggest. The right to pass the gates to Heaven are controlled by the Holy Orders. Although the fences seem inutile and the locked gates useless since the indio could easily surmount the brick fences and cross the checkered board of night and days towards the stairs leading to heaven. But who is the indio to question established dogma?

Dios esta esperando

(God is Waiting)

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

Santiago Matamalayu (St. James, killer of Malays)

Oil on wood, 4 feet x 3 feet

Santiago de Matamoros is supposed to be St. James the Elder, an apostle of Jesus Christ. According to legend, he fought against the Moors in the Battle of Clavijo which historians said never took place. Because of the “Reconquista’: St. James, or Santiago, was venerated as patron saint of Spain until 1760, when the Pope declared the Immaculate Conception the patroness of the Kingdom. Throughout the Spanish Empire, there were forts, towns, government buildings and churches dedicated to Santiago Matamoros. You can imagine how shocked the Spaniards must have felt when they encountered Moros in the far-flung Islas Filipinas after having circumnavigated the world.

The central figure in this HOCUS painting is Santiago Matamoros as he is portrayed in many colonial paintings and moro-moro dramas in the Philippines. He is surrounded with vignettes depicting Christianization-a priest burning a native god and a friar holding up a manuscript written in baybayin script. Indigenous communities in Palawan, Mindoro and Bohol still use a native syllabary up to this day.

Inadvertently perhaps, Santiago was eventually indigenized. In religious colonial paintings, Spain’s former patron is seen killing infidels that look more like indios of this archipelago as illustrated in the Boxer Codex than the Moors of southern Spain. In the Luis Araneta collection, there is a rare ivory piece which shows Santiago slaying a native lady moro. Patron of Spain’s anti-Muslim wars, the warrior-saint could very well be called Santiago Matamalayu, or St. James, killer of Malays, for they are exactly the people he is seen killing, the indigenous denizens of this archipelago.

Santiago Matamalayu

(St. James, killer of Malays)

Oil on wood, 4 feet x 3 feet

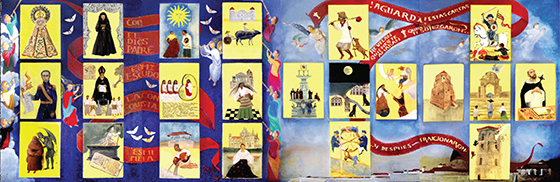

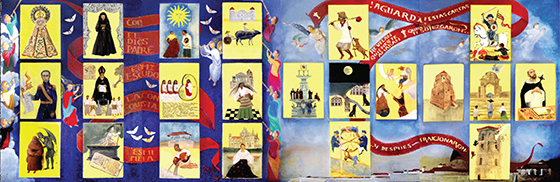

The Cartas Philippinensis Panel

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 12 feet

Shows the Tarot Cards with Philippine themes. These cards speak to us of our past, when the church, in conjunction with the Spanish civil authorities, ruled the lives of the indios.

The Cartas Philippinensis Panel

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 12 feet

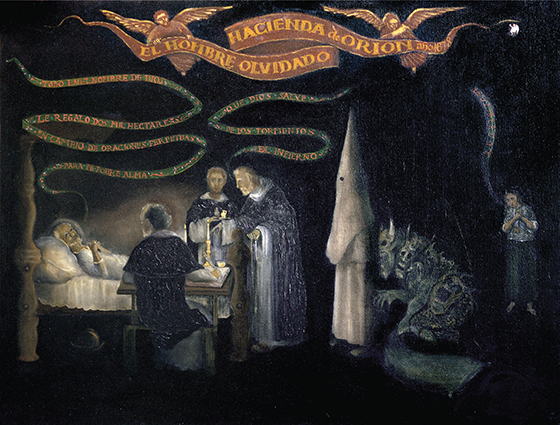

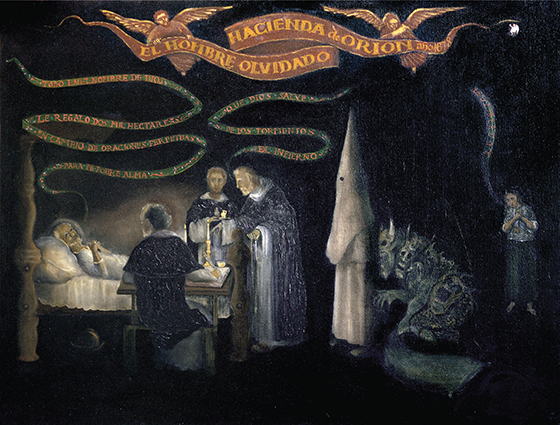

El hombre olvidado (The Forgotten Man)

Oil on canvas, 3 feet x 4 feet

Extensive land donations were obtained by crafty friars with deathbed manners in exchange for Holy Masses celebrated in perpetuity that would guarantee a higher place in Heaven for the generous donor. The dying man in this HOCUS painting, obviously a former conquistador, as shown by a morion helmet under his bed, was the owner of the Hacienda de Orion in Bataan. In 1678, on his deathbed, he bequeathed all of 2000 hectares of his royal land grant to the Dominican Order in exchange for a safe and speedy passage to Heaven.

With his last breath, the moribund former conquistador implores the Dominican friars: “Todo en el nombre de Dios, les regalo dos mil hectareas en cambio de oraciones perpetuas para mi pobre alma” (All in the name of God, I give you 2,000 hectares in exchange for perpetual prayers for my poor soul.) As a friar administers the sacrament of Extreme Unction, a scribe dutifully records the man’s last will and testament.

Another friar consoles him: “Que Dios te salve de los tormentos del Infierno!” (May God save you from the torments of hell!) Keeping watch is a mysterious figure wearing a capirote, the conical hat worn by penitents of Sevilla, Spain during Holy Week.

Evil permeates this death scene; a seven-headed devil appears, representing the Seven Deadly Sins.

In a dark corner of the room, the india servant of the conquistador curses the master who may have wronged her: “Sumama ka na sa kanila” (go with them), her words say, written in ancient tagalog script, obviously alluding to the 7 headed demon.

El hombre olvidado

(The Forgotten Man)

Oil on canvas, 3 feet x 4 feet

Retablo del rey Felipe el Segundo (Altarpiece of King Philip the Second)

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

In this HOCUS painting, Felipe Segundo, after whom the Philippines was named, is enshrined at the pinnacle of the ornate retablo. It may look blasphemous, but it attests to the true role of the Spanish Crown in the Christianization of the natives of these islands.

Beneath Don Felipe, every single niche of the retablo is dedicated to a saint, mindfully selected to touch the heart of the natives. San Isidro Labrador, the patron of agriculture, was introduced by the friars to make the new Faith more attractive to the tillers of the soil. The Franciscans presented San Antonio de Padua as the saint who finds lost things for you; St. Francis of Assisi, the founder of the Order; San Vicente de Ferrer of the Dominican Order, who had the gift of tongues and he is also the patron of builders; and there is San Roque, the patron of the sick.

To foster feminine virtues, Santa Magdalena and Santa Monica, mother of Saint Agustin, were introduced by the friars upon this shores.

Retablo del rey Felipe el Segundo

(Altarpiece of King Philip the Second)

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

Los Filipinos (The Filipinos)

Oil on wood, 4 feet x 3 feet

This is a tableau of Filipinos from the separated islands of Las Islas Filipinas, the islands that Rizal referred to as the Empire of the Friars. These are the people that Rizal loved and the friars subjugated in God’s name. On the center of the painting is an indio doing guard duty for the Spanish Crown-or is he thinking of how to overthrow his Iberian masters?

The noted historian, Milagros Guerrero, said that if you will read the first chapter of Rizal’s El Filibusterismo, you would realize the reason why the friars willed Rizal’s death. It is because Rizal’s genius could awaken his people from centuries of slumber caused by religion.

Los Filipinos (The Filipinos)

Oil on wood, 4 feet x 3 feet

La pesadilla (The Nightmare)

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 11 feet, Triptych

This HOCUS triptych depicts Good and Evil locked in a fierce and perpetual battle for hegemonyover the Earth and its creatures. Take your time to unravel each image, nightmares in my mind, which I have explained to Guy Custodio with a proliferation of details. I see death in various forms: “mga araw na walang Diyos” (days with no God), post-Golgotha and pre-Resurrection. There were demonic times in the country’s history during which Filipinos feared that there was no God.

There is a man, wearing a dunce cap seated by a whirlpool beside a clock whose numbers are reversed, trivializing the letters “historia” (history), mindlessly obscuring the past, a hindrance to preparing for the future. An old woman hurls a crucifix as if it were a grenade at the direction of death marching in a phalanx.

Beside a meandering river, an ancient symbol of life, a monstrous “kapre” plays mournful dirges on a bamboo organ, a fitting background to the thunderous clash between the Forces of Evil and the Army of Good. Shrieking wildly, a demented friar commits sacrilege by riding a dragonfly, which is, to my mind, is the symbol of the crucified Christ. He rides in the popularity of the crucified Son of Man. Another man, wearing the clothes of a member of the principalia, rides a creature that looks like a queen termite with wings. A little

girl crouches in fear in the middle of the painting. The living is seen carrying death standing on top of an open palanquin; a skeleton beating a drum with the symbol of the Christian inquisition, rat-like lemmings are seen running towards the river in an act of collective self-destruction.

Ah, there is a glimmer of hope as an innocent child holding a candle walks towards the Christless cross.

A friar gloats as he indifferently beats a drum. In the background, a church burns symbolizing the destruction of the Faith. Instead of brilliant stars, the three islands-Luzon Visayas and Mindanao-are shown as three skulls at the foot of the empty cross. Has the Savior abandoned us?

Crabs are ubiquitous in the painting reminding us of an evil habit that corrodes everything good in our national character-crab mentality.

On the left panel of the triptych, cimmerian clouds of gigantic bats, which at closer look are tenebrous manananggals, represents the Forces of Evil. To the right, a lady sits before a mirror grooming herself, oblivious to everything.

La pesadilla

(The Nightmare)

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 11 feet, Triptych

Permanent Exhibit, National Museum of Fine Arts, Republic of the Philippines

The Treaty of Tordesillas

Oil on wood, 4 feet x 3 feet

The Treaty that divided the world like an orange is the subject of this painting.

The 15th century treaty was brokered by the Borgia Pope, Alexander the VI. The Treaty established a line of demarcation that neatly divided ownership of the world and its inhabitants between Portugal and Spain.

To the right of Alexander are the Catholic monarchs of Spain, Don Fernando of Aragon and Reyna Isabella of Castile and to his left is the Portuguese king, John.

The divided world is shown in the painting with Spanish and Portuguese angels and indigeneous angels of the conquered territories armed with their native weapons, fighting over the territory divided by the Catholic Pope.

The Treaty of Tordesillas

Oil on wood, 4 feet x 3 feet

The Celestial Chess Players

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

Two celestial chess players are deeply engaged in their game while angels bearing a mirror reflect the crucial position of the pieces on the chessboard.

The angel on the left wears a sash that says “Capitania-General de las Yslas Philipinas” which was how this colony was called. The sash of the other angel reads” Espejod e los angeles”– which means ” mirror of the angels” implying that it reflects only what is true.

Notice the position of the pieces: The black ones represent the indio. The black King’s position is severely restricted by the two Bishops occupying their posts. The Bishops represent ecclesiastical authority. The Rooks are threatening the two helpless black center Pawns. The rooks symbolizes State power.

There are more black pieces, but the fearsome white pieces are threatening mate at every turn. The fact is, the black pieces are powerless, like the indios during the

Spanish colonial period who could never have won this HOCUS chess match simply because the white King, which should be on the chessboard, is absent. How then could black win a game whose object is to capture the King of the opposite color?

The Celestial Chess Players

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

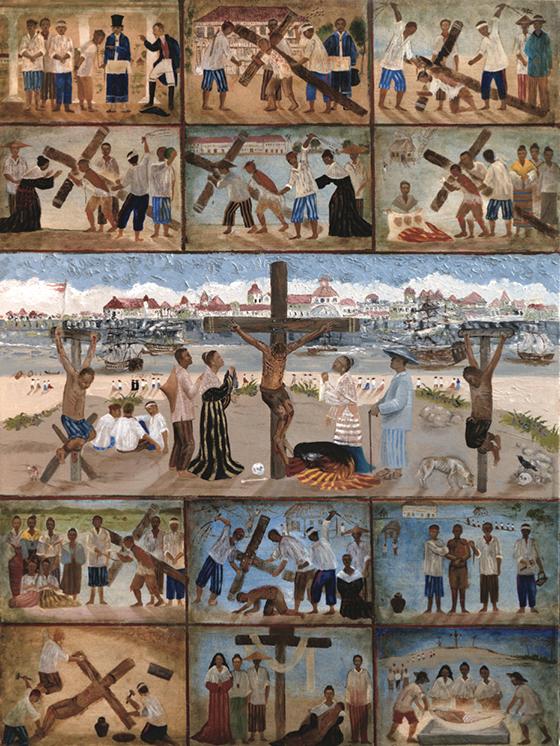

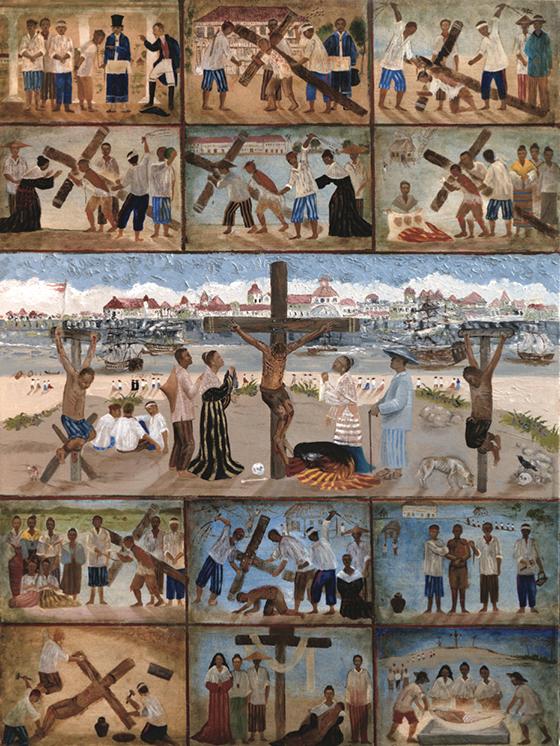

El camino de la cruz en Manila (The Way of the Cross in Manila)

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

Inspired by historian Rey Ileto’s monumental Pasyon and Revolution, this HOCUS painting attempts to show how the Filipino masses translated the Passion and Death of Jesus Christ into their own existence, struggle and redemption during Spanish colonial times. Jesus Christ suffered at the hands of his fellow Jews who scourged Him mercilessly, dragged Him to Calvary where He was crucified on the cross, between two thieves. In the Philippine colonial scene, according to Dr. Ileto, “the pasyon made available a language for venting ill-feelings against oppressive friars, principalia and agents of the State’

To the Christianized masses during the colonial times, the scenes of oppression shown in this HOCUS painting were quite familiar. They identified life in this “valley of tears” with the passion of Christ, His death and glorious resurrection. That is why the Filipino masses seem to be long-suffering, docile and submissive in the face of injustice and oppression, the Savior will come someday and take them with Him to Paradise.

El camino de la cruz en Manila

(The Way of the Cross in Manila)

Oil on canvas, 4 feet x 3 feet

Simbolos del poder (Symbols of Power)

Oil on wood, 5 feet x 4 feet

The painting speaks of the symbols of Spanish power.

The quarters of the Spanish escudo shows the more important churches in the Philippines as well as a floor plan of a Spanish church. The Spanish shield superimposes Intramuros-the Walled City which was used by the Spaniards as their bailiwick during the colonial period.

The churches of Panay, Zambales, Nueva Vizcaya, Cuyo, Misamis Occidental, Tuguegarao, Isabela, Cagayan, Paoay and Romblon also emblazon the schematics of Intramuros, emphasizing the control of the State in the propagation of the Faith. Words from the law reserving a portion of the income of the State towards the building of churches are quoted on the left corner of the painting.

The indio, who was caught between the powers of Church and State, the twin powers that exercised control over his soul and daily existence, did not have a Chinaman’s chance against the joint enterprise.

Simbolos del poder

(Symbols of Power)

Oil on wood, 5 feet x 4 feet